Circle of Rivers

NorthernHoot.com, April 20, 2015

We all store flat maps in our minds of the places we know, the places we’ve been and the places we live. Roadmaps are the most familiar, but then there are the topographic maps that describe contours in 50-foot intervals and waterways in threads and puddles of blue. These maps ignite journey dreams as we picture the landscape and see ourselves following these original highways for weeks, sometimes months, on end. Journeys turn maps into 3-dimensional realities of place and time. The physical exertion of self-propelled travel combined with our sharpened sense creates indelible memories by experience.

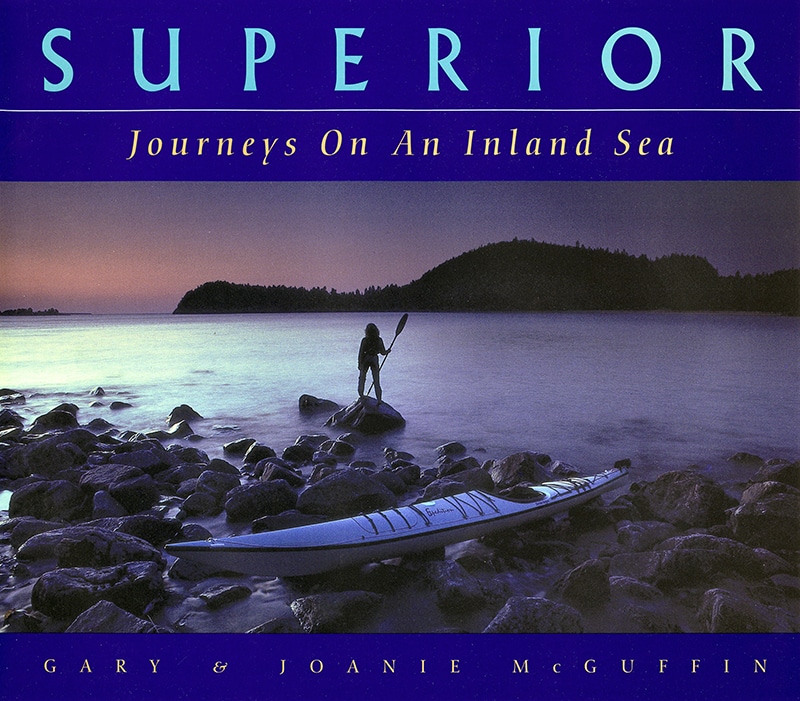

Take the Map of North America, zero-in toward the centre, and you will find the Great Lakes. At the top of these lakes is the largest expanse of freshwater on earth, aptly named Lake Superior. This inland freshwater sea is the hub at the centre of river spokes, waterways that form a myriad of ways to reach the four oceans surrounding the continent.

One morning, in the middle of a five- month bicycle traverse of Canada, we rested at a spectacular lookout over Lake Superior’s Nipigon Bay islands.

Gary spread our map out on a flat rock. He pulled a string from his pocket and anchored one end where we stood now and proceeded to kink the string in and around all the nooks and crannies of the lake’s bays until the circle was complete. He cut the string at this point, sealed its end to prevent fraying and handed it to me. The string and the folded map became a dream to fulfill. I tucked them carefully into my trip diary. We climbed back on our bicycles and headed east for two more months.

