Ancient Waterways : Protecting Lands for Life

A Journey from Algonquin to Algoma Highlands

Written by Joanie McGuffin

My eyes went from the computer’s eerie glow to the dark night sky where a billion pricks of light illuminated faraway worlds. I recognized a few of the traveling stars as satellites and wondered which one was receiving our signal. It took twenty minutes to an hour for our typed stories and photographs to travel 25,000 miles above the earth and down to a receiving dish in Ottawa. From there, the information entered the phone lines and ended up at our webmaster’s computer in Sault Ste. Marie. Then, the files traveled to the web and finally landed in the newspaper. Once weekly, newspaper presses across Canada rolled out a color page in the Saturday edition to be read with the morning coffee. My husband Gary’s and my reports were being followed by our readers, while we traveled along Ontario’s Ancient Forest Water Trail. We progressed to the cadence of Nature’s moving water and communicated at the same time with people thousands of miles away, thanks to the power of the sun and the high tech world of telecommunications.

My eyes went from the computer’s eerie glow to the dark night sky where a billion pricks of light illuminated faraway worlds. I recognized a few of the traveling stars as satellites and wondered which one was receiving our signal. It took twenty minutes to an hour for our typed stories and photographs to travel 25,000 miles above the earth and down to a receiving dish in Ottawa. From there, the information entered the phone lines and ended up at our webmaster’s computer in Sault Ste. Marie. Then, the files traveled to the web and finally landed in the newspaper. Once weekly, newspaper presses across Canada rolled out a color page in the Saturday edition to be read with the morning coffee. My husband Gary’s and my reports were being followed by our readers, while we traveled along Ontario’s Ancient Forest Water Trail. We progressed to the cadence of Nature’s moving water and communicated at the same time with people thousands of miles away, thanks to the power of the sun and the high tech world of telecommunications.

A long canoe trip is thrilling — it becomes a way of life that connects us with meaningful perceptions of time not measured by clocks and calendars. The span of daylight, the extent of darkness, and an awareness of changing seasons become our timepieces. Each evening’s campsite is a discovery, and although our stay is short, these homes become more indelibly imprinted on us than the houses we leave behind. We hope the stories of our adventures along the Ancient Forest Water Trail that we beamed back to the newspaper, radio and our Website have imparted the importance of protecting larger landscapes and corridors, so we can continue to feel the thrills and meaningfulness of wilderness.

We began planning our ancient forest canoe journey through Ontario at the same time the provincial government launched a massive land-use planning process, Lands for Life, which would determine the fate of close to half of Ontario’s public lands. The Lands for Life process, for better or for worse, would complete the park system by the Year 2000. A series of Round Tables traveling around the province gathered input at public meetings, requesting imaginative ideas to deal with the conflicting uses of industry and tourism. The forest and mining industries attitude of the land base as a vast inexhaustible storehouse of resources are a deeply entrenched view that had to budge. Ontario’s shrinking wilderness was in dire trouble, and desperately needed an ecologically sound approach to protect it.

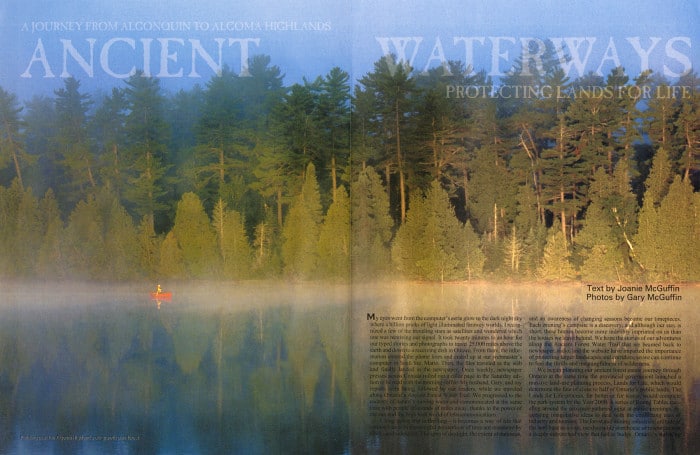

We mapped a 1200-mile, three-month canoe route across a corridor containing islands of ancient forest The route linked several well-known canoeing destinations, such as Algonquin Provincial Park, Temagami’s Lady Evelyn Smoothwater wilderness, the Spanish and Mississagi Rivers and Lake Superior.

