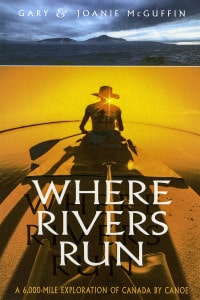

Landscape of my dreams

By Joanie McGuffin

Article in Reader’s Digest

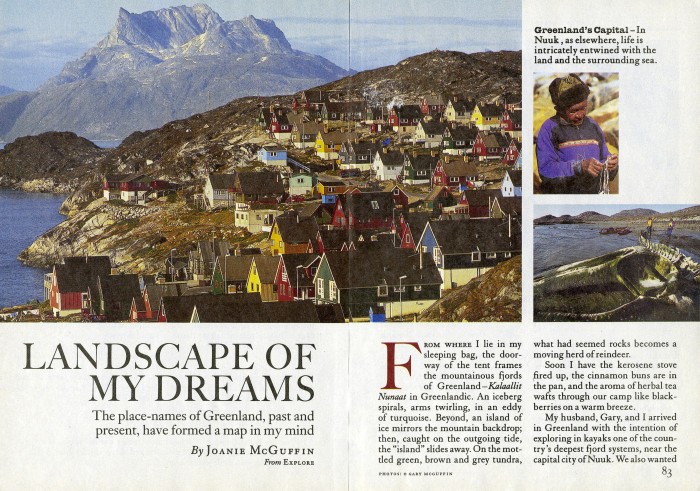

From where I lie in my sleeping bag, the doorway of the tent frames the mountainous fjords of Greenland – Kaballis Numaar in Greenlandic. An iceberg spirals, arms twirling, in an eddy of turquoise. Beyond, an island of ice mirrors the mountain backdrops; then, caught on the outgoing tide, the “island” slides away. On the mottled green, brown and grey tundra, what had seemed rocks becomes a moving herd of reindeer.

From where I lie in my sleeping bag, the doorway of the tent frames the mountainous fjords of Greenland – Kaballis Numaar in Greenlandic. An iceberg spirals, arms twirling, in an eddy of turquoise. Beyond, an island of ice mirrors the mountain backdrops; then, caught on the outgoing tide, the “island” slides away. On the mottled green, brown and grey tundra, what had seemed rocks becomes a moving herd of reindeer.

Soon I have the kerosene stove fired up, the cinnamon buns are in the pan, and the aroma of herbal tea wafts through our camp like blackberries on a warm breeze.

