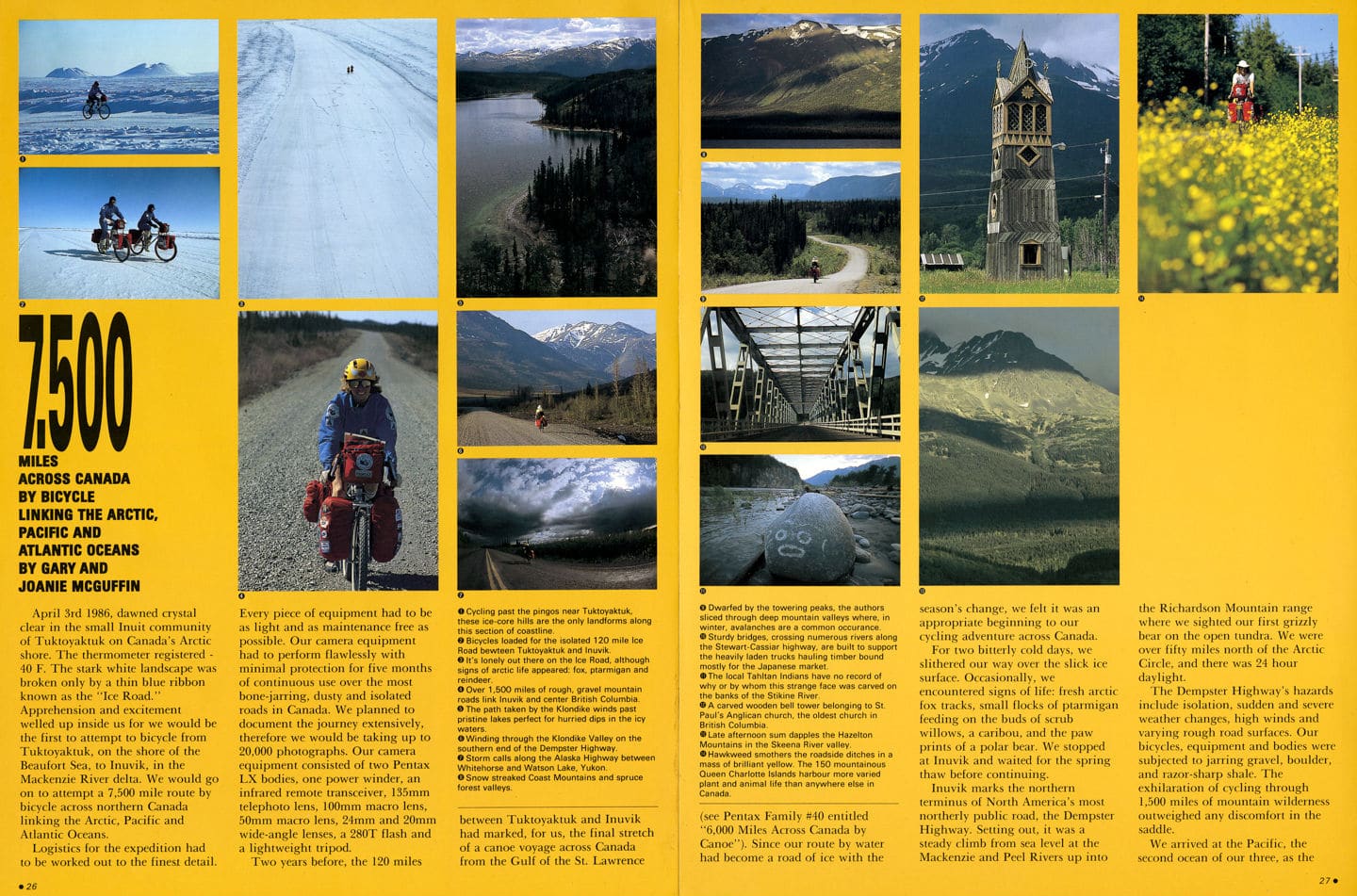

7,500 Miles Across Canada By Bicycle Linking The Arctic, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans

By Gary and Joanie McGuffin

April 3rd 1986, dawned crystal clear in the small Inuit community of Tuktoyaktuk on Canada’s Arctic shore. The thermometer registered – 40 F. The stark white landscape was broken only by a thin blue ribbon known as the “Ice Road.”

