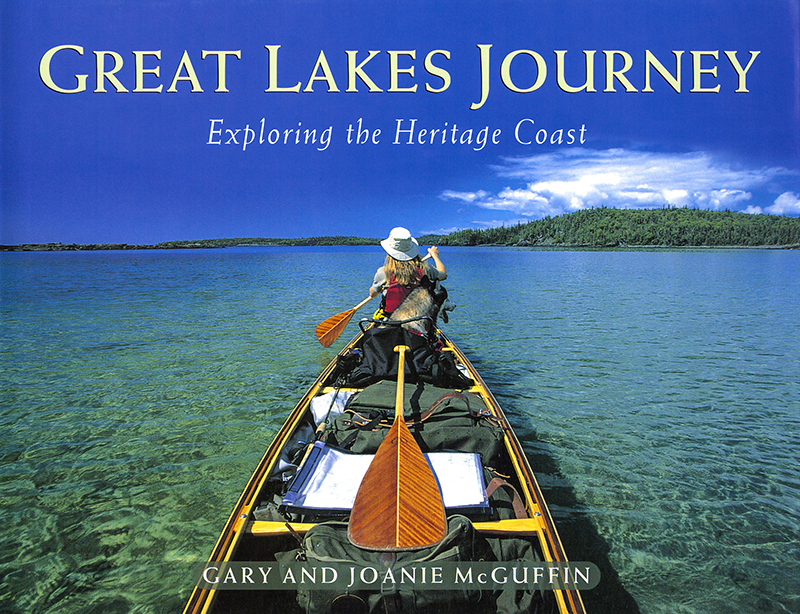

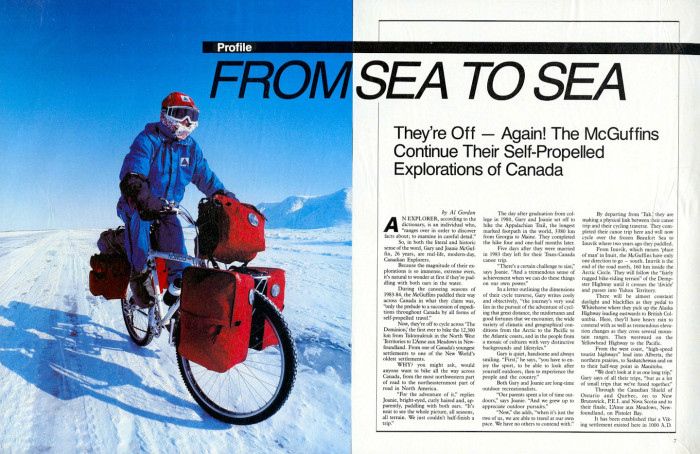

From Sea to Sea

They’re Off – Again! The McGuffins Continue Their Self-Propelled Exploration of Canada

By Al Gordon

Article in Explore

An explorer, according to the dictionary, is an individual who, “ranges over in order to discover facts about; to examine in careful detail.”

An explorer, according to the dictionary, is an individual who, “ranges over in order to discover facts about; to examine in careful detail.”

So, in both the literal and historic sense of the word, Gary and Joanie McGuffin, 26 years, are real-life, modern-day, Canadian Explorers.

Because the magnitude of their explorations is so immense, extreme even, it’s natural to wonder at first if they’re paddling with both oars in the water.

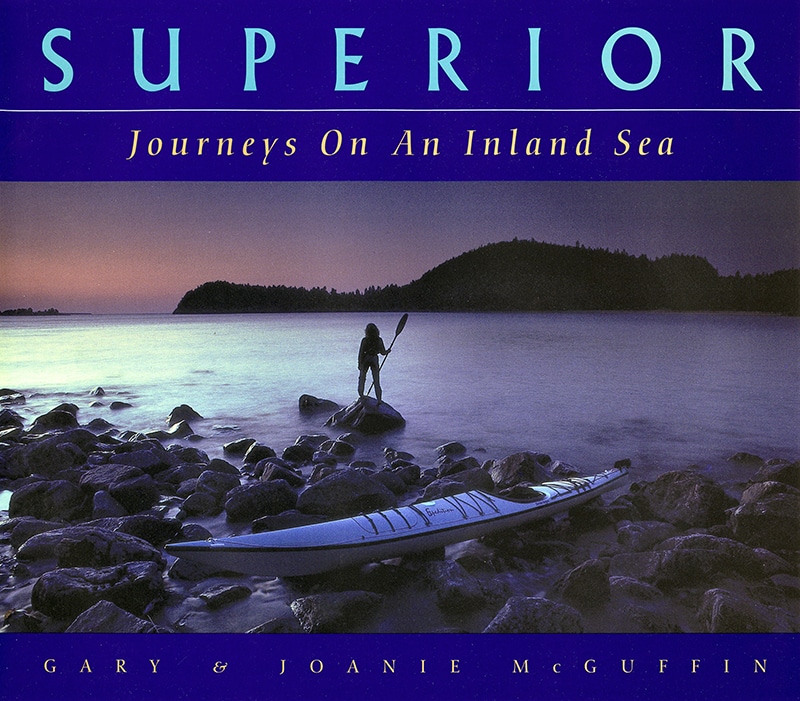

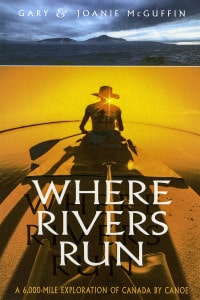

During the canoeing seasons of 1983-84, the McGuffins paddled their way across Canada in what they claim was, “only the prelude to a succession of expeditions throughout Canada by all forms of self-propelled travel.”

Now, they’re off to cycle across “The Dominion,” the first ever to bike the 12,300 km from Tuktoyaktuk in the North West Territories to L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. From one of Canada’s youngest settlements to one of the New World’s oldest settlements.