Five rivers drew us upstream and inland from the Lake Superior shoreline, where we circumnavigated the world’s largest expanse of freshwater. Four rivers flow west and southwest originating in the Algoma Highlands and end their journey on Lake Superior’s eastern shore The Aubinadong-Mississagi also springs from the forested headwaters, but meanders southward to merge with Lake Huron.

Our extended journey gave us a sense of the broad expanse needed by large mammals for survival. We imagined ourselves having to survive — find food, a mate, bear young, and raise them all within the confines of the island we camped on — it would be impossible. The same is true for many creatures whose protected habitats are small and ringed with roads and cleared land.

Prior to our trip, Gary saw an area of green divided only by its waterways, and wondered if this would be like the big pine forests of his childhood in Temagami. Our first canoe trip into the Algoma Highlands wa sin mid-May. The ice had only just vanished and the spring green of tiny buds and baby leaves cast a fresh-as-new-life spell on us. Moose and black bear tracks pressed into the highwater mark’s soft mudflats. Narrow creeks and bubbling streams joining quiet lakes danced with speckled trout.

Ancient cedar spiraled out from shore like unicorn horns and giant white pine embraced the lakeshore, rising all the way to the ridge tops. Arriving in the middle of one small lake, we spun our canoe 360 degrees. The blur of giant tree trunks and feathered limbs catching bits of sky encircled us like dancers. Connections to a distant past deepened as we paddled further north to the top of the Aubinadong River headwaters. Portage blazes marked old footpaths that had been used most recently by a large wolf. The moss grew in thick carpets along huge nursery logs. Tiny seedlings sprouted up amongst mushrooms and flowering vines. The only thing that broke the spell of paradis found was the anxious feeling of paradise lost.

Giant white pine, once a plentiful and valued timber, is now rare and even more valued. After several trips in various seasons through the Highlands, we were convinced that without protection, it was only a matter of time before roads would be built, the pine trees cut, and the magic of this magnificent place lost forever.

Giant white pine, once a plentiful and valued timber, is now rare and even more valued. After several trips in various seasons through the Highlands, we were convinced that without protection, it was only a matter of time before roads would be built, the pine trees cut, and the magic of this magnificent place lost forever.

The timing for our journey could not have been better. In a letter to World Wildlife Fund Canada, Ontario’s Premier Mike Harris made a commitment “to the completion of parks and other natural heritage areas representing the full spectrum of the province’s natural features and ecosystems.” This promise, if left unfulfilled, would mock the agreement signed in 1989 by Canada’s Prime Minister, the ten provincial premiers, and two territorial leaders. WWF Canada’s Endangered Spaces goal with this agreement was to campaign and help ensure that all of Canada’s natural regions would be represented by a network of protected areas by the year 2000. With barely three years to go, progress had been dismally slow.

Lands for Life represented the last opportunity for Ontario to create large new parks, protected areas, and connecting corridors for the survival of many plants and animals. Three of the province’s larger conservation organizations (World Wildlife Fund Canada, the Federation of Ontario Naturalists, and the Wildlands League) banded together to form the Partnership for Public Lands. They addressed a broad range of goals beyond the creation of parks and protected areas such as preserving the ecological integrity of all public lands for the long term.

Old growth forest landscapes, healthy waterways, clean air, and the preservation of species diversity and habitat on a landscape level are essential for healthy human communities and indeed the very survival of our species.