Apprehension and excitement welled up inside us for we would be the first to attempt to bicycle from Tuktoyaktuk, on the shore of the Beaufort Sea, to Inuvik, in the Mackenzie River delta. We would go on a attempt a 7,500 mile route by bicycle across northern Canada linking the Arctic, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Logistics for the expedition had to be worked out to the finest detail. Every piece of equipment had to be as light and as maintenance free as possible. Our camera equipment had to perform flawlessly with minimal protection for five months of continuous use over the most bone-jarring, dusty and isolated roads in Canada. We planned to document the journey extensively, therefore we would be taking up to 20,000 photographs. Our camera equipment consisted of two Pentax LX bodies, one power winder, an infrared remote transceiver, 135mm telephoto lens, 100mm macro lens, 50mm macro lens, 24mm and 20mm wide-angle lenses, a 280T flash and a lightweight tripod.

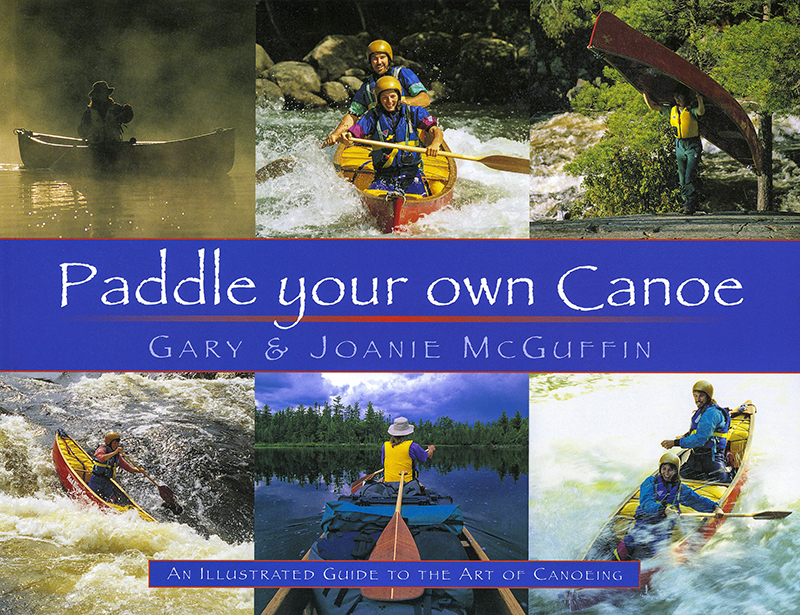

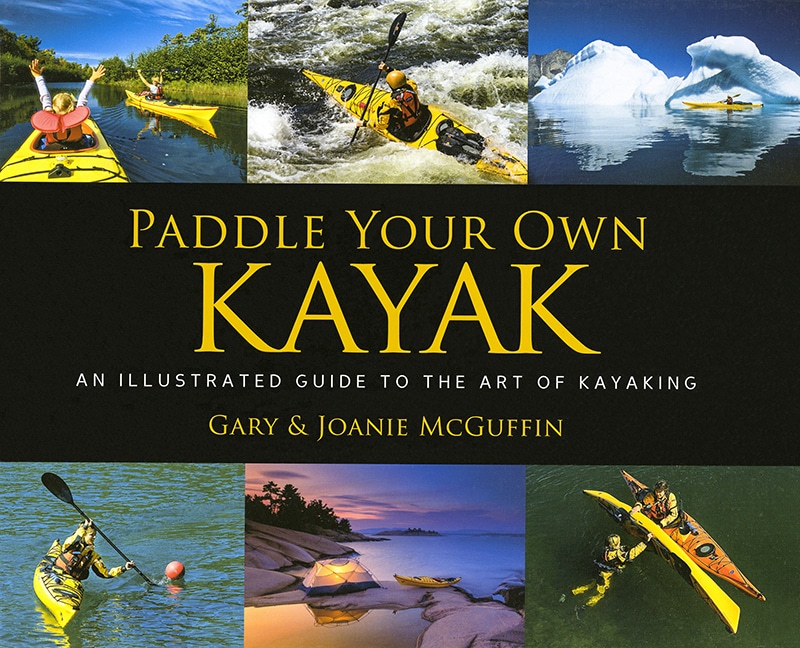

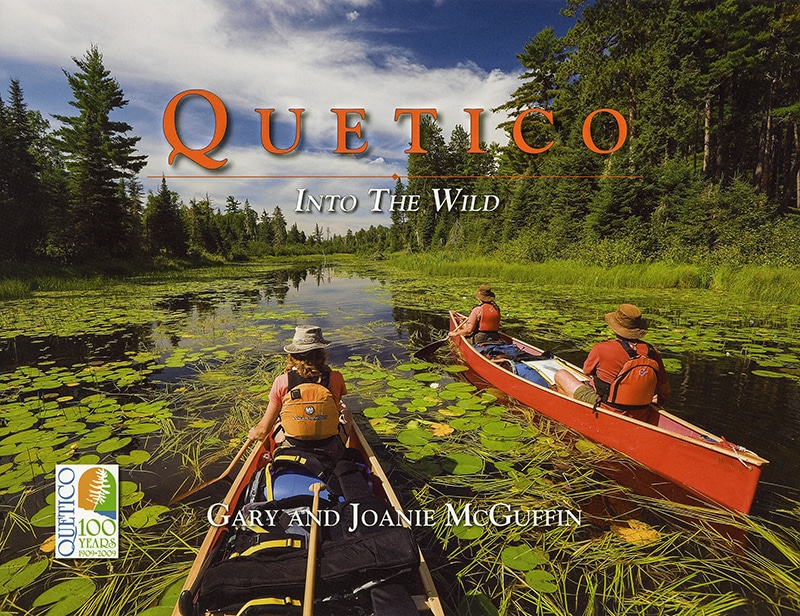

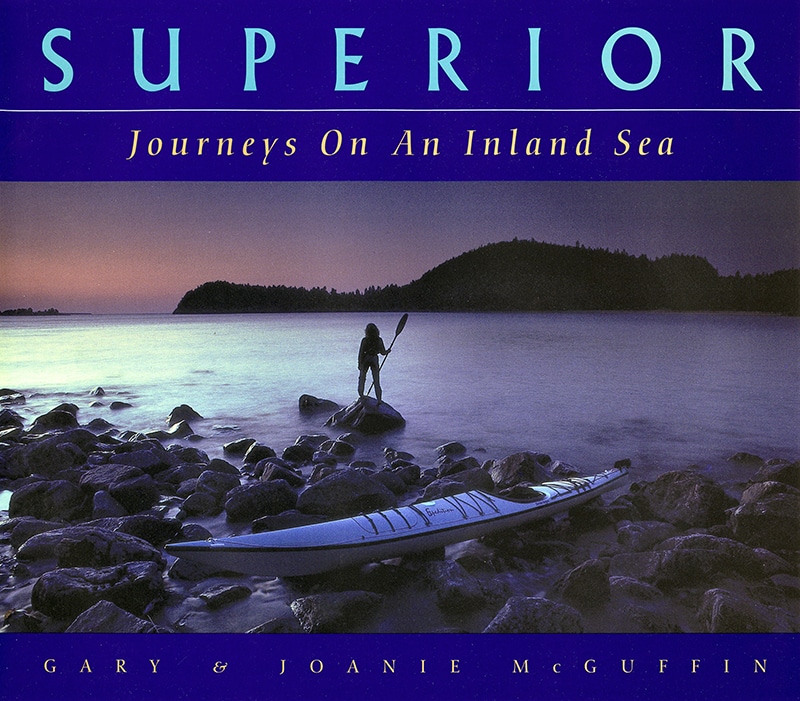

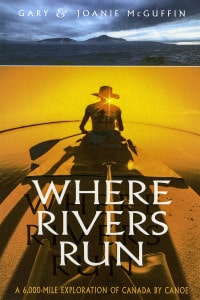

