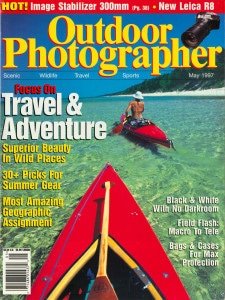

Superior Adventure

Truly wild country can be found in places other than the West

By James Lawrence

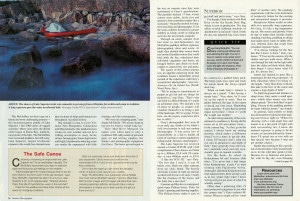

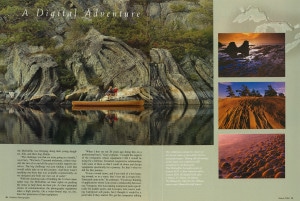

Photography by Joanie and Gary McGuffin

Article in Outdoor Photographer, May 1997

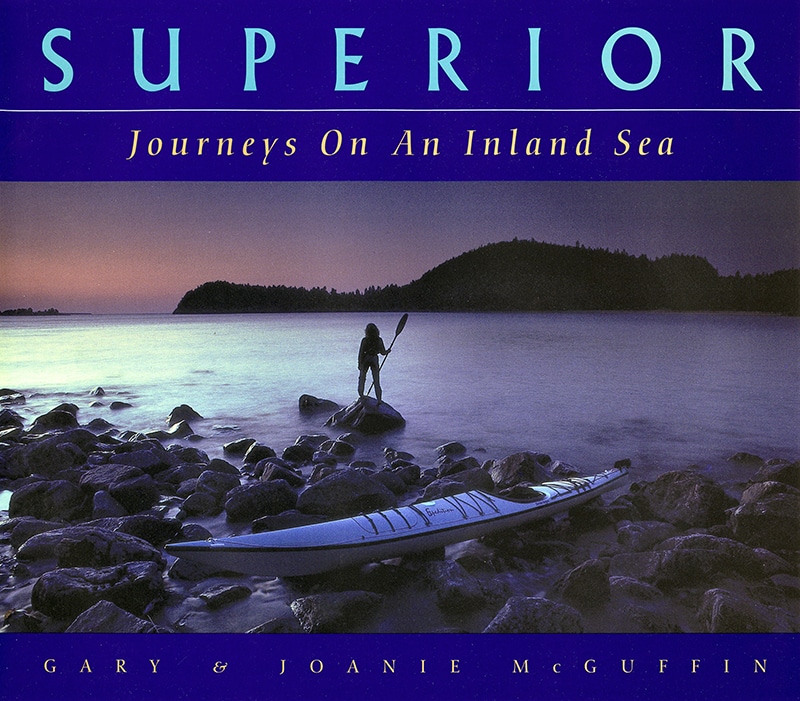

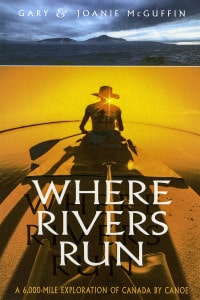

Joanie and Gary McGuffin like going in circles. Canadian born and bred, Great Lakes nature babies, these hardy adventurers spend more time outdoors in a year than most of us in a lifetime, roving the loop of seasons, light and time in the vastness of nature. Back in the ‘80s, barely underway on an ambitious honeymoon canoe odyssey across Canada, they had to make a 500-mile north coast traverse of vast Lake Superior. Superior revealed a most beguiling and spiritually uplifting facet of its complex persona – almost two weeks of balmy weather and smooth passage. Right there the seed was planted.

The McGuffins set their caps on a future and most challenging journey – the circumnavigatory paddle of Lake Superior’s full 2000 miles of rugged coastline. Many years later, the dream circle began at Kama Bay, northern-most point of the lake. The McGuffins were seasoned paddlers, but still wary: Lake Superior, largest freshwater expanse in the world, has claimed more than its share of ships and human lives throughout recorded history.

Big enough in area to cover Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut and Massachusetts, this landlocked sea creates its own weather and can be a willing accomplice to nasty Arctic storms. Savage gales, house-high waves, and frigid, hypothermia-inducing water can sunder the unprepared with little warning and dire consequence.

