IT’S LONELY OUT THERE ON THE ICE ROAD

You met them on their honeymoon – canoeing across Canada. Now the intrepid McGuffins are cycling from coast to coast.

By Joanie McGuffin

Article in The Toronto Star, June 1986

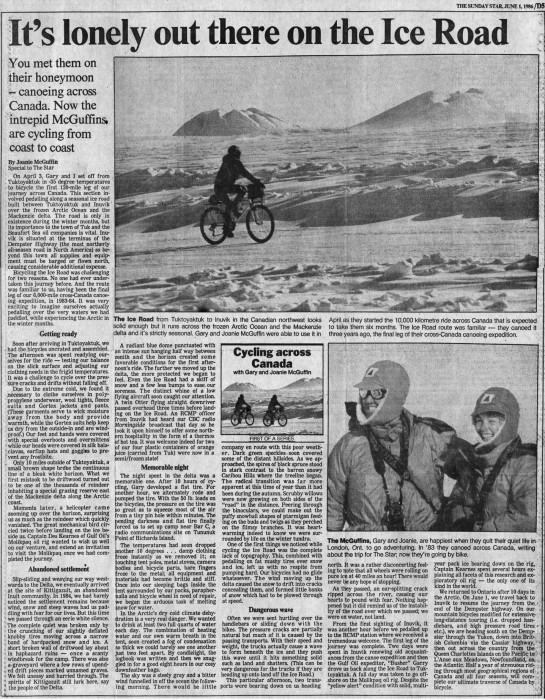

On April 3, Gary and I set off from Tuktoyaktuk in -35 degree temperatures to bicycle the first 120-mile leg of our journey across Canada. This section involved pedalling along a seasonal ice road built between Tuktoyaktuk and Inuvik over the frozen Arctic Ocean and the Mackenzie delta. The road is only in existence during the winter months, but its importance to the town of Tuk and the Beaufort Sea oil companies is vital. Inuvik is situated at the terminus of the Dempster Highway (the most northerly all-season road in North America) so beyond this town all supplies and equipment must be barged or flown north, causing considerable additional expense.

Bicycling the Ice Road was challenging for two reasons. No one had ever undertaken this journey before. And the route was familiar to us, having been the final leg of our 6,000-mile cross-Canada canoeing expedition, in 1983-84. It was very exciting to imagine ourselves actually pedalling over the very waters we had paddled, while experiencing the Arctic in the winter months.

GETTING READY

Soon after arriving in Tuktoyaktuk, we had the bicycles uncrated and assembled. The afternoon was spent readying ourselves for the ride – testing our balance on the slick surface and adjusting our clothing needs in the frigid temperatures. It was a challenge to cycle over the pressure cracks and drifts without falling off.

Due to the extreme cold, we found it necessary to clothe ourselves in polypropylene underwear, wool tights, fleece suits and Gortex jackets and pants. (These garments serve to wick moisture away from the body and provide warmth, while the Gortex suits help keep us dry from the outside-in and are windproof.) Our feet and hands were covered with special overboots and overmittens while our heads were covered in silk balaclavas, earflap hats and goggles to prevent any frostbite.

Only 10 miles outside of Tuktoyaktuk, a small brown shape broke the continuous line of bleak white horizon. What we first mistook to be driftwood turned out to be one of the thousands of reindeer inhabiting a special grazing reserve east of the Mackenzie delta along the Arctic coast.

Moments later, a helicopter came zooming up over the horizon, surprising us as much as the reindeer which quickly vanished. The great mechanical bird circled twice before landing on the ice beside us. Captain Des Kearnes of Gulf Oil’s Molikpaq oil rig wanted to wish us well on our venture, and extend an invitation to visit the Molikpaq once we had completed the journey.