Two years before, the 120 miles between Tuktoyaktuk and Inuvik had marked, for us, the final stretch of a canoe voyage across Canada from the Gulf of the St. Lawrence (see Pentax Family #40 entitled “6,000 Miles Across Canada by Canoe”). Since our route by water had become a road of ice with the season’s change, we felt it was an appropriate beginning to our cycling adventure across Canada.

For two bitterly cold days, we slithered our way over the slick ice surface. Occasionally, we encountered signs of life: fresh arctic fox tracks, small flocks of ptarmigan feeding on the buds of scrub willows, a caribou, and the paw prints of a polar bear. We stopped at Inuvik and waited for the spring thaw before continuing.

Inuvik marks the northern terminus of North America’s most northerly public road, the Dempster Highway. Setting out, it was a steady climb from sea level at the Mackenzie and Peel Rivers up into the Richardson Mountain range where we sighted our first grizzly bear on the open tundra. We were over fifty miles north of the Arctic Circle, and there was 24 hour daylight.

The Dempster Highway’s hazards include isolation, sudden and severe weather changes, high winds and varying rough road surfaces. Our bicycles, equipment and bodies were subjected to jarring gravel, boulder, and razor-sharp shale. The exhilaration of cycling through 1,500 miles of mountain wilderness outweighed any discomfort in the saddle.