WHY? You might ask, would anyone want to bike all the way across Canada, from the most northwestern part of road to the northeastern most part of road in North America.

“For the adventure of it,” replies Joanie, bright-eyed, curly haired and, apparently, paddling with both oars. “It’s neat to see the whole picture, all seasons, all terrain. We just couldn’t half-finish a trip.”

The day after graduation from college in 1980, Gary and Joanie set off to hike the Appalachian Trail, the longest marked footpath in the world, 3380 km from Georgia to Maine. They completed the hike four and one-half months later. Five days after they were married in 1983 they left for their Trans-Canada canoe trip.

“There’s a certain challenge to size,” says Joanie. “And a tremendous sense of achievement when we can do these things on our own power.”

In a letter outlining the dimensions of their cycle traverse, Gary writes coolly and objectively, “the journey’s very soul lies in the pursuit of the adventure of cycling that great distance, the misfortunes and good fortunes that we encounter, the wide variety of climatic and geographical conditions from the Arctic to the Pacific to the Atlantic coasts, and in the people from a mosaic of cultures with very distinctive backgrounds and lifestyles.”

Gary is quiet, handsome and always smiling. “First,” he says, “you have to enjoy the sport, to be able to look after yourself outdoors, then to experience the people and the country.”

Both Gary and Joanie are long-time outdoor recreationalists.

“Our parents spent a lot of time outdoors,” says Joanie. “And we grew up to appreciate outdoor pursuits.”

“Now,” she adds, “when it’s just the two of us, we are able to travel at our own pace. We have no others to contend with.”

By departing from ‘Tuk’ they are making a physical link between their canoe trip and the cycling traverse. They completed their canoe trip here and will now cycle over the frozen Beaufort Sea to Inuvik where two years ago they paddled.

From Inuvik, which means ‘place of man’ in Inuit, the McGuffins have only one direction to go – south, Inuvik is the end of the road north, 160 km inside the Arctic Circle. They will follow the “fairly rugged bike-riding terrain” of the Dempster Highway until it crosses the ‘divide’ and passes into Yukon Territory.

There will be almost constant daylight and blackflies as they pedal to Whitehorse where they pick up the Alaska Highway leading eastwards to British Columbia. Here, they’ll have heavy rain to contend with as well as tremendous elevation changes as they cross several mountain ranges. Then westward on the Yellowhead Highway to the Pacific.

From the west coast, “high-speed tourist highways” lead into Alberta, the northern prairies, to Saskatchewan and on to their half-way point in Manitoba.

“We don’t look at it as one long trip,” Gary says of all their trips, “but as a lot of small trips that we’ve fused together.”

Through the Canadian Shield of Ontario and Quebec, on the New Brunswick, P.E.I., and Nova Scotia and to their finale, L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, on Pistolet Bay.

It has been established that a Viking settlement existed here in 1000 A.D. …

Ice Road from Tuktoyaktuk to Inuvik

Article in Explore

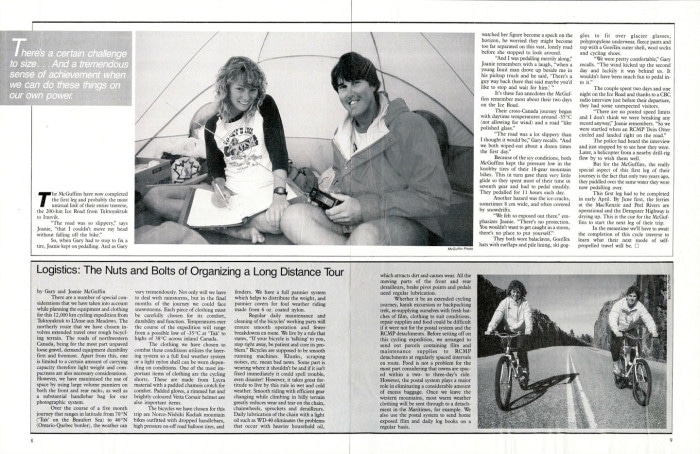

The McGuffins have now completed the first leg and probably the most unusual link of their entire traverse, the 200-km Ice Road from Tuktoyaktuk to Inuvik.

The McGuffins have now completed the first leg and probably the most unusual link of their entire traverse, the 200-km Ice Road from Tuktoyaktuk to Inuvik.

“The road was so slippery,” says Joanie, “that I couldn’t move my head without falling off the bike.”

So when Gary had to stop to fix a tire, Joanie kept on pedalling. And as Gary watched her figure become a speck on the horizon, he worried they might become too far separated on this vast, lonely road before she stopped to look around.

“And I was pedalling merrily along,” Joanie remembers with a laugh, “when a young Inuit man drove up beside me in his pickup truck and he said, “There’s a guy way back there that said maybe you’d like to stop and wait for him.”

It’s these fun anecdotes the McGuffins remember most about their two days on the Ice Road.

Their cross-Canada journey began with daytime temperatures around -35 degree Celsius (not allowing for wind) and a road “like polished glass.”

“The road was a lot slippery than I thought it would be,” Gary recalls. “And we both wiped-out about a dozen times the first day.”

Because of the icy conditions, both McGuffins kept the pressure low in the knobby tires of their 18-gear mountain bikes. This in turn gave them very little glide so they spent most of their time in seventh gear and had to pedal steadily. They pedalled for 11 hours each day.

Another hazard was the ice-cracks, sometimes 8 cm wide, and often covered by snowdrifts.

“We felt so exposed out there” emphasizes Joanie. “There’s no protection. You wouldn’t want to get caught in a storm, there’s no place to put yourself.”