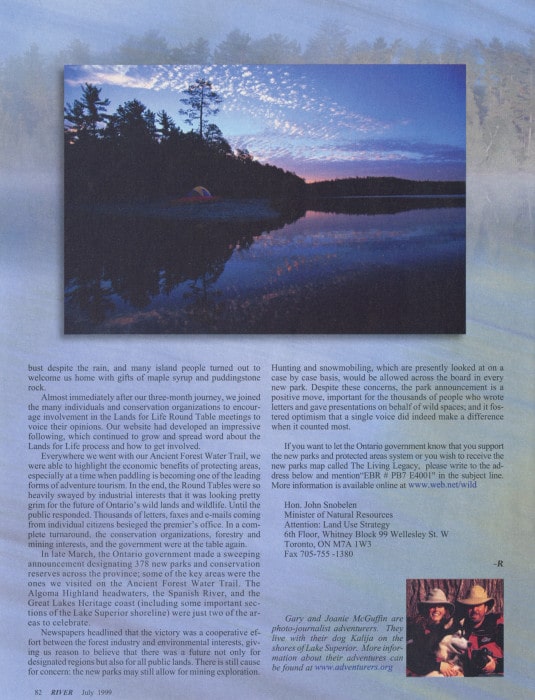

Paddling the route was only one part of the adventure. In order for the journey to have any immediate impact on decisions affecting Ontario’s future, it was absolutely crucial to communicate the story en route. In three months of paddling, we wanted to reveal the forest’s story as we experienced it, communicating from the wilderness waterways rather than waiting until we returned home.

With power from the sun, we charged a 12-volt battery, which in turn powered the rest of the equipment and allowed us to transmit stories and photographs to a website, and produce a weekly colour page for Southam News (a national newspaper chain of 57 papers). We kept in weekly contact by voice with our national radio network, CBC, and arranged meetings with a Baton Broadcasting film crew who documented the journey for the 13-part Down To Earth series.

Our weekly 15 minute radio reports were as easy as if the telephone were plugged into a pine tree. The satellite dish was in the lid of the phone. All we needed for communication was an unimpeded view toward the southwestern sky. Occasionally we had added excitement. Oce, a black bear swam toward the island from where I was transmitting. Another time, the sound of snorting and snuffling otters carried over the lines to people gathered around their radios. Each morning, we gave thanks to the sun for its energy — and for its ability to beam off the solar panels sitting on the canoe’s deck, charging the battery every day.

The idea for a journey to help save these forests was born not only from our love for the forest that had shaped our lives, but also from the scientific studies of Peter Quimby and Tom Lee, and their research on ancient forests.

The idea for a journey to help save these forests was born not only from our love for the forest that had shaped our lives, but also from the scientific studies of Peter Quimby and Tom Lee, and their research on ancient forests.

Our paths crossed with Peter and Tom in Temagami. Earth Watch volunteers from around the world were assisting them in a study of North America’s remaining Great Lakes-St. Lawrence ancient forest landscapes. They agreed that wider public appreciation for the rarity of these forests was essential to help protect what little remained. Two hundred years ago, a squirrel could travel from the Maritimes to the Mississippi, north to Lake Superior, or south to the New England Appalachians without ever touching the forest floor. Today, less than one percent of that original forest remains, in pockets along the corridor between the Ottawa River Valley and Lake Superior.

By late spring, we were ready to depart from Algonquin Provincial Park’s Canoe Lake. A straightforward route (paddled by canoeists from around the world every summer) led us north through the park to the Amable du fond River. The park’s popularity necessitates having a park itinerary and booking each night’s campsite prior to departure. Although we were early in the season and saw no one, the scheduling was a definite departure from our usual freedom on northern Ontario’s wild waterways. Nightly we answered wolf howls and called barred owls to us. We paddled to the sound of frog choruses, through moose meadows where we never failed to see two or three velvet antlered bulls and a cow moose with calves. Archeological research prior to the journey helped us choose portions of our route , such as the historic Amable du Fond, the old fur trade route of the Mattawa, and Ottawa Rivers leading to Temagami.

Within the 4,000 square mile region of Temagami, a web of waterway routes and land trails, or Nastawgan, represents one of North America’s great system of interconnected canoe routes. Finding stone tools along the sandspits of our campsites and paintings on rock walls reminds us of the history of people dating back more than 6,000 years. When Alex Mathias, a Teme-augama Anishnabai elder, met us on Obabika Lake, we spent a day learning about the spiritual significance of the n’Daki-menan, the traditional family hunting grounds.