“We were on a sleeping giant,” says Joanie McGuffin. “We always kept an eye out for when it would wake up.”

Their Mad River Monarch sea canoes were called upon to carry a combined 200-odd pounds of personal gear, art and writing supplies (for Joanie) and photographic equipment (for Gary). The boats proved equal to the test, no surprise since they were customized to Gary’s specifications. The partially decked, 17-foot, 4-inch canoes were stable, fairly fast and sported a foot-controlled rudder like a sea kayak – the perfect hybrid for long-term traveling and photography. Even the seats could be lowered for greater stability in windy swells or riding the surf into the next beach campsite.

Through an entire summer from late June to mid-September, the McGuffins paddled, drifted, explored, photographed, drew and wrote. At night, they pitched their roomy dome tent on the friendliest shore they could find, built the fire, rehydrated their self-dried vegetables and fruits, ate foraged berries and dined on fresh-caught or canned fish, rice and pasta.

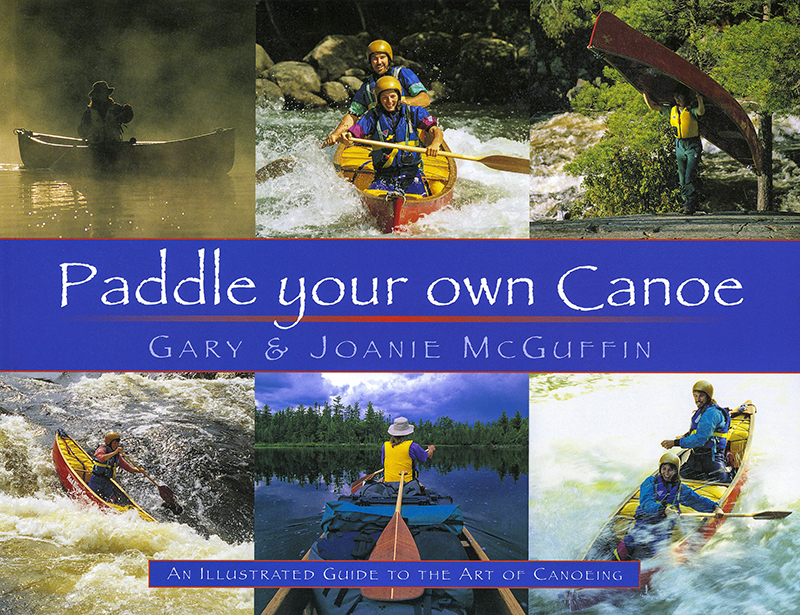

The spawn of this robust journey was an appetite-satisfying book that combines Joanie’s beautifully lyrical journal of experience with Gary’s exceptional photography: Superior: Journeys On An Inland Sea (NorthWord Press, Inc.).

“We’re trying to communicate to people to get out and see things for themselves,” Says Gary. “That’s why our book is a little different. It’s really an adventure story. We include a lot of shots of people, so readers will visualize themselves as being a part of the landscape. We’re saying, ‘Come here, see the region, experience all it has to offer.’”

Gary’s photographic fires were lit at an early age, thanks to his father’s avid involvement in still and motion photography. “I was given lots of responsibility as a kid to handle all kinds of expensive camera equipment, fishing tackle, firearms, small engines.”

His Lake Superior kit revolved around a Contax RTS III with a full complement of Zeiss lenses: an 18mm up to a 300mm f/2.8 with 2X extender – a nice 600mm reach at f/5.6.

“I like the RTS III,” says Gary. “The first time I used it, it was 45 below zero. Both my older cameras froze up: click, thunk. The heavily electronic Contax lit right up and has worked well for me ever since. I really like the crispness of the lenses, and the body has a nice feel.”

Cameras and film live in waterproof, quick-open Pelican boxes. Ditto for Joanie’s painting and drawing supplies. “The Pelican boxes make it easy to get stuff and put it away,” says Gary.