They both wore balaclavas, GoreTex hats with earflaps and pile lining, ski goggles to fit over glacier glasses, polypropylene underwear, fleece pants and top with a GoreTex outer shell, wool socks and cycling shoes.

“We were pretty comfortable,” Gary recalls. “The wind kicked up the second day and luckily it was behind us. It wouldn’t have been much fun to pedal into it.”

The couple spend two days and one night on the Ice Road and thanks to a CBC radio interview just before their departure, they had some unexpected visitors.

“There are no posted speed limits and I don’t think we were breaking any record anyway,” Joanie remembers. “So we were startled when an RCMP Twin Otter circled and landed right on the road.”

The police had heard the interview and just stopped by to see how they were. Later, a helicopter from a nearby drill-rig flew by to wish them well.

But for the McGuffins, the really special aspect of this first leg of their journey is the fact that only two years ago, they paddled over the same water they were now pedalling over.

This first leg had to be completed in early April. By June first the ferries at the MacKenzie and Peel Rivers are operational and the Dempster Highway is drying up. This is the cue for the McGuffins to start the next leg of their trip. In the meantime we’ll have to await the completion of this cycle traverse to learn what their next mode of self-propelled travel will be.

LOGISTICS: The Nuts and Bolts of Organizing a Long Distance Tour

by Gary and Joanie McGuffin

There are a number of special considerations that we have taken into account while planning the equipment and clothing for this 12,000 km cycling expedition from Tuktoyaktuk to L’Anse aux Meadows. The northerly route that we have chosen involves extended travel over rough bicycling terrain. The roads of northwestern Canada, being for the most part unpaved loose gravel, demand equipment durability first and foremost. Apart from this, one is limited to a certain amount of carrying capacity therefore light weight and compactness are also necessary considerations. However, we have maximised the use of space by using large volume panniers on both the front and rear racks, as well as a substantial handlebar bag for our photographic system.

Over the course of a five month journey that ranges in latitude from 70 degree North (‘Tuk’- on the Beaufort Sea) to 46 degree N (Ontario-Quebec border), the weather can vary tremendously. Not only will we have to deal with rainstorms, but in the final months of the journey we could face snowstorms. Each piece of clothing must be carefully chosen for its comfort, durability and function. Temperatures over the course of the expedition will range from a possible low of -35 degree Celsius at ‘Tuk’ to highs of 38 degree Celsius across inland Canada.

The clothing we have chosen to combat these conditions utilizes the layering system so a full foul weather system or a light nylon shell can be worn depending on conditions. One of the most important items of clothing are the cycling shorts. These are made from Lycra material with padded chamois crotch for comfort. Padded gloves, a rimmed hat and brightly coloured Vetta Corsair helmet are also important items.

They bicycles we have chosen for this trip are Norco-Nishiki Kodiak mountain bikes outfitted with dropped handlebars, high pressure on-off road balloon tires, and fenders. We have a full pannier system which helps to distribute the weight, and pannier covers for foul weather riding made from 6 oz. coated nylon.

Regular daily maintenance and cleaning of the bicycles’ working parts will ensure smooth operation and fewer breakdowns en route. We live by a rule that states, “If your bicycle is ‘talking’ to you, stop right away, be patient and cure its problem.” Bicycles are supposed to be smooth running machines. Clunks, scraping noises, etc. mean bad news. Some part is wearing where it shouldn’t be and if it isn’t fixed immediately it could spell trouble, even disaster! However, it takes great fortitude to live by this rule in wet and cold weather. Smooth riding with efficient gear changing while climbing in hilly terrain greatly reduces wear and tear on the chain, chainwheels, sprockets and derailleurs. Daily lubrication of the chain with a light oil such as WD-40 eliminates the problems that occur with heavier household oil, which attracts dirt and causes wear. All the moving parts of the front and rear derailleurs, brake pivot points and pedals need regular lubrication.

Whether it be an extended cycling journey, kayak excursion or backpacking trek, re-supplying ourselves with fresh batches of film, clothing to suit conditions, repair supplies and food could be difficult if it were not for the postal system and the RCMP detachments. Before setting off on this cycling expedition, we arranged to send our parcels containing film and maintenance supplies to RCMP detachments at regularly spaced intervals en route. Food is not a problem for the most part considering that towns are spaced within a two-to three-day’s ride. However, the postal system plays a major role in eliminating a considerable amount of excess baggage. Once we leave the western mountains, warm weather clothing will be sent through to a detachment in the Maritimes, for example. We also use the postal system to send home exposed film and daily log books on a regular basis.

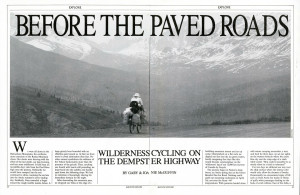

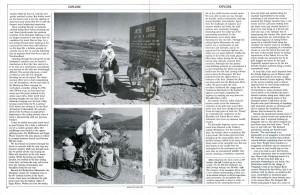

BEFORE THE PAVED ROADS WILDERNESS CYCLING ON THE DEMPSTER HIGHWAY

Wilderness Cycling On The Dempster Highway

By Joanie and Gary McGuffin

Article in Explore

We were all alone in the Richardson Mountains, the northern-most extension of the Rocky Mountain chain. Our chests were heaving with the effort of the last climb, our legs burning, and our seats saddlesore. It had been an incredible day’s ride from the Peel River high onto the plateau. Ordinarily we would have camped, but the sun continued to shine, warming the air late into the Arctic summer’s never-ending day. Suddenly, Gary extended a finger toward the rough tumble tundra below. A large grizzly bear bounded with an effortless gait toward us. At first we froze more in awed admiration than fear. No other animal symbolizes the wildness of the Yukon backcountry more than the presence of the grizzly. Then, catching our breath with hearts still pounding, we leapt back into the saddles and hastily sped down the following slope. We had no intention of knowingly sharing his immediate domain for the night. After descending the mountain pass, we dropped our bikes at the edge of a bubbling mountain stream and set up camp. Outstretched on a flat rock, we dipped our feet into the icy green waters, hardly imagining that days like this would become commonplace on the ‘wilderness’ leg of our 12,000 km traverse of Canada by bicycle.