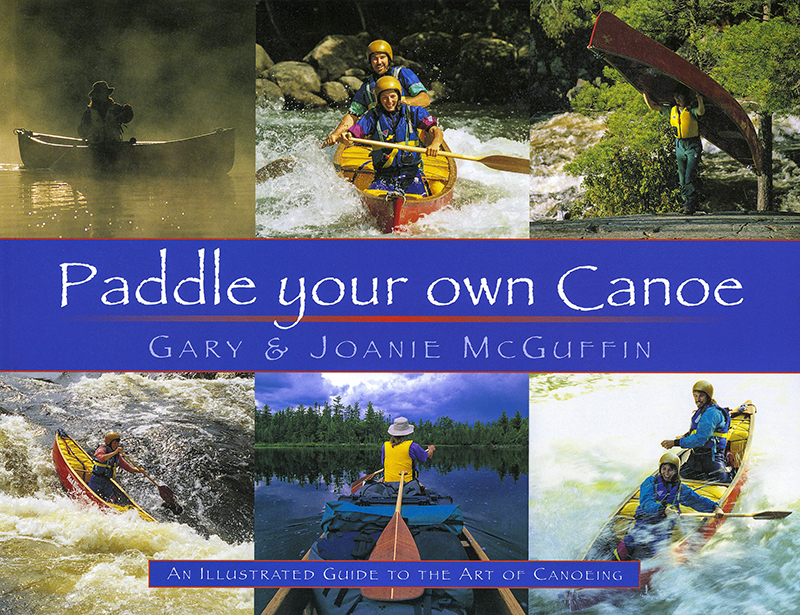

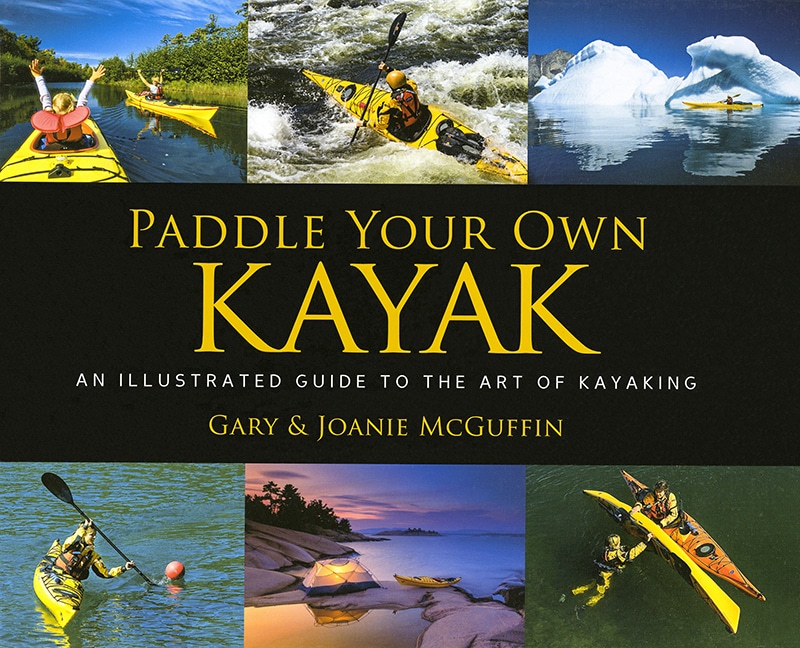

My husband, Gary, and I arrived in Greenland with the intention of exploring in kayaks one of the country’s deepest fjord systems, near the capital city of Nuuk. We also wanted to backpack overland between settlements past and present, especially the abandoned. Norse settlements that began with Erik the Red’s arrival in 985.

Travelling with us are three Greenlandic friends, Valdemar Geisler, his brother, Nukannguaq, and Frederik, a former policeman in Nuuk. There’s not a lot of talk as they amble along, listening with good humour as we try to get our Canadian tongues around the Greenlandic words.

For five days we walk the 80 kilometres from Quarqut to Kapitillit, following old reindeer trails. (Villages strung along this rugged coast are generally accessible to one another only by air or boat.) Then, at the top of the last ridge before the sea, Gary signals me to drop low.

I wriggle, snakelike, to where the others lie on a bed of spongy heath. No one speaks as Frederik points and Nukanmguaq grins. The reindeer are moving our way, unaware of our presence. Calves, cows and bulls. From where I lie, I estimate at least a hundred animals.

As the lines of reindeer flow up the slope towards us, there is the clatter of hooves on rock, the sound of their breathing and snorting, calves bawling. A cow and calf are so close I clearly see their liquid black eyes, their fur tufted and moulting, their splayed hooves so perfectly adapted for uneven terrain.

Soon a big bull senses our presence. His snort scatters the others, but, drawn by curiosity, they return, Gary clicks the camera shutter; the calves bound off, then trickle back. We play this game for awhile until the reindeer go.

Soon a big bull senses our presence. His snort scatters the others, but, drawn by curiosity, they return, Gary clicks the camera shutter; the calves bound off, then trickle back. We play this game for awhile until the reindeer go.

We camp near Sandnes, a Norse settlement that dates back a thousand years. About 1,000 people lived here on some 90 farms. We walk along the stone-and-sod walls so clearly outlining the ruins of a farmstead. With the help of a detailed map, we easily locate the cowshed, stables, a smithy and the longhouse.

The Norse settlers who lived here originated with the arrival of Erik the Red, the explorer who gave Greenland its enticing name. Icelandic farmers arrived with their horses, sheep, and cattle. But try as they might, in only a few hundred years, these early settlers disappeared, defeated by a combination of harsh winters and poor summers, crop failures and sickness.

The land returned to the Thule, Greenland’s final wave in a succession of Artic peoples that began almost 5,000 years ago. Their use of skins rather than woven cloth, and hide-covered sea kayaks and uminaks rather than great oak-timbered ships, made them far better adapted to the climate and terrain.

