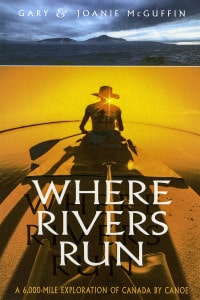

SIMPLY SUPERIOR

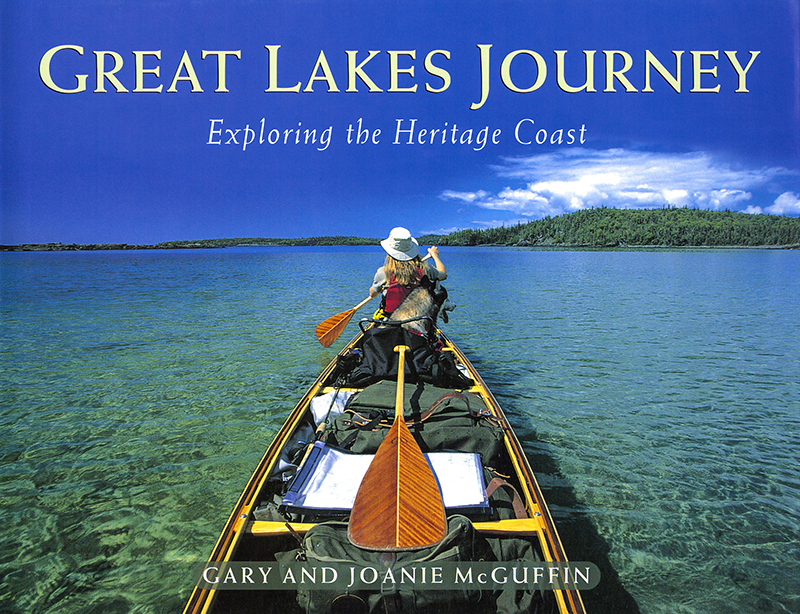

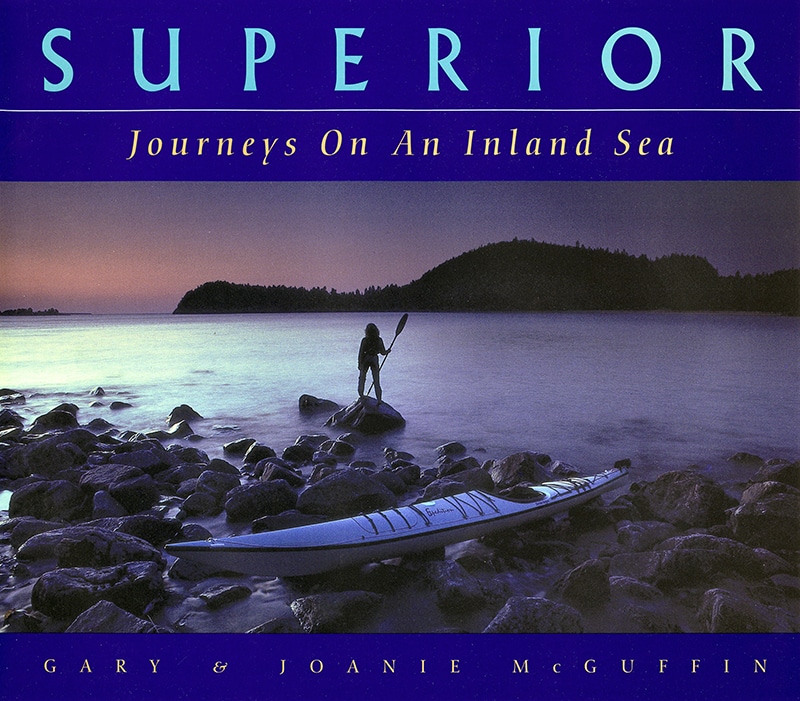

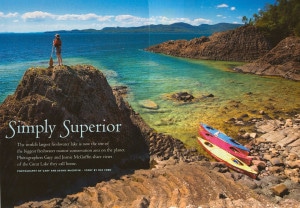

The world’s largest freshwater lake is now the site of the biggest freshwater marine conservation area on the planet. Photographers Gary and Joanie McGuffin share views of the Great Lake they call home.

By Ray Ford

Article in Canadian Geographic, June 2008

As the sunrise streaked Lake Superior’s islands with shadows and light, Gary McGuffin noticed an oddly familiar shape near his campsite: an ancient spear point, so close he could have stepped on it.