We were all alone in the Richardson Mountains, the northern-most extension of the Rocky Mountain chain. Our chests were heaving with the effort of the last climb, our legs burning, and our seats saddlesore. It had been an incredible day’s ride from the Peel River high onto the plateau. Ordinarily we would have camped, but the sun continued to shine, warming the air late into the Arctic summer’s never-ending day. Suddenly, Gary extended a finger toward the rough tumble tundra below. A large grizzly bear bounded with an effortless gait toward us. At first we froze more in awed admiration than fear. No other animal symbolizes the wildness of the Yukon backcountry more than the presence of the grizzly. Then, catching our breath with hearts still pounding, we leapt back into the saddles and hastily sped down the following slope. We had no intention of knowingly sharing his immediate domain for the night. After descending the mountain pass, we dropped our bikes at the edge of a bubbling mountain stream and set up camp. Outstretched on a flat rock, we dipped our feet into the icy green waters, hardly imagining that days like this would become commonplace on the ‘wilderness’ leg of our 12,000 km traverse of Canada by bicycle.

The journey began in Nature’s deep-freeze, an Arctic spring day on the frozen Beaufort Sea Ice Road. Nothing could quell our mounting excitement on April 3rd, not even the -40 degree temperatures. With panniers loaded down with winter camping necessities, a tent, and food for three days, we set our sights on the western horizon where the azure blue sky met the crisp edge of a stark white world. “How could it possibly be so utterly silent in a land so immense?”

For two days we slithered our way over the slick surface where the intense cold would only allow the shortest of breaks. Occasionally, we encountered signs of life such as a fresh Arctic fox tracks or flocks of puffy white ptarmigan feeding on the buds of scrub willows. East of the delta, a reindeer lifted its head in curiosity and quietly watched us pass. But further north on the frozen road, it was the sighting of polar bear paw prints that left us with the deepest, most long lasting impression.

For two days we slithered our way over the slick surface where the intense cold would only allow the shortest of breaks. Occasionally, we encountered signs of life such as a fresh Arctic fox tracks or flocks of puffy white ptarmigan feeding on the buds of scrub willows. East of the delta, a reindeer lifted its head in curiosity and quietly watched us pass. But further north on the frozen road, it was the sighting of polar bear paw prints that left us with the deepest, most long lasting impression.

Upon reaching Inuvik, we patiently awaited spring thaw before resuming our trek. Since Inuvik marks the northern terminus of the Dempster highway, it was no longer necessary to rely upon firm ice conditions for travel. But on June 1st, a late spring blizzard came slashing at the coast and the rivers were still locked in ice. By June 8th, a definite promise of summer was in the air and the following day we departed from Inuvik en route to Newfoundland.

Grinding through the soft gravel on the Dempster’s northern end, we found it treacherous at first. Our tires swerved as if we were on a sand beach, and gaining any traction on the hills was frustratingly difficult. The second afternoon, a truck crowded us onto the soft shoulder throwing me out of control. The chain-reaction effect sent us both catapulting over the handlebars. On the east bank of the Mackenzie River crossing, we overlooked a familiar setting. In 1984, with 300 km to go, we had raced our canoe past this point onwards to the Arctic coast with a bitter north wind plowing straight into our faces, and whitecaps heaping over the bow. (After having canoed from the St. Lawrence Gulf, winter was closing in on our final destination Tuktoyaktuk. We actually deemed the Ice Road an appropriate beginning to the cycling journey since it made a physical link with our previous voyage.)

KAYAKING BAJA’S WILD COASTLINE

By Joanie and Gary McGuffin

Article in Explore, June/July 1996

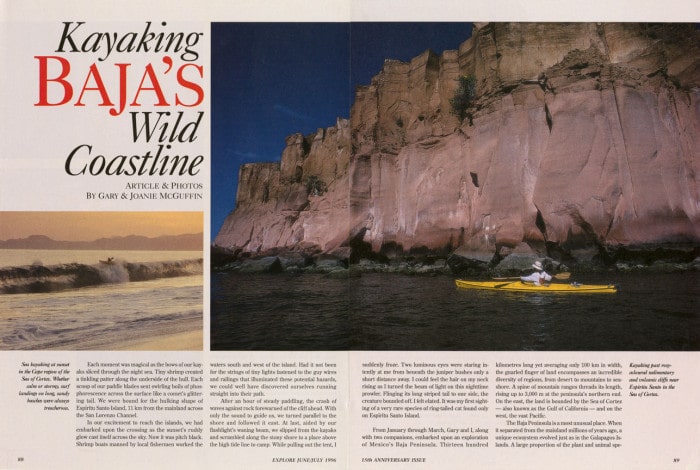

Each moment was magical as the bows of our kayaks sliced through the night sea. Tiny shrimp created a tinkling patter along the underside of the hull. Each scoop of our paddle blades sent swirling boils of phosphorescence across the surface like a comet’s glittering tail. We were bound for the hulking shape of Espiritu Santo Island, 11 km from the mainland across the San Lorenzo Channel.

Each moment was magical as the bows of our kayaks sliced through the night sea. Tiny shrimp created a tinkling patter along the underside of the hull. Each scoop of our paddle blades sent swirling boils of phosphorescence across the surface like a comet’s glittering tail. We were bound for the hulking shape of Espiritu Santo Island, 11 km from the mainland across the San Lorenzo Channel.