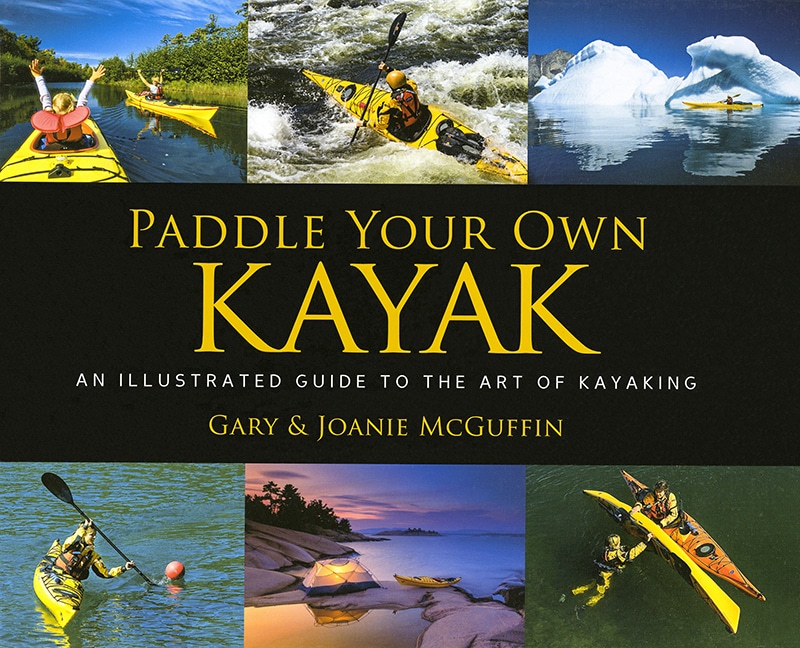

Two years later, we set off on our three month circumnavigation around Lake Superior’s 2,000-mile shoreline. Planning the route was simple.

Begin where the dream was born, on the lake’s most northerly point, Kama Bay, and circle the lake according to its own natural, counterclockwise currents. We would paddle in solo sea canoes letting Superior dictate the schedule of our days.

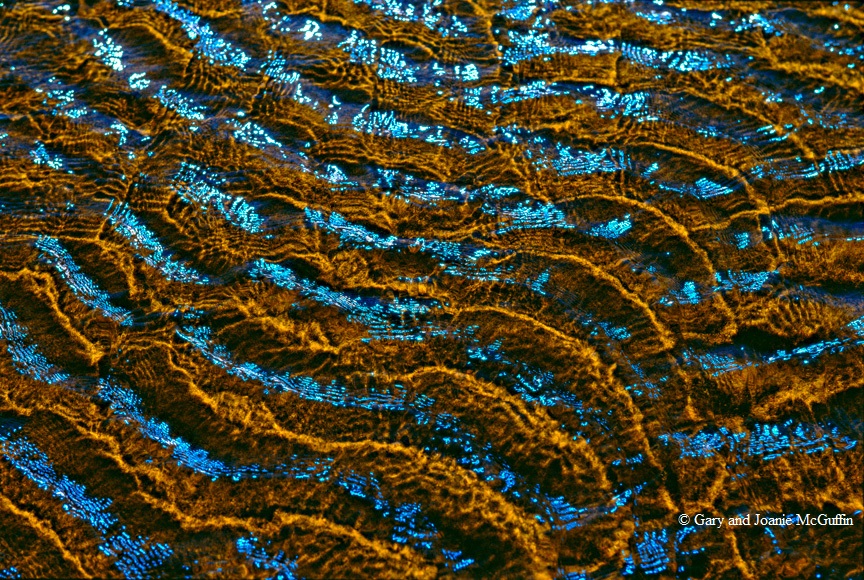

A half-day’s paddle from Kama Bay brought us to the mouth of Lake Superior’s largest tributary, the Nipigon River. A fine sand brought south by this river from Lake Nipigon hangs in suspension behind the screen of north shore islands colouring the waters an opaque turquoise green. On the east side of the Nipigon river mouth, where a rock wall drops straight into the lake, twisted, gnarled cedars grow from cracks and crevices.

Nearby, a small frog swam listlessly. I scooped it up and placed it on a warm ledge of rock to recuperate. It was the first of many small creatures- from bumblebees to butterflies- that I rescued from Superior’s frigid waters over the course of the summer.

Suddenly we were aware of straight lines and arches painted on the rocks above. Long ago this ochre had been bonded to the rock with natural oils. Over time, dissolved minerals seeping down the cliff varnished and preserved them. We interpreted the paintings as people, canoes and caribou.