For kayaks, Gary worked with Mad River on the Sea Kayak Deck Bag, which is now in production. The bag offers several different methods of attachments to a sea kayak’s deck. Inside the dry-suit zippered bag, Gary keeps his cameras in a padded fanny pack. The fanny pack stays open and ready for action inside the always-zipped deck bag.

When on land. Gary’s camera is always on a tripod. “I like having a steady base.” Near shore, he’ll even set up the tripod in water. Then he glides between the legs in his canoe or kayak and fires away. Shutterbug meets waterbug. “ I carry that six-pound tripod everywhere. I think it’s worth the weight and trouble.”

An interesting mainstay of his commitment to readiness is having all the lenses set at f/8 and infinity focus – in the camera bag. “As they go on the camera, I always know my starting position, which makes a difference when I’m in a hurry to get the shot. I chose f/8 because that’s what my eye sees in perspective and depth of field.” Gary generally trusts the Contax’s automatic meter and only occasionally goes to manual override.

For the book, he relied on Kodachrome 64 and Lumiere slide films. “I’ve never had a bad image from Kodachrome. Lately, I’ve been working with Fujichrome Velvia. Although I still think Kodachrome has truer natural colors, there are days such as in low winter light when I know Velvia will give me more of what I’m actually seeing.”

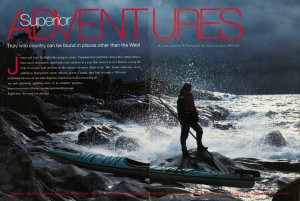

Other than a polarizing filter (“I wear polarized sunglasses to see what the camera sees”), Gary eschews filtration. What you might call his “mind filter” is another story. He regularly experiments with the color distortions of reciprocity failure for the exciting and unexpected images it provides.

Reciprocity failure results in color shift over unusually long exposures. For Gary, it’s like a big fingerpainting set. His serene and ghostly vistas by day or night often include Joanie standing, kneeling, paddling or skiing near made-misty water or subtly effusive, ethereal skies that result from extended exposure times.

“I’m always looking for the hidden that I know is there,” Gary continues. “I’ll set up the camera, trip the shutter and just walk away. When I sort through the take on the light table later, the slides are black, black, black, then bingo! I never know what I’ll get. It’s always fun.”

Joanie has learned to pose like a mannequin for the long exposures. “It feels ridiculous when I’m doing it,” she laughs. “Gary likes those verticals that take in the bow of the canoe and require a long depth of field.”

To hold foreground and distance in sharp focus, Gary needs a small aperture – which often means very slow shutter speeds. “So to look like I’m paddling, I freeze in the paddling position he wants while he shoots,” says Joanie.

In general, Gary prefers to think less about perfect exposures than making sure focus is right on. “When I’m shooting with a wide-angle lens and Joanie is in a pin prick of light with dark surrounding her, I know the metered exposure is going to be hit or miss, so I just bracket heavily. Sometimes Ill spend one or two rolls on that special shot because I may not get another chance.”

Rather than looking to fill a specific list of desired shots, Gary learned early on to let the wild lake speak to him. Because it’s so immense and powerful, with its big sky, ever-changing weather and hardy landscape, he always found something different “and even more interesting” than what he had first thought to get.

“I’ve spent lot of time in the Canadian Arctic and Greenland. There are certain places there where you have this feeling that the land knows you’re there, as if everything you do is accounted for by everything else around you. Lake Superior was that kind of place for us. It was a great place to do good things.”

Sometimes the McGuffins’ experiences were downright mystical. Once they paused when a bright point of light caught their eye. They looked up to see a peregrine falcon sitting atop a 150-foot-high bluff directly above them. As if on cue, the bird of prey took wing, flew over their heads, then swung in dramatically toward the cliff face and disappeared.

“We paddled on until we reached that point,” Gary continues. “When we looked up to the spot where the falcon had seemed to disappear into the rock, we saw a small opening. We climbed up and realized it was a cave. Nearby we found pictographs painted with red ochre left by the Anishnabe. Pictographs usually tell stories of their lives or predictions of how their lives will play out.”