In our excitement to reach the islands, we had embarked upon the crossing as the sunset’s ruddy glow cast itself across the sky. Now it was pitch black. Shrimp boats manned by local fishermen worked the waters south and west of the island. Had it not been for the strings of tiny lights fastened to the guy wires and railings that illuminated these potential hazards, we could well have discovered ourselves running straight into their path.

After an hour of steady paddling, the crash of waves against rock forewarned of the cliff ahead. With only the sound to guide us, we turned parallel to the shore and followed it east. At last, aided by our flashlight’s waning beam, we slipped from the kayaks and scrambled along the stony shore to a place above the high tide line to camp. While pulling out the tent, I suddenly froze. Two luminous eyes were staring intently at me from beneath the juniper bushes only a short distance away. I could feel the hair on my neck rising as I turned the beam of light on this nighttime prowler. Flinging its long striped tail to one side, the creature bounded off. I felt elated. It was my first sighting of a very rare species of ring-tailed cat found only on Espiritu Santo Island.

From January through March, Gary and I, along with two companions, embarked upon an exploration of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula. Thirteen hundred kilometres long yet averaging only 100 km in width, the gnarled finger of land encompasses an incredible diversity of regions, from desert to mountains to seashore. A spine of mountain ranges threads its length, rising up to 3,000 m at the peninsula’s northern end. On the east, the land is bounded by the Sea of Cortez – also known as the Gulf of California – and on the west, the vast Pacific.

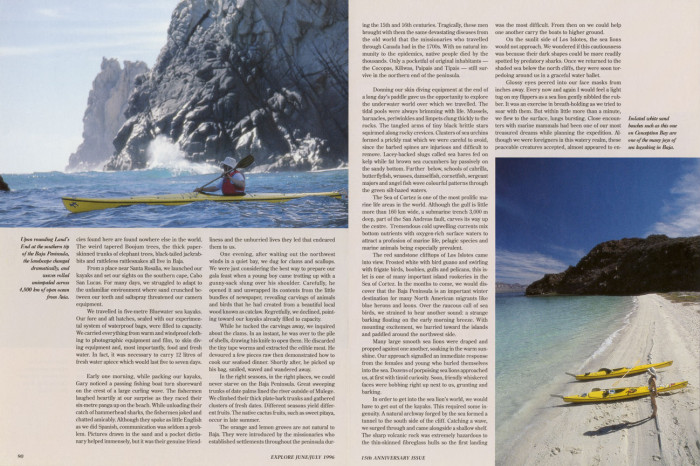

The Baja Peninsula is a most unusual place. When it separated from the mainland millions of years ago, a unique ecosystem evolved just as in the Galapagos Islands. A large proportion of the plant and animal species found here are found nowhere else in the world. The weird tapered Boojum trees, the thick paper-skinned trunks of elephant trees, black-tailed jackrabbits and rattleless rattlesnakes all live in Baja.

From a place near Santa Rosalia, we launched our kayaks and set our sights on the southern cape, Cabo San Lucas. For many days, we struggled to adapt to the unfamiliar environment where sand crunched between our teeth and salt spray threatened our camera equipment.

We travelled in five-metre Bluewater sea kayaks. Our fore and aft hatches, sealed with our experimental system of waterproof bags, were filled to capacity. We carried everything from warm and windproof clothing to photographic equipment and film, to skin diving equipment and, most importantly food and fresh water. In fact, it was necessary to carry 12 litres of fresh water apiece which would last five to seven days.

Early one morning, while packing our kayaks, Gary noticed a passing fishing boat turned shoreward on the crest of a large curling wave. The fishermen laughed heartily at our surprise as they raced their six-metre panga up on the beach. While unloading their catch of hammerhead sharks, the fishermen joked and chatted amicably. Although they spoke as little English as we did Spanish, communication was seldom a problem. Pictures drawn in the sand and a pocket dictionary helped immensely, but it was their genuine friendliness and the unhurried lives they led that endeared them to us.

One evening, after waiting out the northwest winds in a quiet bay, we dug for clams and scallops. We were just considering the best way to prepare our gala feast when a young boy came trotting up with a gunny-sack slung over his shoulder. Carefully, he opened it and unwrapped its contents from the little bundles of newspaper, revealing carvings of animals and birds that he had created from a beautiful local wood known as catclaw. Regretfully, we declined, pointing toward our kayaks already filled to capacity.

While he tucked the carvings away, we inquired about the clams. In an instant, he was over to the pile of shells, drawing his knife to open them. He discarded the tiny tape worms and extracted the edible meat. He devoured a few pieces raw then demonstrated how to cook our seafood dinner. Shortly after, he picked up his bag, smiled, waved and wandered away.

In the right seasons, in the right places, we could never starve on the Baja Peninsula. Great sweeping trunks of date palms lined the river outside of Mulege. We climbed their thick plate-bark trunks and gathered clusters of fresh dates. Different seasons yield different fruits. The native cactus fruits, such as sweet pitaya, occur in late summer.

The orange and lemon groves are not natural to Baja. They were introduced by the missionaries who established settlements throughout the peninsula during the 15th and 16th centuries. Tragically, these men brought with them the same devastating diseases from the old world that the missionaries who travelled through Canada had in the 1700s. With no natural immunity to the epidemics, native people died by the thousands. Only a pocketful or original inhabitants – the Cocopas, Killwas, Paipais and Tipais – still survive in the northern end of the peninsula.