Most intriguing was the little frog-like man with arms and legs outstretched in a dance across the rock. Maymaygwaysiwuk, we whispered, thinking of the bewhiskered little men who paddled stone canoes, stole fish from nets and followed tunnel channels between Lake Nipigon and Superior. These are touchstones with those of our own species who were aware of many things we no longer perceive.

Early on, our voyage around Superior’s lakeshore became a discovery of its watershed. Each day we passed river mouths, some being small creeks, others more major rivers. We paddled through the north shore islands from St. Ignace to the Black Bay Peninsula, discovering flowing currents right within the lake itself. These seiches are Superior’s tides caused not by the moon’s gravitational pull, but rather by the ‘sloshing’ of water back and forth across the lake’s enormous surface.

Sometimes we camped on the islands, but more often we set up camp by the mouths of mainland rivers. Waters of various hues flowed over flat rock and sand before emptying into the deep cold lake. At every campsite we noticed how each river made a different sound, the rush of one, the burble of another. Some creeks we could hear but not see as they tumbled through thick cedar forests before foaming out into the lake. On quiet evenings the cedar waxwings caught insects on the wing. Their soft twittering echoed the bubbling of river mouth foam. Perhaps the people who camped here long, long ago named these rivers by way of their sounds just as they named hills by their shape and colour.

Beneath the great hulking landform of the Sleeping Giant, we paddled toward the little hamlet of Silver Islet. The silver mining shafts located near an offshore island, are no more than two dark eyes staring up from underwater. Long ago they flooded, losing the battle with the Lake’s November storms. We climbed to the top of the sheer bluffs of the Sleeping Giant’s feet and gazed 800 feet below to the gray-green combers rolling in toward Pie Island and Thunder Bay. On top of the peninsula, we found jasper taconite tooled into weapons for hunting caribou 11,000 years ago.

We investigate each bay, large and small. Sometimes we paddled from dawn to dark, taking advantage of fine, calm weather. We traversed Thunder Bay at Caribou Island, the smell of gulls reaching us long before the birds. Then a blizzard of wings arose from the rock and windswept nests. Swirling and diving, they appeared to us as pink kites in the sunset’s afterglow.

Thunder Bay, the city, was a sharp contrast to the wildness of the lake we had been traveling. Instead of the forest to our right, it was now an avenue of commerce complete with the railway, granaries, harbours and ships. We paddled into the city by way of the Kaministiquia River to visit the re-created fur-trading post called Old Fort William. For 25 years the Northwest Company maintained a fur-trading rendezvous in the early 1800’s. Now, costumed voyageurs and traders breathe life, albeit somewhat romanticized, into the French voyageurs who paddled from Montreal with trade goods and supplies to exchange with those coming from Northwestern Canada with a rich supply of furs.

Paddling south from Thunder Bay with the ocean of freshwater always to our left side, we were heading south. Knowing the whereabouts of the Pigeon River was significant for the practical purpose of making an international border crossing from Canada to the United States. Producing citizenship at a river mouth reminded us of the artificial nature of political boundaries. Man-made divisions of provinces, states and countries are irrelevant to the natural flow of water. It courses through our bodies, from the Great Lakes to the sea, from the clouds through the forests and into the deepest reaches of Superior itself.

Our route southwest along the Minnesota shoreline of Lake Superior was almost arrow-straight. Sparsely scattered islands and only a light peppering of shoals provided refuge from winds on the stretches where we could not get ashore. A gull perching on the cliff at Palisade Head reminded us of our vulnerability to the lake’s temperamental winds. We scanned the horizon often searching for the stripe of deep blue telling of approaching winds.

The Manitou, Cascade, Temperance and Split Rock are among a handful of exquisite wild rivers pouring from the glacial scoured Sawtooth Mountains. The volcanic rock of this magic world is full of caves and archways that sometimes lead into the quiet bays where rivers tumble straight into the lake warming the water for swimming.