“So much of it hasn’t changed,” Joanie reflects on the region. “The land itself was laid bare by the ice age. Different time frames happen for you on Superior. It can’t feel much different now than 10,000 years ago or a billion years ago. We tend to live so much in the immediate that it can tend to separate us from everything around us.”

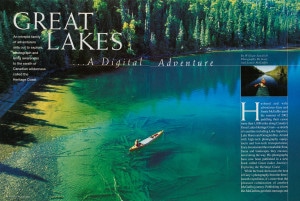

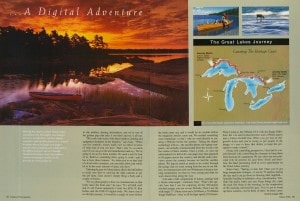

GREAT LAKES A DIGITAL ADVENTURE

An intrepid family of adventurers sets out to explore, photograph and bring awareness to the swath of Canadian wilderness called the Heritage Coast

By William Sawalich

Photography By Gary and Joanie McGuffin

Article in Outdoor Photographer, March 2004

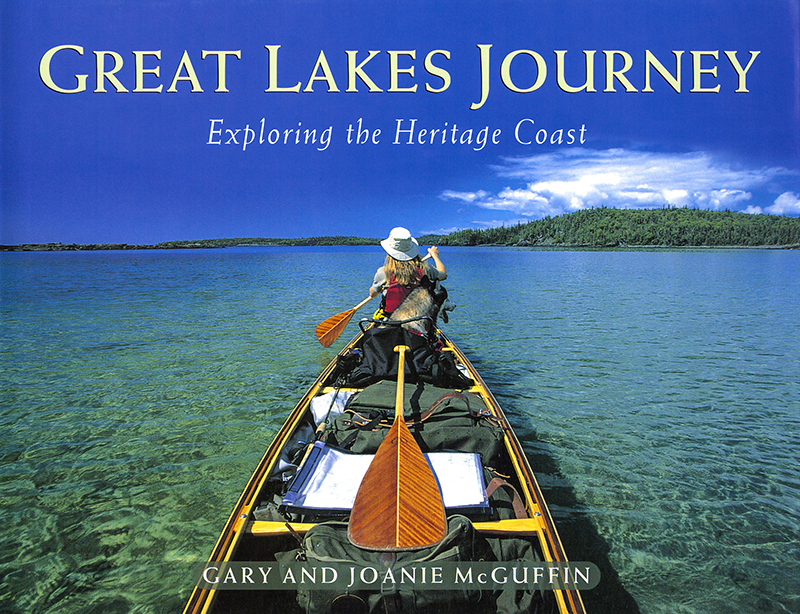

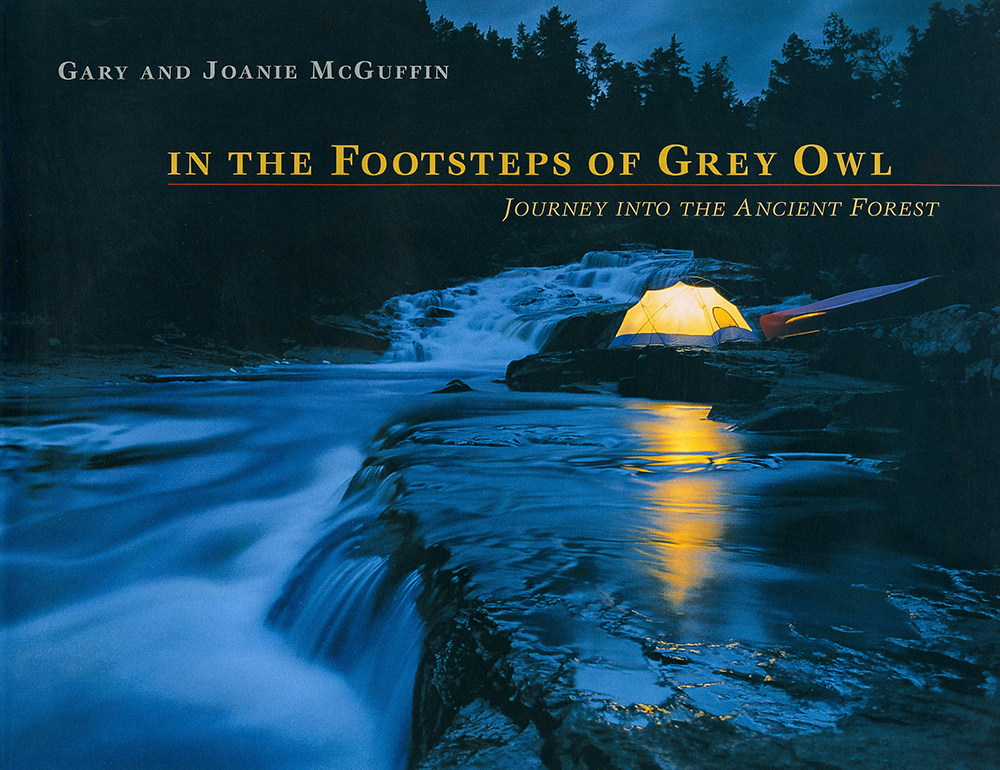

Husband and wife adventurers Gary and Joanie McGuffin spent the summer of 2002 paddling their canoe more than 1,800 miles along Canada’s Great Lakes Heritage Coast – a stretch of coastline including Lake Superior, Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. Armed with high-tech photography equipment and low-tech transportation, Gary documented the remarkable flora, fauna and landscapes they encountered along the way. His photographs have now been published in a new book called Great Lakes Journey: Exploring the Heritage Coast.

Husband and wife adventurers Gary and Joanie McGuffin spent the summer of 2002 paddling their canoe more than 1,800 miles along Canada’s Great Lakes Heritage Coast – a stretch of coastline including Lake Superior, Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. Armed with high-tech photography equipment and low-tech transportation, Gary documented the remarkable flora, fauna and landscapes they encountered along the way. His photographs have now been published in a new book called Great Lakes Journey: Exploring the Heritage Coast.

While the book showcases the best of Gary’s photography from the three-month expedition, it’s more than the pleasant culmination of another McGuffin journey. Publishing is how the McGuffins get their message out to the masses – a message of concern for the natural world.

“We’re asked to host television programs, radio, you name it,” says Gary from their home on the North Shore of Lake Superior. “But books are what we like to do best because they’re very personal. They’re based on wilderness expeditions, and wilderness expedition is a very personal, long-term lifetime commitment.”