Donning our skin diving equipment at the end of a long day’s paddle gave us the opportunity to explore the underwater world over which we travelled. The tidal pools were always brimming with life. Mussels, barnacles, periwinkles and limpets clung thickly to the rocks. The tangled arms of tiny black brittle stars squirmed along rocky crevices. Clusters of sea urchins formed a prickly mat which we were careful to avoid, since the barbed spines are injurious and difficult to remove. Lacey-backed slugs called sea hares fed on kelp while fat brown sea cucumbers lay passively on the sandy bottom. Further below, schools of cabrilla, butterflyfish, wrasses, damselfish, cornetfish, sergeant majors and angel fish wove colourful patterns through the green silt-hazed waters.

The Sea of Cortez is one of the most prolific marine life areas in the world. Although the gulf is little more than 160 km wide, a submarine trench 3,000 m deep, part of the San Andreas fault, carves its way up the centre. Tremendous cold upwelling currents mix bottom nutrients with oxygen-rich surface waters to attract a profusion of marine life, pelagic species and marine animals being especially prevalent.

The red sandstone clifftops of Los Islotes came into view. Frosted white with bird guano and swirling with frigate birds, boobies, gulls, and pelicans, this islet is one of many important island rookeries in the Sea of Cortez. In the months to come, we would discover that the Baja Peninsula is an important winter destination for many North American migrants like blue herons and loons. Over the raucous call of sea birds, we strained to hear another sound: a strange barking floating on the early morning breeze. With mounting excitement, we hurried toward the islands and paddled around the northwest side.

Many large smooth sea lions were draped and propped against one another, soaking in the warm sunshine. Our approach signalled an immediate response from the females and young who hurled themselves into the sea. Dozens of porpoising sea lions approached us, at first with timid curiosity. Soon, friendly whiskered faces were bobbing right up next to us, grunting and barking.

In order to get into the sea lion’s world, we would have to get out of the kayaks. This required some ingenuity. A natural archway forged by the sea formed a tunnel to the south side of the cliff. Catching a wave, we surged through and came alongside a shallow shelf. The sharp volcanic rock was extremely hazardous to the thin-skinned fibreglass hulls so the first landing was the most difficult. From then on we could help one another carry the boats to higher ground.

On the sunlit side of Los Islotes, the sea lions would not approach. We wondered if this cautiousness was because their dark shapes could be more readily spotted by predatory sharks. Once we returned to the shaded sea below the north cliffs, they were soon torpedoing around us in a graceful water ballet.

Glossy eyes peered into our face masks from inches away. Every now and again I would feel a light tug on my flippers as a sea lion gently nibbled the rubber. It was an exercise in breath-holding as we tried to soar with them. But within little more than a minute, we flew to the surface, lungs bursting. Close encounters with marine mammals had been one of our most treasured dreams while planning the expedition. Although we were foreigners in this watery realm, these peaceable creatures accepted, almost appeared to enjoy, our presence. We played with them until the cold finally won, forcing us back to the land.

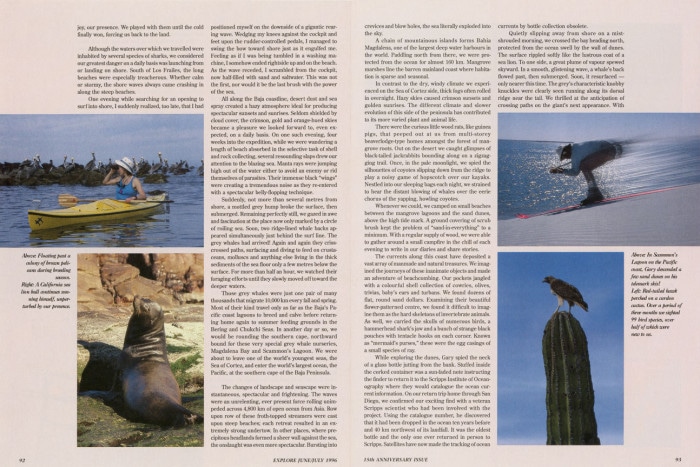

Although the waters over which we travelled were inhabited by several species of sharks, we considered our greatest danger on a daily basis was launching from or landing on shore. South of Los Frailes, the long beaches were especially treacherous. Whether calm or stormy, the shore waves always came crashing in along the steep beaches.

One evening while searching for an opening to surf into shore, I suddenly realized, too late, that I had positioned myself on the downside of a gigantic rearing wave. Wedging my knees against the cockpit and feet upon the rudder-controlled pedals, I managed to swing the bow toward shore just as it engulfed me. Feeling as if I was being tumbled in a washing machine, I somehow ended rightside up and on the beach. As the wave receded, I scrambled from the cockpit, now half-filled with sand and saltwater. This was not the first, nor would it be the last brush with the power of the sea.

All along the Baja coastline, desert dust and sea spray created a hazy atmosphere ideal for producing spectacular sunsets and sunrises. Seldom shielded by cloud cover, the crimson, gold and orange-hued skies became a pleasure we looked forward to, even expected, on a daily basis. On one such evening, four weeks into the expedition, while we were wandering a length of beach absorbed in the selective task of shell and rock collecting, several resounding slaps drew our attention to the blazing sea. Manta rays were jumping high out of the water either to avoid an enemy or rid themselves of parasites. Their immense black “wings” were creating a tremendous noise as they re-entered with a spectacular belly-flopping technique.

Suddenly, not more than several metres from shore, a mottled grey hump broke the surface, then submerged. Remaining perfectly still, we gazed in awe and fascination at the place now only marked by a circle of roiling sea. Soon, two ridge-lined whale backs appeared simultaneously just behind the surf line. The grey whales had arrived! Again and again they crisscrossed paths, surfacing and diving to feed on crustaceans, molluscs and anything else living in the thick sediments of the sea floor only a few metres below the surface. For more than half an hour, we watched their foraging efforts until they slowly moved off toward the deeper waters.