At the Duluth Harbor, we turn east where the St. Louis River flows in from the southwest. We picture yet another avenue to the oceans. Resting on the long sand spit of Minnesota Point, we contemplate our map. Paddle and portage up the gorges of the St. Louis River and we could reach the Mississippi and paddle all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. The thought was satisfying. That feeling of turning a corner, following a river, just paddling on and on is a universal sentiment echoed in some of the early journals of fur traders, map makers and missionaries. But the people we think about even more came long before. They were the traders of copper, obsidian and pearl who paddled canoes great distances between the peoples of a continent thousands of years ago. River routes were as unending as the flow of water. Even on our journey around Superior, paddling past the river mouths of several different rivers a day, we were appreciating them as more than single threads with put-in and take-out points.

Reverberating deep within the recesses of a cave came the belch and grumble of waves. We followed the sound, enjoying the play of light off the green waters on the passageways of red sandstone. In the Apostle Islands off the Bayfield Peninsula, the geology is different from anywhere else on the lake. We imagined Superior as having a giant tongue that shaped the soft rock in the way we lick ice-cream cones. Two days later we were through the islands heading for the Bad River leaving the brief signature of our passing – two tiny silver wakes on an ocean of freshwater.

While pitching our tent between the East and West Sleeping Bay Rivers we watched a pair of bald eagles circling and swooping low over a huge white pine. The thick limbs supported an enormous nest and beside it perched the eagle pair’s full-grown offspring. Over the lake, a storm was brewing. Cumulous clouds thundered towards us like buffalo across the open plain of blue-black waters. The darkening sky swallowed a squashed red sun in the west, while lightning darts jabbed the horizon to the east. Two storms were converging on us. The eaglet did not move. It was as much a part of this storm as the drift logs and the stones. Waves slapped the shore as steady and insistent as a pow wow drum beat. Although only a few big drops struck us as the storm galloped past, the deluge over the Porcupine Mountains reached us the next day by way of rising rivers.

So many rivers with each a different character: The Brule, a lovely river trip in the southwestern part of Superior, the Ontonagon where the Chippewa once harvested sturgeon in great numbers, the whitewater Montreal dividing Wisconsin and Michigan. The shipping channel across the Keweenaw Peninsula had the feel of a river, although it is not. During one of Superior’s windy weeks, this channel gave us a rest from the concerns of big lake travel. Tail winds filled the strong golf umbrellas we carried. We held them out in front of us and traveled for miles past the reminders of this region’s copper history; the black stamp sand beaches of Freda and the crumbling copper mills at Houghton and Hancock.

Eastward from the Huron Mountains we discovered The Grand Sable Dunes near Grand Marais. The result of a huge crevasse in the glacial ice that, after melting, left a 300-foot high river of sand curving along Lake Superior shore. We discovered rivers like the Two-Hearted by simply walking inland a short distance. The Two-Hearted flows eastward paralleling the lakeshore for two miles before cutting through the beach and spilling into Superior.

The picture we held in our heads of Lake Superior, up until Whitefish Bay, was of a basin into which all rivers flowed. But then we saw the Whitefish Rapids of the St. Mary’s flowing out of Lake Superior and thought of the lake as a great big pool in the middle of a much longer river system flowing to the sea. The St. Marys’ River has the distinction of being the only natural outflow from Earth’s greatest expanse of freshwater. Because Lake Superior is so deep, it takes 250 years to completely replace the water system in the lake. So, as we meet the rivers flowing into Superior, we are meeting the waters that can stay in Lake Superior for 10 generations. A special map of Superior’s lake currents was given to us before our journey. We thought often of this counterclockwise flow because we followed it. Just like a river, it forms huge eddies in the huge bays of the lake. Just north of Whitefish Bay the currents encircle a small island called Caribou, near the place where the infamous iron ore ship the Edmund Fitzgerald sank in a November gale.