Mathias appreciates spending time with interested travelers. When we later paddled to the base of Maple Mountain, we were able to recognize it as more than Ontario’s second highest point of land. It is known as cheebaigin [gee-bay-jin], “the place where the spirits go. “ It was once tribal tradition to lay bodies, after death, at the foot of the mountain. Day-to-day canoeing is being able to see more than what’s obvious, and understanding the relationship of all people to the land for generations past, present, and future.

Peter Quimby had studied this area and the Partnership for Public Lands was advocating its protection. White Owl Lake and Bark Lake along the Mississagi River Waterway contrasted in their pristine nature with the façade of green that we sometimes experienced where clearcuts abutted the water’s edge. We encountered a stark contrast on a lake as we left Lady Evelyn Wilderness. On one shore an incredibly complex diversity of insects, plants, animals and tree species were co-existing from the soil to the forest canopy. On the opposite shore, stood an ecologically and economically impoverished clearcut landscape where only two pine seed trees remained and popular seedlings sprouted from the barren earth. In some places we heard the logging machinery working around the clock.

The Aubinadong and its west branch to Megisan, Gord, and Lance Lakes marked the last upstream leg of our journey to Lake Superior. Low water levels had left West Aubinadong looking more lake a black cobble laneway than a river. A steady rain soaked the lichen-covered rocks, creating footing as sketchy as greased ball bearings. At day’s end, when a barred owl swooped across our path near a spit of sand and mud pockmarked with moose and timber wolf tracks, we decided it was time to camp. Between showers, we put up the tent and threw our belongings inside.

Without thinking, I slung my sleeping bag to Gary like a football. It went straight up and over his head, bouncing off the tent roof and into the river. Launching myself off the bank, I grabbed it – realizing belatedly that I was now firmly planted in ankle-deep mud. Gary joined in my laughter. A fitting end to a 10-hour day where we made only four miles of progress.

We could have ended our journey in the Algoma Highlands; after all, it was the place that gave us the hope and inspiration to set off in the first place. We paddled slowly, savoring each lake, river, creek, and campsite – knowing that the fate of the big pines and the surrounding wilderness was precarious. Would enough people know and care?

As we neared the end of our journey, Lake Superior came into view after our paddle down Farewell Creek, the Cow, and the Montreal River. It was a serene day and Montreal Island floated like a cloud in gray skies with only the horizon line anchoring it to the water. We traveled a hundred miles further south on Lake Superior’s shoreline to reach St. Mary’s River, and the route to St. Joseph’s Island. An entourage of paddlers dressed in voyageur costumes paddled the final miles to historic Fort St. Joseph in their voyageur canoes. Spirits were robust despite the rain, and many island people turned out to welcome us home with gifts of maple syrup and puddingstone rock.

As we neared the end of our journey, Lake Superior came into view after our paddle down Farewell Creek, the Cow, and the Montreal River. It was a serene day and Montreal Island floated like a cloud in gray skies with only the horizon line anchoring it to the water. We traveled a hundred miles further south on Lake Superior’s shoreline to reach St. Mary’s River, and the route to St. Joseph’s Island. An entourage of paddlers dressed in voyageur costumes paddled the final miles to historic Fort St. Joseph in their voyageur canoes. Spirits were robust despite the rain, and many island people turned out to welcome us home with gifts of maple syrup and puddingstone rock.

Almost immediately after our three-month journey, we joined the many individuals and conservation organizations to encourage involvement in the Lands for Life Round Table meetings to voice their opinions. Our website had developed an impressive following, which continued to grow and spread the word about the Lands for Life process and how to get involved.

Everywhere we went with our Ancient Forest Water Trail, we were able to highlight the economic benefits of protecting areas, especially at a time when paddling is becoming one of the leading forms of adventure tourism. In the end, the Round Tables were so heavily swayed by industrial interests that it was looking pretty grim for the future of Ontario’s wild lands and wildlife. Until the public responded. Thousands of letters, faxes and emails coming from individual citizens besieged the Premier’s office. In a complete turnaround, the conservation organizations, forestry and mining interests, and the government were at the table again.

In late March, the Ontario government made a sweeping announcement designating 378 new parks and conservation reserves across the province; some of the key areas were the ones we visited on the Ancient Forest Water Trail. The Algoma Highland headwaters, the Spanish River, and the Great Lakes Heritage Coast (including some important sections of the Lake Superior shore) were just two of the areas to celebrate.