That lifelong commitment to the outdoors began when they were very young. Their parents were explorers who instilled in them a reverence for the wilderness. Now, Gary and Joanie work together to explore and protect the Canadian wilderness. They’ve even made it a way of life.

“Though the Lands for Life process,” Gary explains, “the government of Ontario adopted the single largest initiative by any province in Canada to protect wild lands in the history of this nation. Three hundred seventy-eight new parks and protected areas were created as a result of this process, so it was a great win.”

At the start of the initiative, Gary and Joanie told a friend that if it were to pass, they’d paddle its length in order to help raise awareness of the region. “We were the folks who knew what was on the landscape because we have traveled it most of our lives,” says Gary. “So we were able to supply them with the on-ground data. That’s why the photography played a huge role.”

GETTING UNDER WAY

As anyone who sets off on a summer-long paddling journey can attest, there are a number of challenges in organizing such an expedition, not the least of which for the McGuffins was bringing along their young daughter, Sila, and their dog, Kalija.

As anyone who sets off on a summer-long paddling journey can attest, there are a number of challenges in organizing such an expedition, not the least of which for the McGuffins was bringing along their young daughter, Sila, and their dog, Kalija.

“The challenge was that we were going as a family,” says Gary. “We had a 75-pound malamute, a three-year-old, the two of us and all the gear to totally support ourselves. The big challenge was just finding a craft that would safely take us on this journey. And there wasn’t anything out there that was available commercially, so we designed and built our own out of cedar.”

With the daunting task of building the 21-foot canoe under way, the McGuffins set their sights on packing the items to help them do their job. As their principal means of communication, the photography equipment takes a high priority. On a water-bound trip, so, too, does the protection of that equipment.