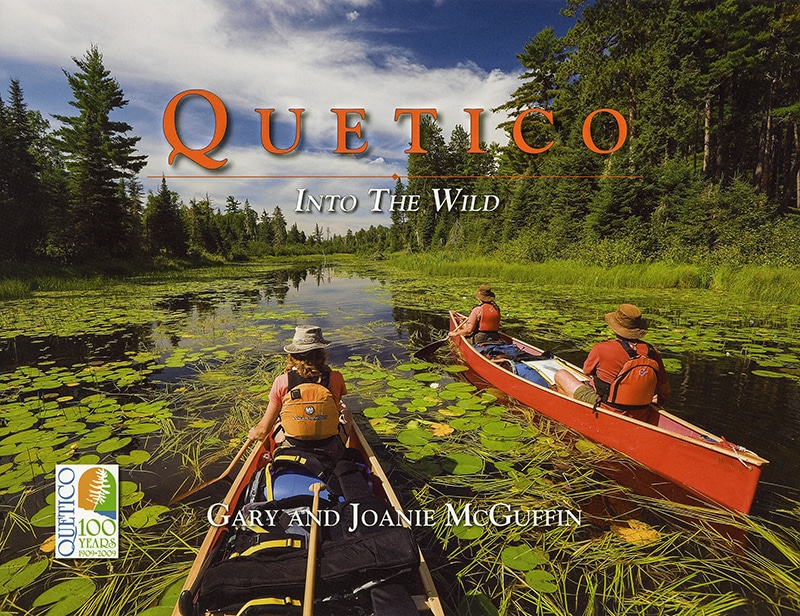

The two deep bays laying north of Whitefish Bay on Superior’s east shore are Goulais and Batchewana. The large rivers flowing into them are similarly named. They, along with the Chippewa, Montreal and Aubinadong, flow from a rare and special top-of-the watershed ancient forest. The Algoma Highlands east of Lake Superior is one of the finest pieces of Great Lakes-St. Lawrence forest remaining on the map of North America today. The rivers flowing from the heart of this forest fed from the wetlands, springs and small lakes carve avenues through old-growth red and white pine forests.

We watched an up-bound, ocean-going freighter pass en route to Thunder Bay, Duluth or Marquette and a down-bound freighter heading south for lower Great Lakes. We not only knew their destination, but we knew what lay in between. Far out beyond the horizon is a shore we have paddled on this same journey, on this same lake. With darkness, the distance grows upwards as well as outwards across the watery expanse.

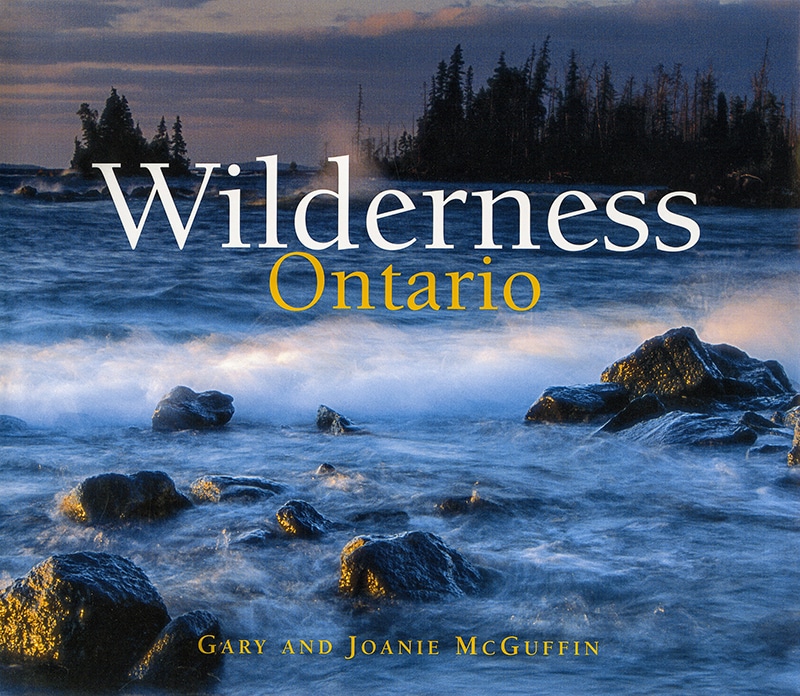

Spectacular beaches at the mouth of the Sand and Agawa Rivers sweep north with the natural counterclockwise flow of lake currents. Sculpted by ice and high water, both river mouths are constantly evolving. The Sand’s original name is the Pinguisibi meaning “river of fine white sand”. The shoreline here is part of Lake Superior Provincial Park, boreal scenery with a fringe of arctic landscape at the lakeshore.