Those grey whales were just one pair of many thousands that migrate 10,000 km every fall and spring. Most of their kind travel only as far as the Baja’s Pacific coast lagoons to breed and calve before returning home again to summer feeding grounds in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. In another day or so, we would be rounding the southern cape, northward bound for these very special grey whale nurseries, Magdalena Bay and Scammon’s Lagoon. We were about to leave one of the world’s youngest seas, the Sea of Cortez, and enter the world’s largest ocean, the Pacific, at the southern cape of the Baja Peninsula.

Those grey whales were just one pair of many thousands that migrate 10,000 km every fall and spring. Most of their kind travel only as far as the Baja’s Pacific coast lagoons to breed and calve before returning home again to summer feeding grounds in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. In another day or so, we would be rounding the southern cape, northward bound for these very special grey whale nurseries, Magdalena Bay and Scammon’s Lagoon. We were about to leave one of the world’s youngest seas, the Sea of Cortez, and enter the world’s largest ocean, the Pacific, at the southern cape of the Baja Peninsula.

The changes of landscape and seascape were instantaneous, spectacular and frightening. The waves were an unrelenting, ever present force rolling unimpeded across 4,800 km of open ocean from Asia. Row upon row of these froth-topped streamers were cast upon steep beaches; each retreat resulted in an extremely strong undertow. In other places, where precipitous headlands formed a sheer wall against the sea, the onslaught was even more spectacular. Bursting into crevices and blow holes, the sea literally exploded into the sky.

A chain of mountainous islands forms Bahia Magdalena, one of the largest deep water harbours in the world. Paddling north from there, we were protected from the ocean for almost 160 km. Mangrove marshes line the barren mainland coast where habitation is sparse and seasonal.

In contrast to the dry, windy climate we experienced on the Sea of Cortez side, thick fogs often rolled in overnight. Hazy skies caused crimson sunsets and golden sunrises. The different climate and slower evolution of this side of the peninsula has contributed to its more varied plant and animal life.

There were the curious little wood rats, like guinea pigs, that peeped out at us from multi-storey beaverlodge-type homes amongst the forest of mangrove roots. Out on the desert we caught glimpses of black-tailed jackrabbits bounding along a zigzagging trail. Once, in the pale moonlight, we spied the silhouettes of coyotes slipping down from the ridge to play a noisy game of hopscotch over our kayaks. Nestled into our sleeping bags each night, we strained to hear the distant blowing of whales over the eerie chorus of the yapping, howling coyotes.

Whenever we could, we camped on small beaches between the mangrove lagoons and the sand dunes, above the high tide mark. A ground covering of scrub brush kept the problem of “sand-in-everything” to a minimum. With a regular supply of wood, we were able to gather around a small campfire in the chill of each evening to write in our diaries and share stories.

The currents along this coast have deposited a vast array of manmade and natural treasures. We imagined the journeys of these inanimate objects and made an adventure of beachcombing. Our pockets jangled with a colourful shell collection of cowries, olives, trivias, baby’s ears and turbans. We found dozens of flat, round sand dollars. Examining their beautiful flower-patterned centre, we found it difficult to imagine them as the hard skeletons of invertebrate animals. As well, we carried the skulls of numerous birds, a hammerhead shark’s jaw and a bunch of strange black pouches with tentacle hooks on each corner. Known as “mermaid’s purses,” these were the egg casings of a small species of ray.

While exploring the dunes, Gary spied the neck of a glass bottle jutting from the bank. Stuffed inside the corked container was a sun-faded note instructing the finder to return it to the Scripps Institute of Oceanography where they would catalogue the ocean current information. On our return trip home through San Diego, we confirmed our exciting find with a veteran Scripps scientist who had been involved with the project. Using the catalogue number, he discovered that it had been dropped in the ocean ten years before and 40 km northwest of its landfall. It was the oldest bottle and the only one ever returned in person to Scripps. Satellites have now made the tracking of ocean currents by bottle collection obsolete.

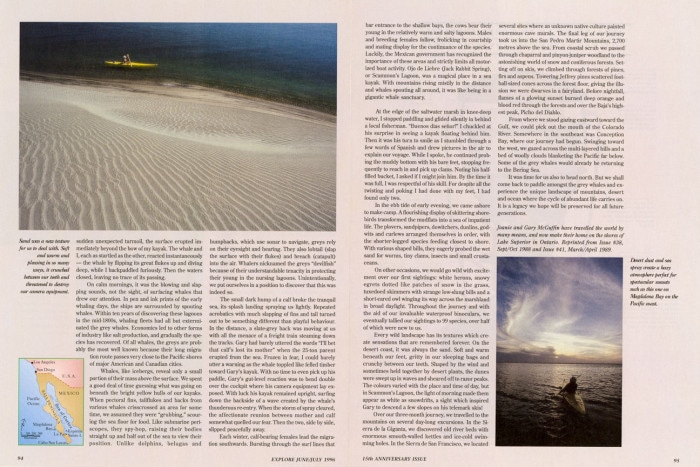

Quietly slipping away from shore on a mist-shrouded morning, we crossed the bay heading north, protected from the ocean swell by the wall of dunes. The surface rippled softly like the lustrous coat of a sea lion. To one side, a great plume of vapour spewed skyward. In a smooth, glistening wave, a whale’s back flowed past, then submerged. Soon, it resurfaced – only nearer this time. The grey’s characteristic knobby knuckles were clearly seen running along its dorsal ridge near the tail. We thrilled at the anticipation of crossing paths on the giant’s next appearance. With sudden unexpected turmoil, the surface erupted immediately beyond the bow of my kayak. The whale and I, each as startled as the other, reacted instantaneously – the whale by flipping its great flukes up and diving deep, while I back paddled furiously. Then the waters closed, leaving no trace of its passing.