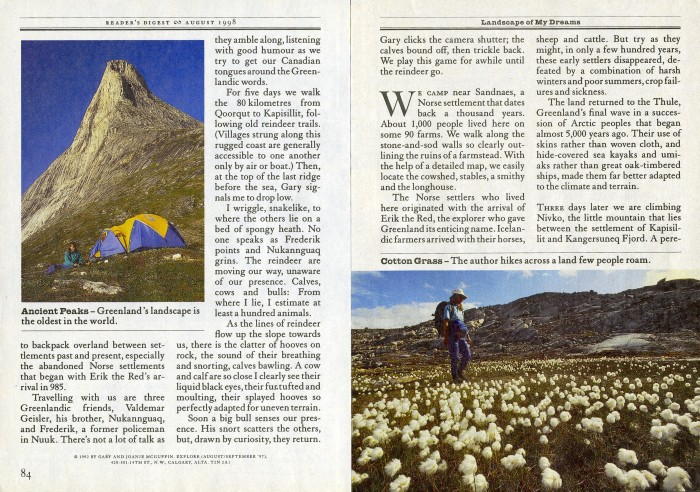

Three days later we are climbing Niwko, the little mountain that lies between the settlement of Kapiillit and Kangersuneq Fjord. A peregrine falcon swoops down from the cliffs lining one side of the valley. Few birds actually stay year-round, except ravens and the magnificent white-tailed eagles indigenous to Greenland. We hike through fields of cotton grass and harebells and rock – three-billion-year-old bed-rock. Greenland’s landscape is the oldest in the world.

From the top of Nivko, we can see out across the ice cap, which stretches 500 kilometres across to the other side of Greenland. In this world of ice, mountains are buried, with only their summits protruding. From where we stand we can see where the ice that chokes Kangeriuneq Fjord is born. It appears to flow off the glacier, but in slow motion, imperceptible to us.

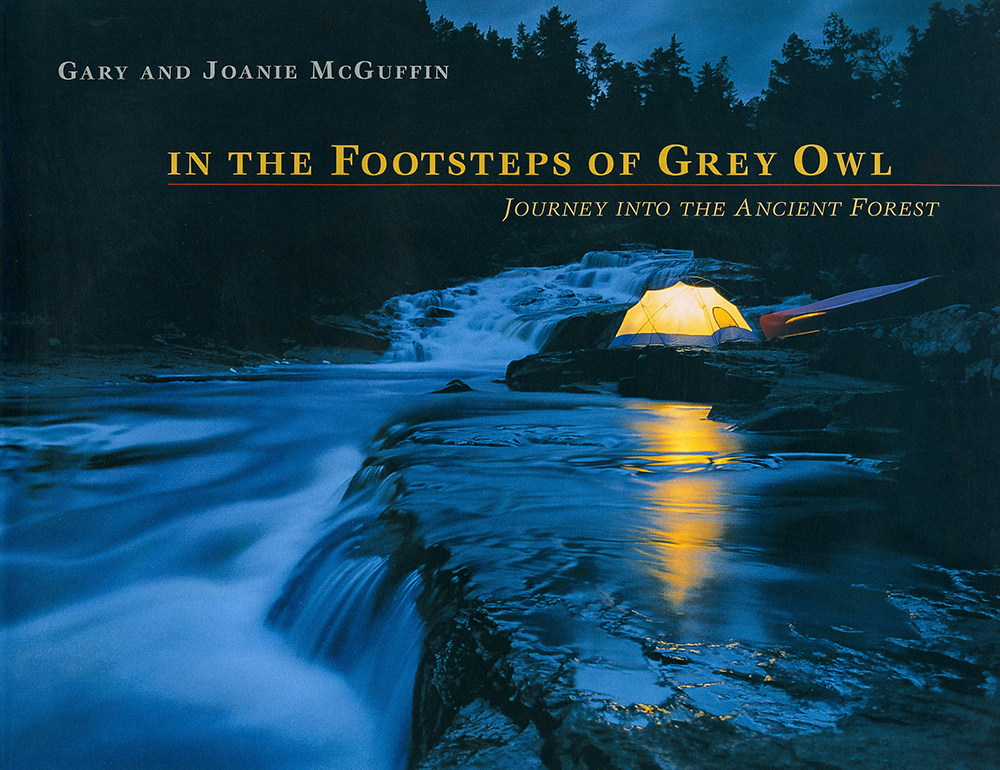

In the land of the midnight sun, the length of day has no bearing on when you stop to set up camp; we push on until we’re tired. Camping is mostly a matter of finding freshwater, and with all the rivers running down from the glaciers that’s hardly ever a problem. Because so few people roam this land and the animals are not familiar with human food, we never worry about scavengers.