A great sweep of sand beach reaches south from the Michipicoten River. We camped here after a long day’s paddle from Old Woman Bay and Bushy Bay. The next morning we bucked the wind-piled waves against the out-flowing river and managed to get within the safety of the river mouth. This was often the way on Superior. The river mouths could be treacherous if it was shallow and the wind blew onshore.

The Michipicoten was another familiar gateway, one that had taken us to the saltwater of James Bay via the Missinaibi River on our first canoe trip together. This route connected a Hudson Bay fur trade post with Hudson’s Bay. It was the longest running fur trade post out of Lake Superior. For over 40 years, trade happened between the post via the Michipicoten and Missinaibi Rivers. All signs of the post, save for a few grave markers on the hill, have disappeared.

A scalloped shoreline leads us westwards from Michipicoten Bay lighthouse past Point Isacore and on toward the Pukaskwa coast. Dozens of beautiful rivers, coves, beaches and cobble shorelines exist along this section of Superior. Fifteen miles from Michipicoten, we left Superior and paddled up the Dog River in search of Denison Falls. We found the trail, but decided to paddle and pole upstream instead. Near the base of the falls we left the canoes and hiked in. We discovered a rugged portage around the falls that requires a paddler to lower their canoe on a rope down a rock face. This portage begins at a benign looking bend in the upper river. It is a portage you don’t want to miss. From shore, we followed the river’s path as it turned sharply right then dropped over a ledge. We imagined a canoe surviving this and proceeding upright down the alley of rock walls. At the next bend, the rock walls end and the river plunges over the lip of an incredible falls. We paddled the stretch of river from the base of the falls back out to the lake, glad that we had made the effort to paddle upstream earlier that day.

Lying between the Pukaskwa River to the south and east, and the Pic River to the north and west, is Pukaskwa National Park, a 48-mile-long stretch of Lake Superior shoreline with ancient rock headlands and rivers that come cascading down, often sneaking unnoticed into Superior. A massive fissure along a fault valley where the earth’s crust split formed the Pukaskwa River, the park’s southeast boundary. We paddled in from the lake and fished for trout at the base of the falls. Following the tracks of wolf and moose, the Cascade River provided a day’s hike inland.

Finding ourselves windbound here for a couple of days, we took the chance to explore the coast and the Pukaskwa pits. Speculation as to who made these impressions in the cobble beaches, and why, is best contemplated in one’s personal search for them. They vary in size and shape and placement, giving rise to explanations of purpose ranging from hunting, food storage, shelter and vision-questing sites. At Oiseau Bay, we followed fresh black bear tracks around the shore to the river mouth. A plain of sand with trees anchored on strangled angles was an intriguing mystery to solve. We hiked upstream a long way following what appeared as a recent and catastrophic flood. We later learned that a beaver dam had burst and the resultant deluge washed the banks down a great depth leaving an intriguing cross section of sediments, a sandwich of history. For days, trees bobbed around in Oiseau Bay. One brief episode of water on the move changed the direction of this river mouth.

On our last day from Rossport to Kama Bay, we marked off the miles between river mouths; the Gravel and the Jack Pine being two of the last. A circle of string had become the thread of a real journey through the seasons.

In a 60-year-old wooden pencil box marked with my mother’s initials ‘J.M.’, I keep the piece of string and the map that became a journey. Pressed flowers from the Sturgeon River’s wild banks, a bluejay feather from Rainbow Falls, and various rocks including pieces of red sandstone, quartz, taconite, gneiss, slate and more were all collected from the mouths of Lake Superior’s rivers. These various treasures are magic keys that unlock memories that, in turn, become dreams for new journeys.