As the sunrise streaked Lake Superior’s islands with shadows and light, Gary McGuffin noticed an oddly familiar shape near his campsite: an ancient spear point, so close he could have stepped on it.

“I imagined the person who sat there, maybe hoping the spear would bring an animal that day.” Says McGuffin, recalling his find during a 17-day paddle of north-central Superior with a group of artists last summer. “I wondered what we can do to see that this experience remains the same for future generations.”

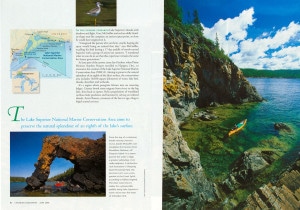

At least part of the answer came last October, when Prime Minister Stephen Harper travelled to Nipigon, Ont., to announce the creation of the Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area (NMCA). Aiming to preserve the natural splendour of an eighth of the lake’s surface, the conservation area includes 10,850 square kilometres of water, lake bed, islands, shoreline and wetlands.

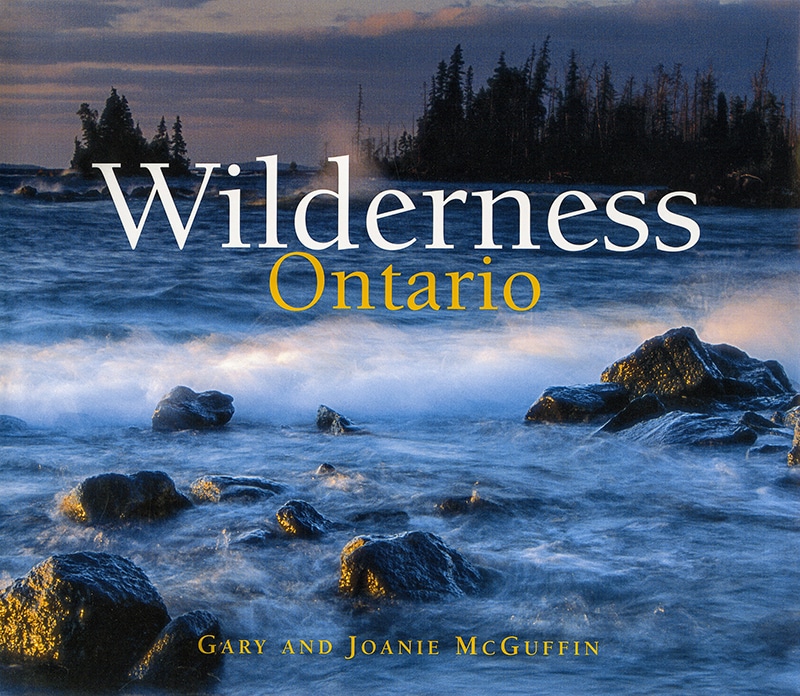

It’s a region where peregrine falcons nest on towering ledges. Coaster brook trout migrate from rivers to the big lake, then back to spawn. Relict populations of woodland caribou elude predators and humans by calving on isolated islands. Arctic flowers, remnants of the last ice age, cling to frigid coastal crevices.

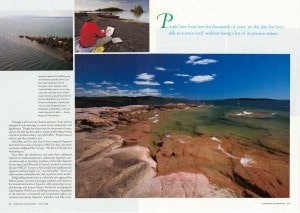

Through it all is woven a human presence, from ancient aboriginal rock paintings to more recent shipwrecks and lighthouses. “People have been here for thousands of years, and yet the lake has been able to sustain itself without losing a lot of its pristine nature,” says McGuffin. “People interact with it, and they cherish it too.”