Newspapers headlined that the victory was a cooperative effort between the forest industry and environmental interests, giving us reason to believe that there was a future not only for designated regions but also for all public lands. There is still cause for concern; the new parks may still allow for mining exploration. Hunting and snowmobiling, where are presently looked at on a case by case basis, would be allowed across the board in every new park. Despite these concerns, the park announcement is a positive move, important for the thousands of people who wrote letters and gave presentations on behalf of wild spaces; and it fostered optimism that a single voice did indeed make a difference when it counted most.

If you want to let the Ontario government know that you support the new parks and protected areas system or you wish to receive the new parks map called The Living Legacy, please write to the address below and mention “EBR # PB7 E4001” in the subject line. More information is available online at www.web.net/wild

Hon. John Snobelen

Ministry of Natural Resources

Attention: Land Use Strategy

6th Floor, Whitney Block 99 Wellesley St. W

Toronto, ON M7A 1W3

FAX 705-75-1380

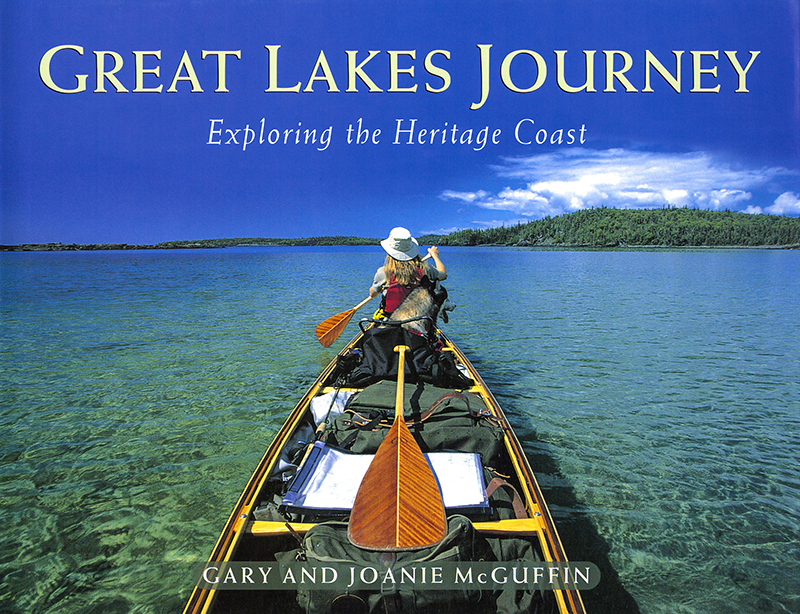

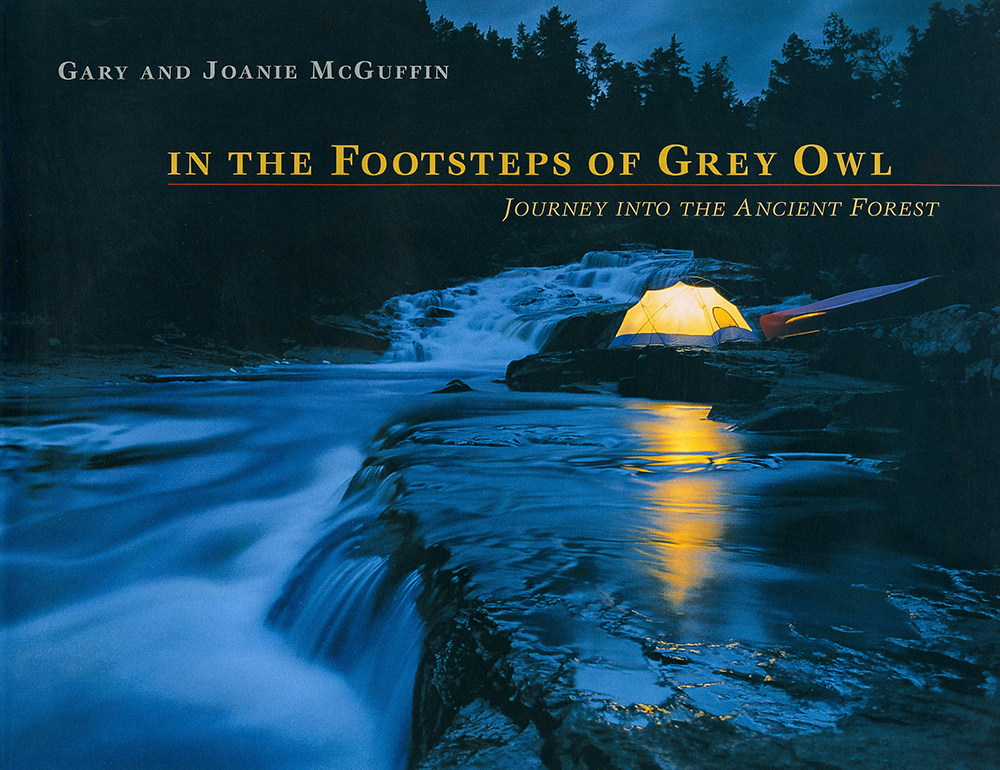

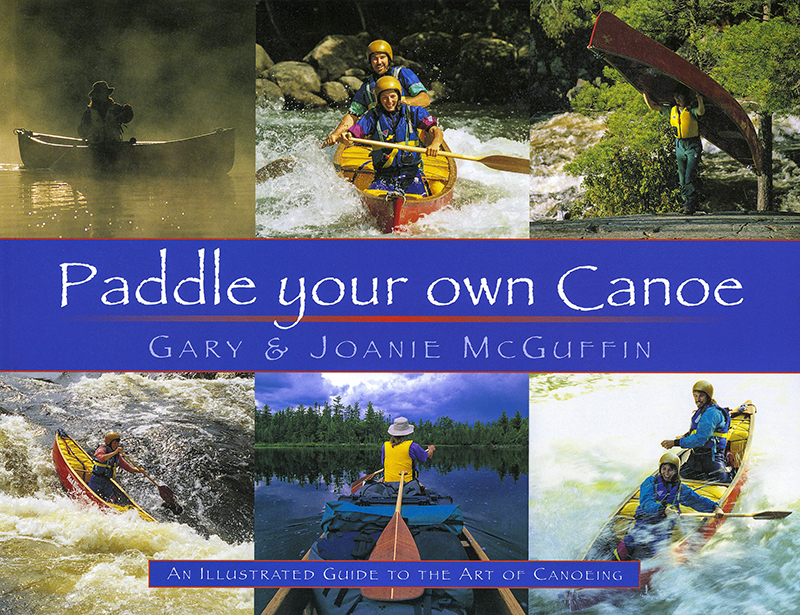

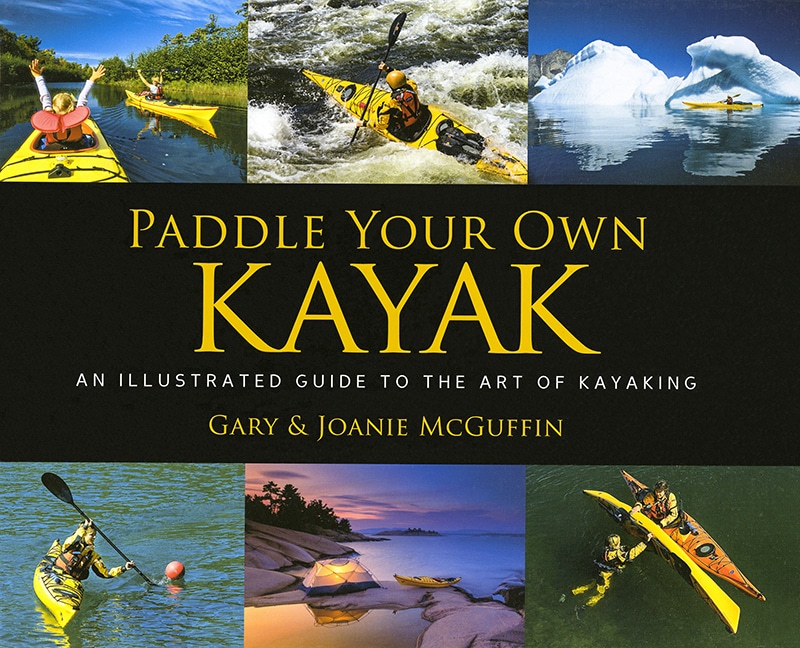

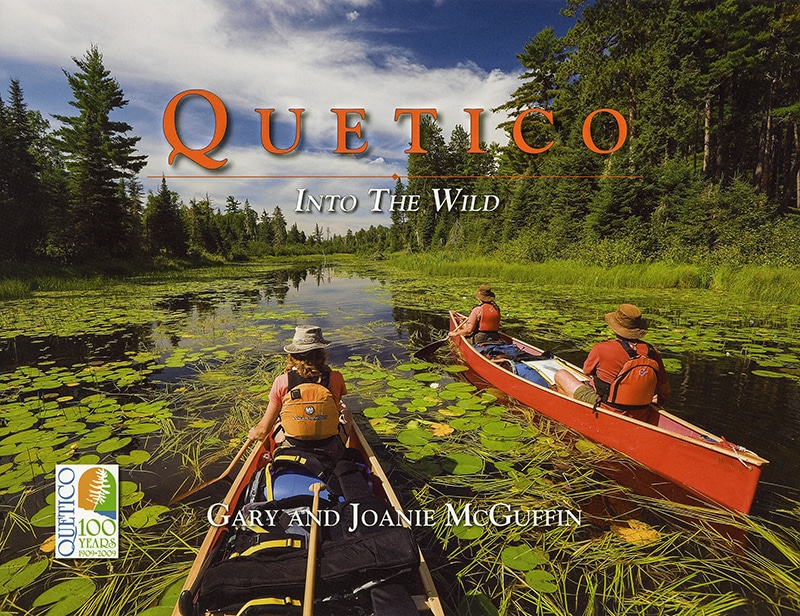

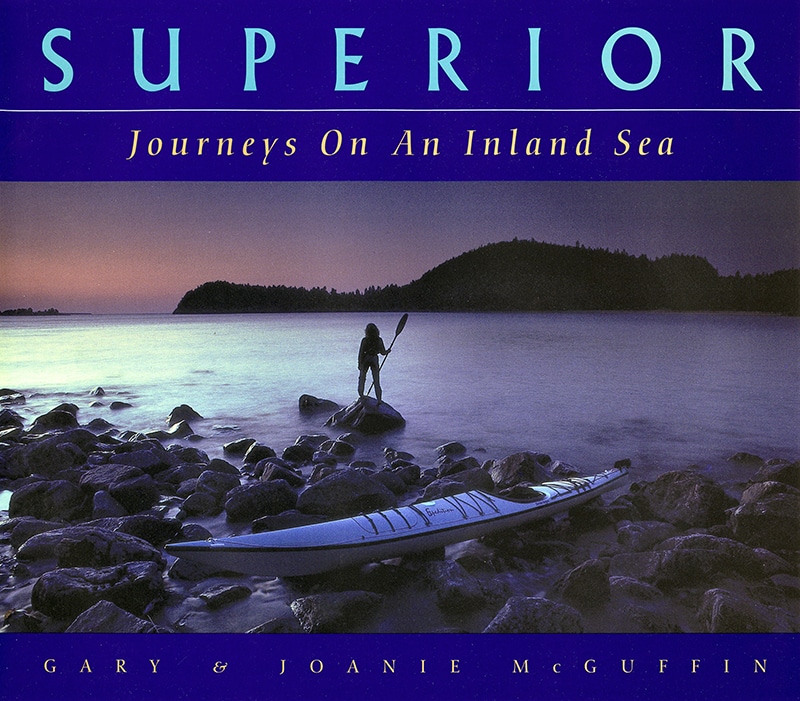

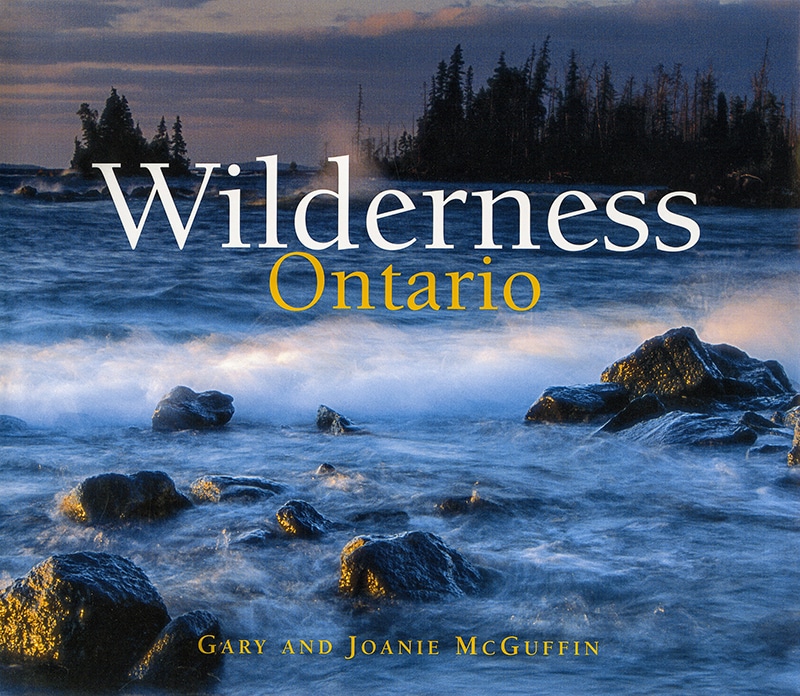

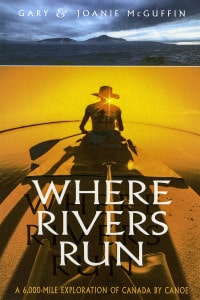