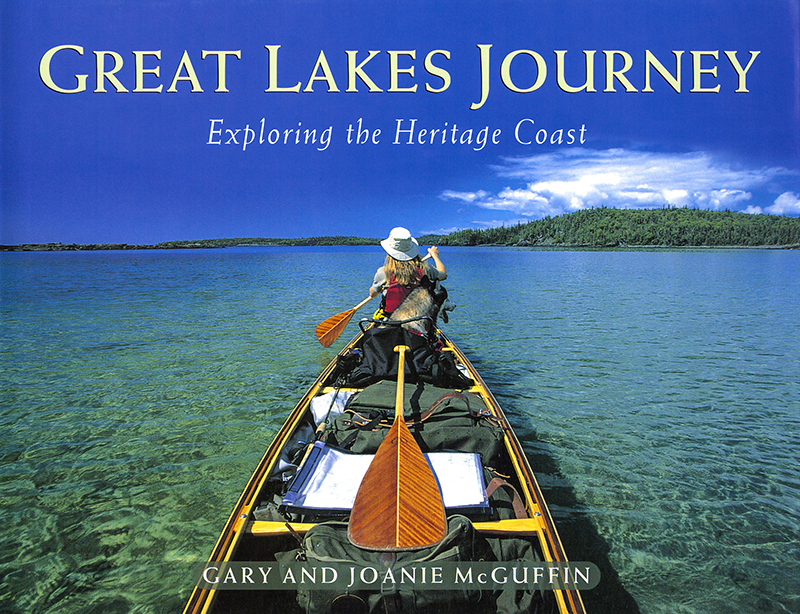

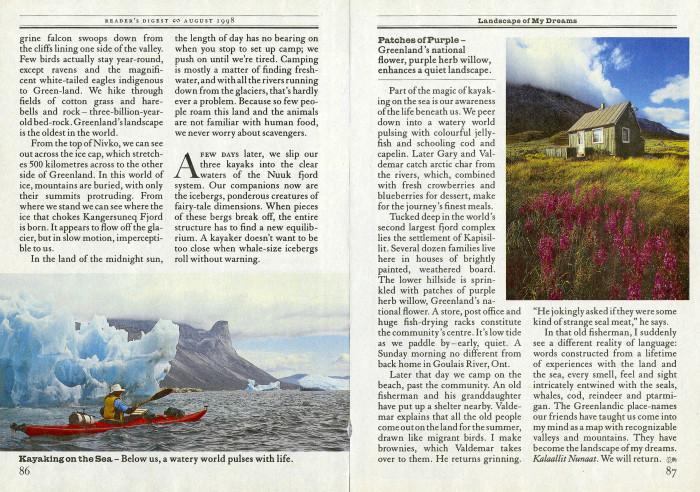

A few days later we slip our three kayaks into the clear waters of the Nuuk fjord system. Our companions now are the icebergs, ponderous creatures of fairy-tale dimensions. When pieces of these bergs break off, the entire structure has to find a new equilibrium. A kayaker doesn’t want to be too close when whale-size icebergs roll without warning.

Part of the magic of kayaking on the sea is our awareness of the life beneath us. We peer down into a watery world pulsing with colourful jellyfish and schooling cod and capelin. Later Gary and Valdemar catch arctic char from the rivers, which, combined with fresh crowberries and blueberries for dessert, make for the journey’s finest meals.

Part of the magic of kayaking on the sea is our awareness of the life beneath us. We peer down into a watery world pulsing with colourful jellyfish and schooling cod and capelin. Later Gary and Valdemar catch arctic char from the rivers, which, combined with fresh crowberries and blueberries for dessert, make for the journey’s finest meals.

Tucked deep in the world’s second largest fjord complex lies the settlement of Kapiullit. Several dozen families live here in houses of brightly painted, weathered board. The lower hillside is sprinkled with patches of purple herb willow, Greenland’s national flower. A store, post office and huge fish-drying racks constitute the community’ centre. It’s low tide as we paddle by – early, quiet. A Sunday morning no different from back home in Goulais River, Ont.

Later that day we camp on the beach, past the community. An old fisherman and his granddaughter have put up a shelter nearby, Valdermar explains that all the old people come out on the land for the summer, drawn like migrant birds. I make brownies, which Valdemar takes over to them. He returns grinning. “He jokingly asked if they were some kind of strange seal meat,” he says.

In that old fisherman, I suddenly see a different reality of language: words constructed from a lifetime of experiences with the land and the sea, every smell, feel and sight intricately entwined with the seals, whales, cod, reindeer and ptarmigan. The Greenlandic place names of friends have taught us come into my mind as a map with recognizable valleys and mountains. They have become the landscape of my dreams. Kalaallit Nuvaat. We will return.