Art for Nature’s Sake

By Kate June-Friensen

Article in SMITHSONIAN, December 2006

(Continued from page 29)

This past September, seven artists clambered aboard canoes in the backwoods of Quebec for an 18-day, 140-mile river journey supported by the Smithsonian Institution to raise awareness of new threats to the continent’s largest uninterrupted forest. The boreal, or northern forest stretches more than two million square miles across Canada and into Alaska. It is home to nearly half of North America’s bird species, depending on the season. Scientist say the forest consumes so much atmospheric carbon dioxide and generates so much oxygen that, like the Amazon rain forest, it regulates the earth’s climate.

Recent proposals to expand logging, mine metals and drill for natural gas in the forest worry scientists and nature-lovers. In a troubling sign, researchers have documented serious population drops in 13 bird species in drained wetlands and heavily logged areas. Environmentalists are working to expand restrictions on industry in the mostly government-owned boreal forest, less than 10 percent of which is currently off-limits.

“Protecting the integrity of the boreal region over the long term is key to the sustainability and well-being of communities that rely on it,” the Boreal Leadership Council has said. The consortium of First Nations groups, conservation organizations and energy and paper companies is lobbying governments to designate half the boreal as protected.

One organizer of the art trek was Stephen Loring, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian’s Artic Studies Center, who has long been working with local Innu people and looking for evidence of human cultures tens of thousands of years old. “People have always been a part of the boreal landscape,” he says. More than 600 Native communities still live there.

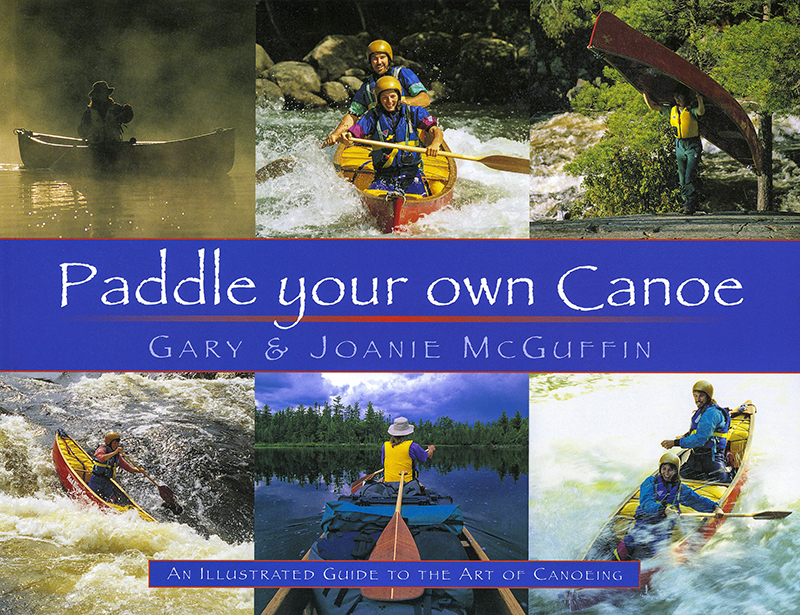

The expedition started at Indian House Lake, then headed north up the George River – or, rather, down the river, which runs north near the Labrador border to where the boreal’s treed landscape meets the tundra. The artist slept in 20-degree weather and woke to snow on several mornings, says Robert Mullen, a Vermont artist who helped organize the venture. But the expedition was “not a macho canoe trip,” he says.