Gary and Joanie McGuffin are photo-journalist adventurers. They live with their dog Kalija on the shores of Lake Superior. More information about their adventures can be found at www.adventurers.org

Gary and Joanie McGuffin are photo-journalist adventurers. They live with their dog Kalija on the shores of Lake Superior. More information about their adventures can be found at www.adventurers.org

Captions on images:

[Joanie slogging through the muck] Joanie and Gary’s journey encompassed extensive overland portages. This muddy one was near the Wanapitei River.

[fall forest scene] The Algoma Highlands roll along the eastern edge of Lake Superior, just north of Sault Sainte Marie, Ontario. Ancient cedar and giant white pine rise from shorelines to ridge tops. Like many of North America’s remaining intact forest, the original trees of the Highlands risk extinction due to human encroachment and logging. A large part of the McGuffins’ trip was geared towards convincing the Ontario government to protect this ecologically rich area.

[Alex] The Temagami old growth forests are of deep spiritual significance to Alex Mathias, a Teme-augama Anishnabai elder. In his efforts to protect his traditional family hunting grounds. Mathias often speaks out in exhausting courtroom battles.

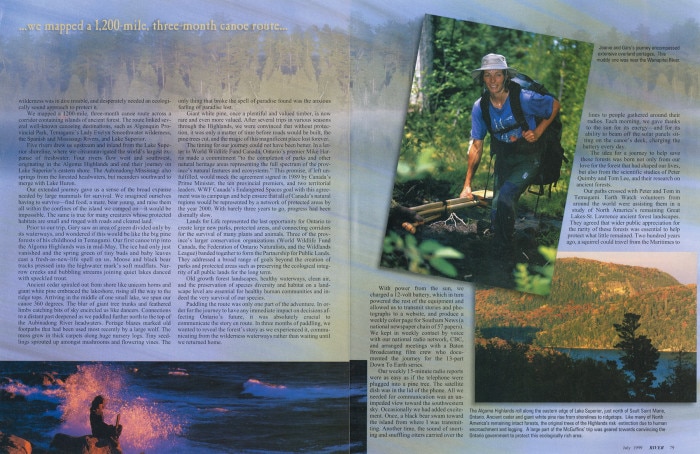

[McGuffins and technology]Technology in the most unexpected of places. Joanie and Gary display their portable, solar-powered, on-the-river office used to write articles, take photos, and to do daily updates on their website. Surrounding the McGuffins are articles they published while on their journey.