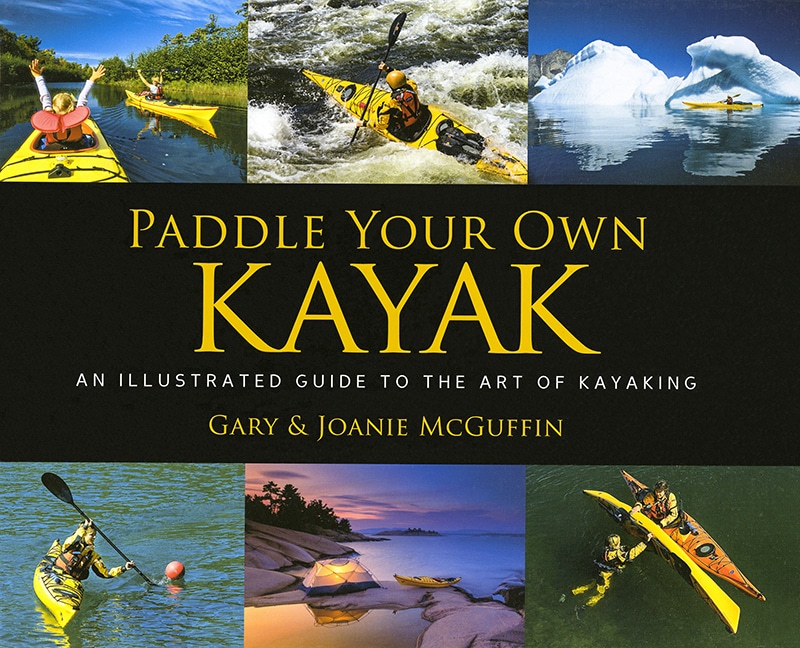

McGuffin and his wife Joanie have treasured Superior since their first canoe crossing in 1983. For days, the water was nearly “millpond-flat,” he says. “We felt as if the lake was welcoming us.”

Since then, the adventurers and artists have celebrated Superior in words and pictures, settled near Superiors eastern shore and, as founding members of the Lake Superior Conservancy and Watershed Council, worked to promote the new NMCA. “I want to show people how significant this region is and how fragile it is,” says McGuffin. “There’s no other section of shoreline like this anywhere in the world.” Safeguarding marine areas is relatively new approach by Parks Canada, one that encourages residents and visitors to live around and work on Superior, while protecting its natural heritage and human history. Details for managing the Lake Superior NMCA are still being worked out. Regardless of the outcome, commercial and recreational anglers can continue harvesting Superior’s whitefish and lake trout, Kayakers can explore islands and shorelines and private property remains unaffected. But prospecting, mining, oil and gas development and waste dumping are off limits within the NMCA.

Since then, the adventurers and artists have celebrated Superior in words and pictures, settled near Superiors eastern shore and, as founding members of the Lake Superior Conservancy and Watershed Council, worked to promote the new NMCA. “I want to show people how significant this region is and how fragile it is,” says McGuffin. “There’s no other section of shoreline like this anywhere in the world.” Safeguarding marine areas is relatively new approach by Parks Canada, one that encourages residents and visitors to live around and work on Superior, while protecting its natural heritage and human history. Details for managing the Lake Superior NMCA are still being worked out. Regardless of the outcome, commercial and recreational anglers can continue harvesting Superior’s whitefish and lake trout, Kayakers can explore islands and shorelines and private property remains unaffected. But prospecting, mining, oil and gas development and waste dumping are off limits within the NMCA.

Economic benefits include the $36 million Parks Canada has budgeted to establish and operate the conservation area over the next 10 years. Tourism could have a bigger impact on the economy, but the challenge is to ensure the region is appreciated without being loved to death.

The NMCA’s greatest value may be the stewardship it encourages. In the months before Harper’s announcement, Trout Unlimited Canada, an organization dedicated to the conservation of freshwater fish, purchased a 24-hectare property, with the support of the Nature Conservancy of Canada, governments and private donors, to protect Gapen’s Pool, a prime spawning site for coaster brook trout at the conservation area’s northern boundary.

Groups such as the Lake Superior Conservancy and Watershed Council hope individual landowners will play a role too. Residents “have a strong sense of connection with the area,” says executive director Brian Christie. “They see protecting it as a part of their legacy.”

Yet Superior’s future isn’t solely in the hands of residents and visitors. Like other lakes, it is facing the effects of a warming climate and accumulating airborne toxins. Last September, Superior reached its record low level, 10 centimetres below the previous low point, recorded in 1926. (Heavy autumn rains helped levels rebound, but the lake is still well below normal.)

Yet Superior’s future isn’t solely in the hands of residents and visitors. Like other lakes, it is facing the effects of a warming climate and accumulating airborne toxins. Last September, Superior reached its record low level, 10 centimetres below the previous low point, recorded in 1926. (Heavy autumn rains helped levels rebound, but the lake is still well below normal.)