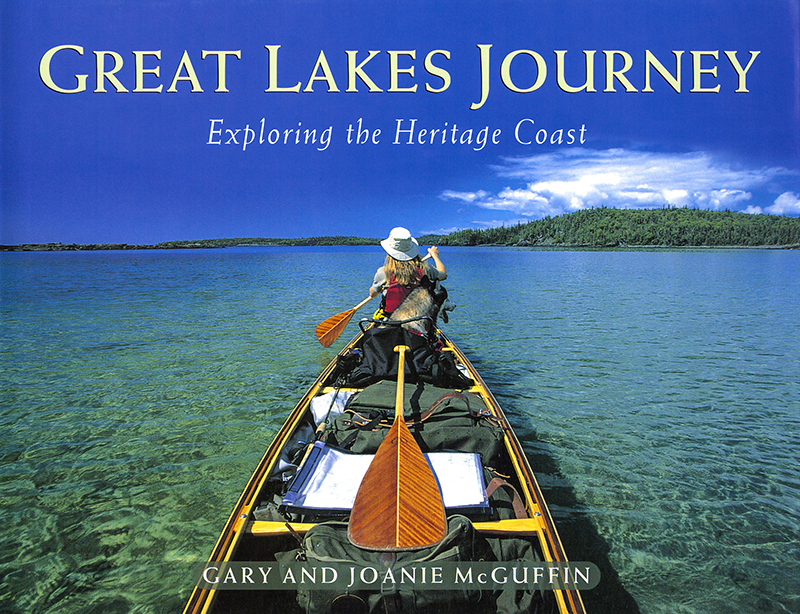

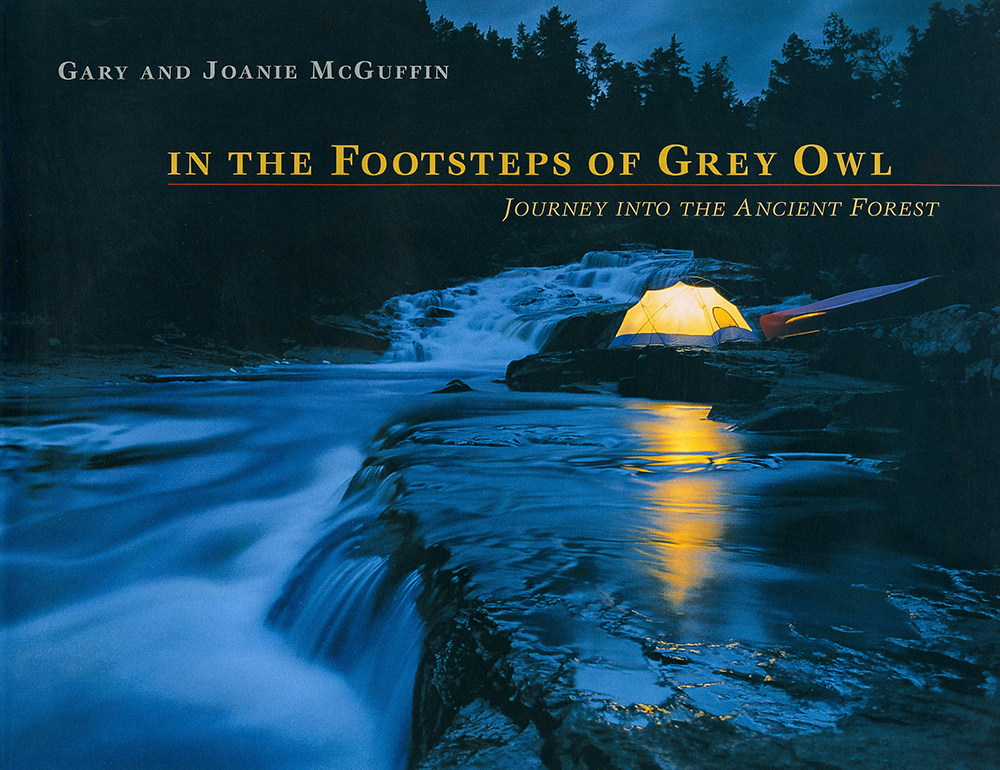

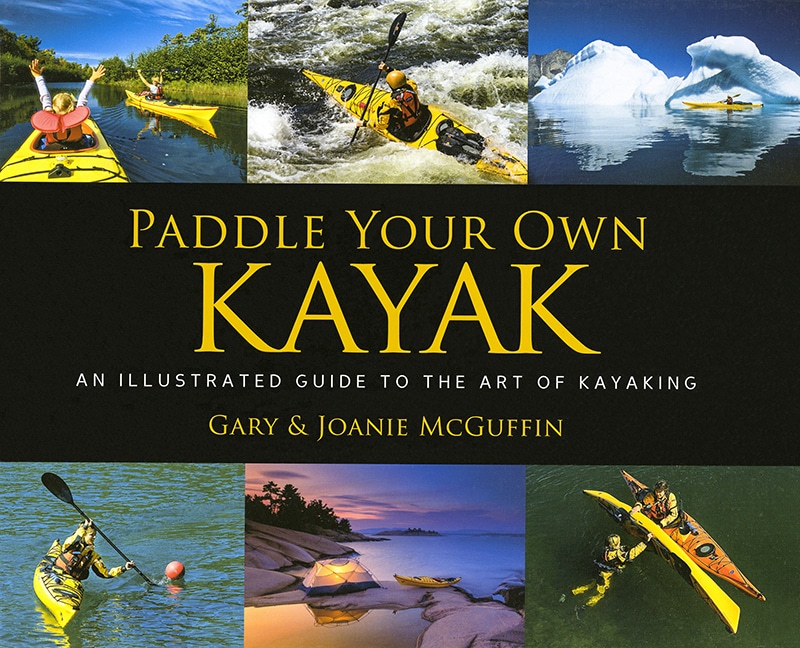

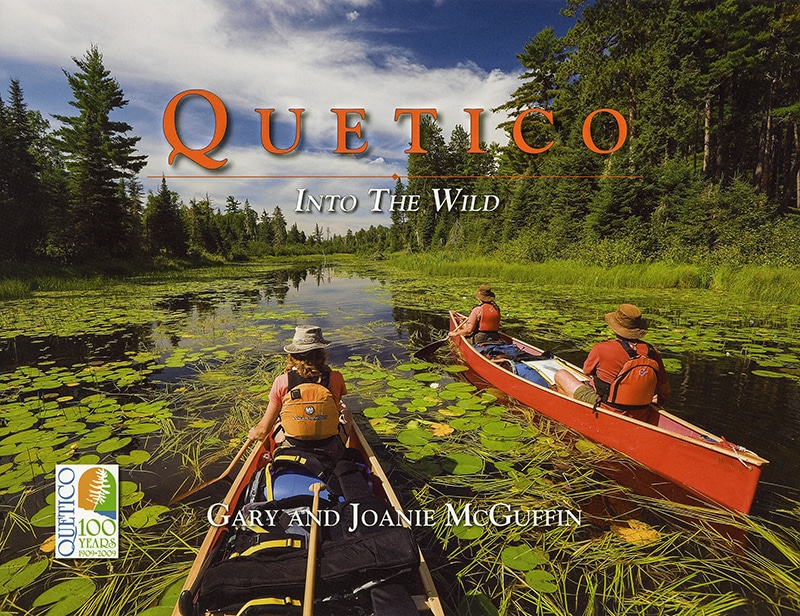

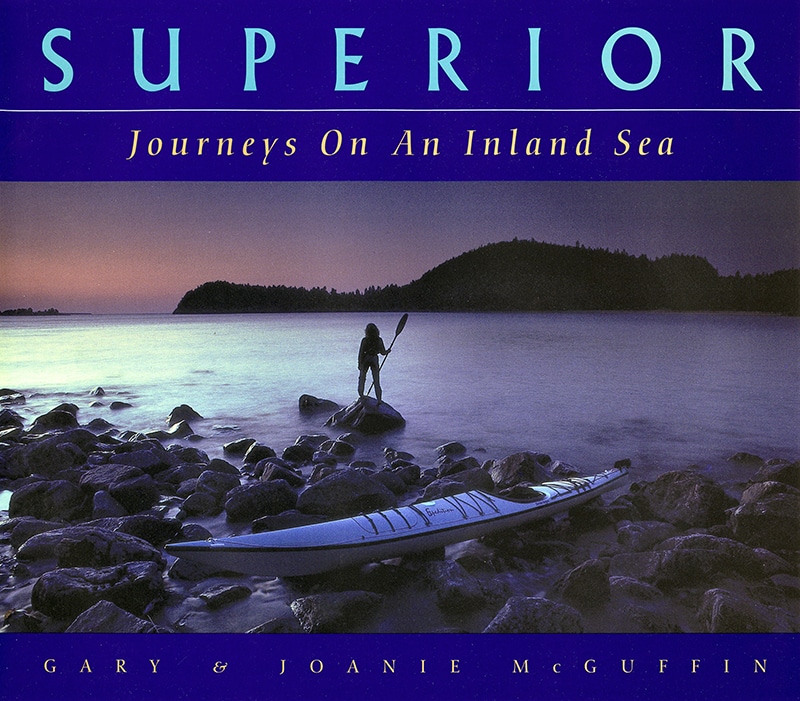

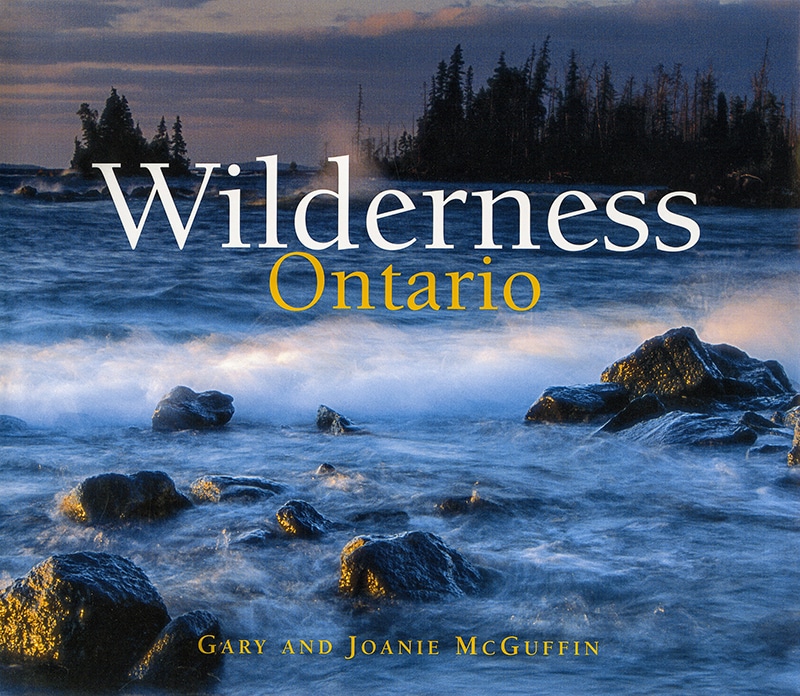

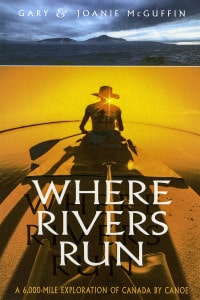

Most boreal animals have never seen people. “You get animals that just don’t know what you are,” says Mullen. During the trip, a short-tailed weasel ran up to him, sniffed his leg and ran across his foot. Mullen and two others were hiking when they saw a small herd of caribou, animals known regionally as gray ghosts because they are shy and blend into the forest. “Be like a caribou!” photographer Joanie McGuffin said, and put her arms in the air like antlers. The others mimicked her – and the animals moved in all around them, affording rare close-up views.

The 76-year-old artist Robert Bate – man, celebrated for his animal portraits and more than a dozen books about nature, spent a day with the group, sketching and gathering ideas for a caribou painting. He says the expanses of tundra, with their low mosaics of ground cover and clumps of spruce and tamarack, offer extraordinary wide-open sense to sketch.

Loring says an exhibition of boreal forest artworks, featuring sketches, photographs and paintings from this past fall’s expedition, will open at the National Museum of Natural History in 2008. Bateman is encouraged. “We need to focus public attention on the top end of the boreal forest,” he says, “because it’s completely forgotten.