“When I first set out 20 years ago doing this on a professional basis,” Gary explains, “I sought the support of the companies whose equipment I felt I would be using for a lifetime. I fostered cooperative relationships with some of them so that I could sit down and design equipment specifically for a journey. So, that’s what we did for this journey.

“It was a wood canoe, and I was tired of a box banging around, so in a sense, that’s how the Lowepro Dry-Zone pack came to be,” he continues. “I’m always thinking of applications where I can create a relationship between, say Voyageur, who was making waterproof packs specifically for paddle sports, and Lowepro, who wasn’t making waterproof soft packs, but I thought it would be a good idea if they started. We get the companies talking to one another, sharing information, and we’re sort of the guinea pigs that take it out there and try it all out.

“We work with some of the finest outdoor clothing and equipment designers in the business,” says Gary. “When you live outdoors, money really isn’t an object in terms of what kind of tent you have. That’s why it’s so much nicer if you can go to the tent manufacturer and say, ‘We’re going to be out for three months. We need a tent for four of us. Build us something that’s going to work – and it has to have these features.’ So, when you’re on that kind of a level with a company, you can really tailor your whole kit to fit the exact amount of space you have.”

Tailoring the gear to fit the journey allows the McGuffins to make sure they’re carrying the right cameras to get the job done. Gary doesn’t simply bring a body and a couple of lenses.

“For us, photography is how we communicate, so that really takes the front seat,” he says. “It’s all SLR stuff and it’s all Canon equipment. I took two EOS-1V film bodies and the EOS-1D digital body. We knew that if we did this journey, it would be a couple of years before the book came out, and it would be six months before the magazine articles came out. We needed something more immediate, so that’s why we went directly to creating a Website before the journey. Taking the digital technology with us – the satellite phone, the laptop computer – we actually communicated from the woods over the course of three months. Once a week, we sent out information for a full-color, one-page story that appeared in 58 papers across the country, and did the radio interviews across the country because we had the satellite phone. We kept in touch as much as we could, through the energy that we were storing from the sun in our battery, to communicate with our Webmaster to keep a running commentary on what we were seeing and what we were discovering along the way.

“For us, photography is how we communicate, so that really takes the front seat,” he says. “It’s all SLR stuff and it’s all Canon equipment. I took two EOS-1V film bodies and the EOS-1D digital body. We knew that if we did this journey, it would be a couple of years before the book came out, and it would be six months before the magazine articles came out. We needed something more immediate, so that’s why we went directly to creating a Website before the journey. Taking the digital technology with us – the satellite phone, the laptop computer – we actually communicated from the woods over the course of three months. Once a week, we sent out information for a full-color, one-page story that appeared in 58 papers across the country, and did the radio interviews across the country because we had the satellite phone. We kept in touch as much as we could, through the energy that we were storing from the sun in our battery, to communicate with our Webmaster to keep a running commentary on what we were seeing and what we were discovering along the way.

“I do take a full complement of lenses, starting with a 14mm wide-angle,” continues Gary. “That’s the specific lens that I use for capturing all the 360-degree stitched images you see on our Website. Then I use the wide-angle 17-35mm zoom and a 28-80mm, a 70-200mm Image Stabilizer – they’re all the high-speed f/2.8 lenses.

Then I jump to the 300mm f/2.8 with the Image Stabilizer, the 1.4x and 2x teleconverters and a 100mm macro and a 24mm tilt-shift lens. When you get into an old-growth forest and you’re trying to put people in the image, it’s nice to have that ability to keep the perspective under control.”

Along with controlling perspective, Gary had to concern himself with controlling perspective, Gary had to concern himself with controlling the elements to keep them from harming his equipment. He says there are two principal evils he protects hi gear from: shock and moisture, the latter presenting itself at every opportunity on the Great Lakes journey.

Notes Gary, “Spring, or into fall, when you’ve got huge temperature changes – it can be 75 degrees during the day and it can go down to freezing after nightfall – humidity buildup is definitely a key consideration. Ventilate the packs when you can. Keep things dry, open the pack first thing in the morning, let the temperature of the morning surround the gear. You’ve got to warm up those cameras, not let them sit there. In many cases, you learn the hard way.”