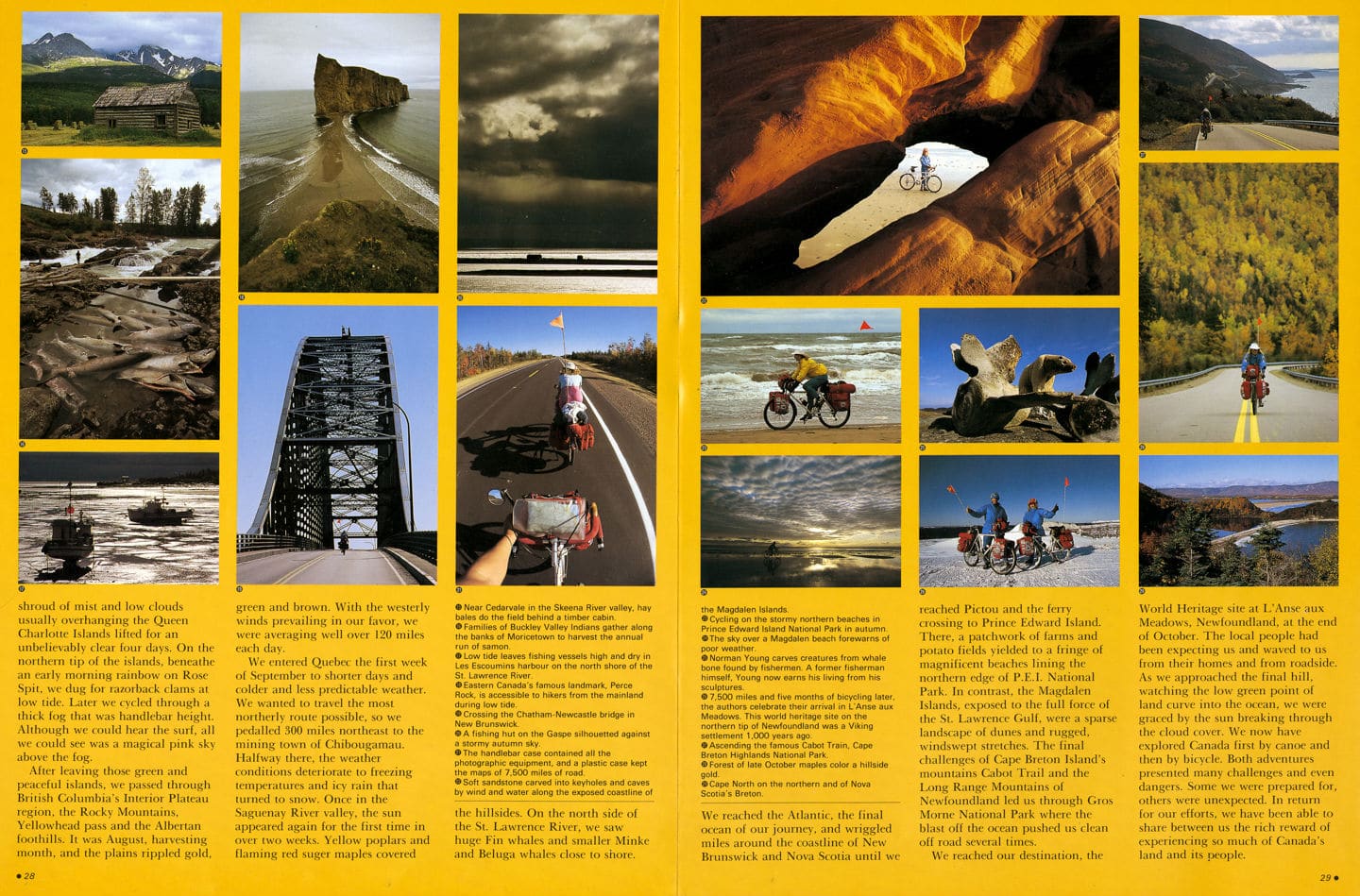

We arrived at the Pacific, the second ocean of our three, as the shroud of mist and low clouds usually overhanging the Queen Charlotte Islands lifted for an unbelievably clear four days. On the northern tip of the islands, beneath an early morning rainbow on Rose Spit, we dug for razorback clams at low tide. Later we cycled through a thick fog that was handlebar height. Although we could hear the surf, all we could see was a magical pink sky above the fog.

After leaving those green and peaceful islands, we passed through British Columbia’s Interior Plateau region, the Rocky Mountains, Yellowhead pass and the Albertan foothills. It was August, harvesting month, and the plains rippled gold, green and brown. With the westerly winds prevailing in our favor, we were averaging well over 120 mile each day.

We entered Quebec the first week of September to shorter days and colder and less predictable weather. We wanted to travel the most northerly route possible, so we pedalled 300 miles northeast to the mining town of Chibougamau.

Halfway there, the weather conditions deteriorate to freezing temperatures and icy rain that turned to snow. Once in the Saguenay River valley, the sun appeared again for the first time in over two weeks. Yellow poplars and flaming red suger maples covered the hillsides. On the north side of the St. Lawrence River, we saw huge Fin whales and smaller Minke and Beluga whales close to shore.

We reached the Atlantic, the final ocean of our journey, and wriggled miles around the coastline of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia until we reached Pictou and the ferry crossing to Prince Edward Island. There, a patchwork of farms and potato fields yielded to a fringe of magnificent beaches lining the northern edge of P.E.I. National Park. In contrast, the Magdalen Islands, exposed to the full force of the St. Lawrence Gulf, were a sparse landscape of dunes and rugged, windswept stretches. The final challenges of Cape Breton Island’s mountains Cabot Trail and the Long Range Mountains of Newfoundland led us through Gros Morne National Park where the blast off the ocean pushed us clean off road several times.

We reached our destination, the World Heritage site at L’Anse aux Meadows. Newfoundland, at the end of October. The local people had been expecting us and waved to us from their homes and from roadside. As we approached the final hill, watching the low green point of land curve into the ocean, we were graced by the sun breaking through the cloud cover. We now have explored Canada first by canoe and then by bicycle. Both adventures presented many challenges and even dangers. Some we were prepared for, others were unexpected. In return for our efforts, we have been able to share between us the rich reward of experiencing so much of Canada’s land and its people.