On calm mornings, it was the blowing and slapping sounds, not the sight, of surfacing whales that drew our attention. In pen and ink prints of the early whaling days, the ships are surrounded by spouting whales. Within ten years of discovering these lagoons in the mid-1800s, whaling fleets had all but exterminated the grey whales. Economics let to other forms of industry like salt production, and gradually the species has recovered. Of all whales, the greys are probably the most well known because their long migration route passes very close to the Pacific shores of major American and Canadian cities.

Whales, like icebergs, reveal only a small portion of their mass above the surface. We spent a good deal of time guessing what was going on beneath the bright yellow hulls of our kayaks. When pectoral fins, tail flukes and backs from various whales crisscrossed an area for sometime, we assumed they were “grubbing,” scouring the sea floor for food. Like submarine periscopes, they spy-hop, raising their bodies straight up and half out of the sea to view their position. Unlike dolphins, belugas and humpbacks, which use sonar to navigate, greys rely on their eyesight and hearing. They also lobtail (slap the surface with their flukes) and breach (catapult) into the air. Whalers nicknamed the greys “devilfish” because of their understandable tenacity in protecting their young in the nursing lagoons. Unintentionally, we put ourselves in position to discover that this was indeed so.

The small dark hump of a calf broke the tranquil sea, its splash landing spraying us lightly. Repeated acrobatics with much slapping of fins and tail turned out to be something different than playful behaviour. In the distance, a slate-grey back was moving at us with all the menace of a freight train steaming down the tracks. Gary had barely uttered the words “I’ll bet that calf’s lost its mother” when the 25-ton parent erupted from the sea. Frozen in fear, I could barely utter a warning as the whale toppled like felled timber toward Gary’s kayak. With no time to even pick up his paddle, Gary’s gut-level reaction was to bend double over the cockpit where his camera equipment lay exposed. With luck his kayak remained upright, surfing down the backside of a wave created by the whale’s thunderous re-entry. When the storm of spray cleared, the affectionate reunion between mother and calf somewhat quelled our fear. Then the two, side by side slipped peacefully away.

Each winter, calf-bearing females lead the migration southwards. Bursting through the surf lines that bar entrance to the shallow bays, the cows bear their young in the relatively warm and salty lagoons. Males and breeding females follow, frolicking in courtship and mating display for the continuance of the species. Luckily, the Mexican government has recognized the importance of these areas and strictly limits all motorized boat activity. Ojo de Liebre (Jack Rabbit Spring), or Scammon’s Lagoon, was a magical place in a sea kayak. With mountains rising mistily in the distance and whales spouting all around, it was like being in a gigantic whale sanctuary.

At the edge of the saltwater marsh in knee-deep water, I stopped paddling and glided silently in behind a local fisherman. “Buenos dias senor!” I chuckled at his surprise in seeing a kayak floating behind him. Then it was his turn to smile as I stumbled through a few words of Spanish and drew pictures in the air to explain our voyage. While I spoke, he continued probing the muddy bottom with his bare feet, stopping frequently to reach in and pick up clams. Noting his half-filled bucket, I asked if I might join him. By the time it was full, I was respectful of his skill. For despite all the twisting and poking I had done with my feet, I had found only two.

In the ebb tide of early evening, we came ashore to make camp. A flourishing display of skittering shore-birds transformed the mudflats into a sea of impatient life. The plovers, sandpipers, dowitchers, dunlins, godwits and curlews arranged themselves in order, with the shorter-legged species feeding closest to shore. With various shaped bills, they eagerly probed the wet sand for worms, tiny clams, insects and small crustaceans.

On other occasions, we would go wild with excitement over our first sightings: white herons, snowy egrets dotted like patches of snow in the grass, tuxedoed skimmers with strange low-slung bills and a short-eared owl winging its way across the marshland in broad daylight. Throughout the journey and with the aid of our invaluable waterproof binoculars, we eventually tallied our sightings to 99 species, over half of which were new to us.

Every wild landscape has its textures which create sensations that are remembered forever. On the desert coast, it was always the sand. Soft and warm beneath our feet, gritty in our sleeping bags and crunchy between our teeth. Shaped by the wind and sometimes held together by desert plants, the dunes were swept up in waves and sheared off to razor peaks. The colours varied with the place and time of day, but in Scammon’s Lagoon, the light of morning made them appear as white as snowdrifts, a sight which inspired Gary to descend a few slopes on his telemark skis!

Over our three-month journey, we travelled to the mountains on several day-long excursions. In the Sierra de la Giganta, we discovered old river beds with enormous smooth-walled kettles and ice-cold swimming holes. In the Sierra de San Francisco, we located several sites where an unknown native culture painted enormous cave murals. The final leg of our journey took us into the San Pedro Martir Mountains, 2,700 metres above the sea. From coastal scrub we passed through chaparral and pinyon-juniper woodland to the astonishing world of snow and coniferous forests. Setting off on skis, we climbed through forests of pines, firs and aspens. Towering Jeffrey pines scattered football-sized cones across the forest floor, giving the illusion we were dwarves in a fairyland. Before nightfall, flames of a glowing sunset burned deep orange and blood red through the forests and over the Baja’s highest peak, Picho del Diablo.

From where we stood gazing eastward toward the Gulf, we could pick out the mouth of the Colorado River. Somewhere in the southeast was Conception Bay, where our journey had begun. Swinging toward the west, we gazed across the multi-layered hills and a bed of woolly clouds blanketing the Pacific far below. Some of the grey whales would already be returning to the Bering Sea.

It was time for us also to head north. But we shall come back to paddle amongst the grey whales and experience the unique landscape of mountains, desert and ocean where the cycle of abundant life carries on. It is a legacy we hope will be preserved for all future generations.