And, in the course of protecting his gear from winding up on the bottom of Lake Superior, Gary doesn’t simply lock away all his gear until he reaches camp. Part of the success of his photography is in the spontaneity of his approach. That means having the camera available at any moment.

“It’s adventure photography,” he explains. “You’ve only got a few seconds. You’re out there paddling, you see the way the light is changing. There’s the shot. You’ve got to scramble out and have the pack on your back, tripod ready, run to that spot, set up….”

ADVENTURE PHOTOGRAPHY

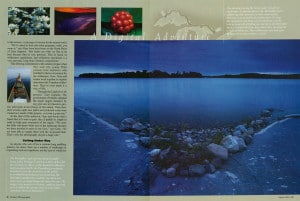

Some images in the book hold special meaning for the McGuffins, but don’t ask them to pick a favorite. Instead, they prefer the memories of the journey associated with certain shots.

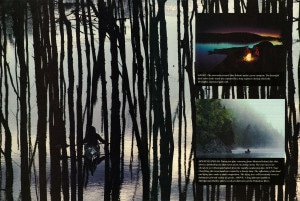

“We were there for three days in a huge wind,” Gary describes of an image of a flying kite in the book. “The seas were massive, the waves were 10 or 15 feet high, and you can see that big breaking wave on the way in to where Joanie is flying Sila’s kite. I’m standing in waist-deep water and the wave has just come past me. Imogene Bay is an old logging camp, and at one time, there was a community of 400 people that lived there. Now it’s totally reverted to wilderness. So, I look at that image and it brings back what a great three days it was running up and down that beach – just being there for three days without another soul around.”

Other photographs offer the opportunity to recall profound personal moments they experienced during the expedition.

“That’s on top of a place called the Sleeping Giant,” Gary remarks of another dramatic photograph in the book. “That’s just over 800 feet in height. What’s really neat about this place is the tops of the glaciers were about this high. The first people who came to this area exploring along the bottoms of those glaciers were walking along the tops of these cliffs. So, to stand there and imagine looking down and watching for woolly mammoths doing their seasonal migration, and then coming across spear points that are literally eight inches long and four inches in height and perfectly tooled – it’s amazing stuff to come across.

“That’s on top of a place called the Sleeping Giant,” Gary remarks of another dramatic photograph in the book. “That’s just over 800 feet in height. What’s really neat about this place is the tops of the glaciers were about this high. The first people who came to this area exploring along the bottoms of those glaciers were walking along the tops of these cliffs. So, to stand there and imagine looking down and watching for woolly mammoths doing their seasonal migration, and then coming across spear points that are literally eight inches long and four inches in height and perfectly tooled – it’s amazing stuff to come across.

“You’re standing there looking out with an entirely different perspective on what youre doing, compared to somebody standing there 10,000 years ago whose mission was to fee his family and his tribespeople. You feel so connected when you’ve been traveling by a traditional method – whether it’s walking or snowshoeing or canoeing or kayaking. You have more of an affinity with the person who left that spear point behind.

“I just don’t get compelled to pick the camera up and try to shoot something,” Gary says. “I’m much more interested in experience. When you’re on a journey, it’s a spiritual, emotional, physical, mental challenge. You’re so connected with everything. That’s what our photography represents. The camera came out; it went away when we finished the journey.

“That’s what adventure photography is to me as compared to maybe landscape photography, where someone decides they want to put a book together on a subject and they go back to it year after year, season after season, waiting for lengths of time for the light to be right. With this book, that’s what we saw when we were there. We’re taking you there to the best of our ability through these images.

“The journey is the experience,” Gary adds. “The book and the images are just a total celebration of that journey.”

The McGuffins hope that readers will not only fin the images beautiful and compelling, but inspiring as well. They hope to create appreciation for the environment and to help motivate positive changes in the natural world.

“In order to get people to defend a place, they have to come to love it,” says Gary. “I hope that even if people can’t come to the Great Lakes Heritage Coast, if they can’t get to these places, hopefully weve brought them there and stirred a passion in them. We’re all part of this web, and our actions – no matter how small – are felt by others.”