Drought is the immediate cause, but University of Minnesota researchers Jay Austin and Steve Colman suspect it is part of a larger trend linked to global warming. Analyzing data from Superior’s weather buoys, they have discovered the lake’s waters are warming twice as fast as the air around it. Warmer water means less ice, and stronger winds speed evaporation. If the trend continues, Superior could be regularly ice-free during the winter within 30 years. While the new NMCA works to preserve the essence of Lake Superior’s imposing north shore, climate change means the lake that seems so vast and powerful is, like the Artic flowers it shelters, increasingly fragile.

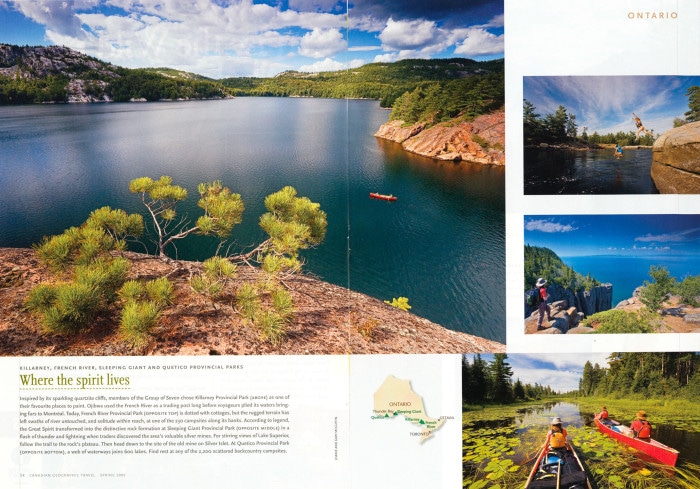

Where The Spirit Lives

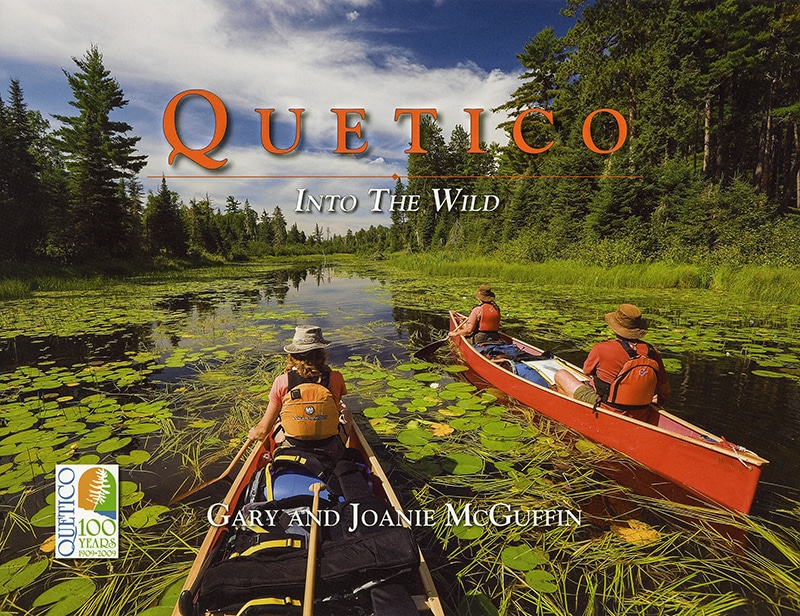

Killarney, French River, Sleeping Giant and Quetico Provincial Park

Photos By Joanie and Gary McGuffin

Article in Canadian Geographic Travel, Spring 2009

Inspired by its sparkling quartzite cliffs, members of the Group of Seven chose Killarney Provincial Park (Above) as one of their favourite places to paint. Ojibwa used the French River as a trading post long before voyageurs plied its waters bringing furs to Montreal. Today, French River Provincial Park (Opposite Top) is dotted with cottages, but the rugged terrain has left swaths of river untouched, and solitude within reach, at one of the 230 campsites along its banks. According to legend, the Great Spirit transformed into the distinctive rock formation at Sleeping Giant Provincial Park (Opposite Middle) in a flash of thunder and lightning when traders discovered the area’s valuable silver mines. For stirring views of Lake Superior, follow the trail to the rock’s plateau. Then head down to the site of the old mine on Silver Islet. At Quetico Provincial Park (Opposite Bottom), a web of waterways joins 600 lakes. Find rest at any of the 2,200 scattered backcountry campsites.