ABANDONED SETTLEMENT

Slip-sliding and weaving our way westwards to the Delta, we eventually arrived at the site of Kittigazuit, an abandoned Inuit community. In 1984, we had barely noticed the settlement remains because wind, snow and steep waves had us paddling with fear for our lives. But this time we passed through an eerie white silence. The complete quiet was broken only be the crunching of our slightly deflated knobby tires moving across a narrow band of hardpacked snow and ice. A short broken wall of driftwood lay about in haphazard ruins – once a scanty windbreak for the camp. There was also a graveyard where a few rows of upended drift pieces marked unnamed graves. We felt uneasy and hurried through. The spirits of Kittigazuit still lurk here, say the people of the Delta.

A radiant blue dome punctuated with an intense sun hanging half way between zenith and the horizon created some favorable conditions for the first afternoon’s ride. The further we moved up the delta, the more protected we began to feel. Even the Ice Road had a skiff of snow and a few less bumps to ease our soreness. The distinct whine of a low flying aircraft soon caught our attention. A twin Otter flying straight downriver passed overhead three times before landing on the Ice Road. An RCMP officer from Inuvik had heard our CBC radio Morningside broadcast that day so he took it upon himself to offer some northern hospitality in the form of a thermos of hot tea. It was welcome indeed for two of our four plastic containers of orange juice (carried from Tuk) were now in a semi/frozen state!

MEMORABLE NIGHT

The night spent in the delta was a memorable one. After 10 hours of cycling, Gary developed a flat tire. For another hour, we alternately rode and pumped the tire. With the 50 lb. loads on the bicycles, the pressure on the tire was so great as to squeeze most of the air from a tiny pin hole within minutes. The pending darkness and flat tire finally forced us to set up camp near Bar C, a radio communications site on Tununuk Point of Richards Island.

The temperatures had soon dropped another 10 degrees… damp clothing froze instantly as we removed it; on touching tent poles, metal stoves, camera bodies and bicycle parts, bare fingers froze to the metal; all equipment and materials had become brittle and stiff. Once into our sleeping bags inside the tent surrounded by our packs paraphernalia and bicycle wheel in need of repair, we began the arduous task of melting snow for water.

In the Arctic’s dry cold climate dehydration is very real danger. We wanted to drink at least two full quarts of water each day. The combination of heating water and our own warm breath in the tent, soon created a fog of condensation so thick we could barely see one another just two feet apart. By candlelight, the logbook was written and then we snuggled in for a good eight hours in our cosy downfeather bags.

The sky was a steely gray and a bitter wind funnelled in off the ocean the following morning. There would be little company en route with this poor weather. Dark green speckles soon covered some of the distant hillsides. As we approached, the spires of black spruce stood in stark contrast to the barren snowy Caribou Hills where the treeline began. The radical transition was far more apparent at this time of year than it had been during the autumn. Scrubby willows were now growing on both sides of the “road” in the distance. Peering through the binoculars, we could make out the puffy snowball shapes of ptarmigan feeding on the buds and twigs as they perched on the flimsy branches. It was heart-warming indeed to know we were surrounded by life on the winter tundra.

One of the first things we noticed while cycling the Ice Road was the complete lack of topography. This combined with pedalling on fat mushy tires over snow and ice, left us with no respite from pumping hard. Our bicycles had no glide whatsoever. The wind moving up the delta caused the snow to drift into cracks concealing them, and formed little banks of snow which had to be plowed through at speed.

DANGEROUS WAVE

Often we were sent hurtling over the handlebars or sliding down with the bikes. The pressure cracks are partially natural but much of it is caused by the passing transports. With their speed and weight, the trucks actually cause a wave to form beneath the ice and they push this wave until it hits something solid such as land and shatters. (This can be very dangerous for the trucks if they are heading up onto land off the Ice Road.)

This particular afternoon, two transports were bearing down on us heading north. It was a rather disconcerting feeling to note that all wheels were rolling on pure ice at 40 miles an hour! There would never be any hope of stopping.

As they passed, an ear-splitting crack ripped across the river, causing our hearts to pound with fear. Nothing happened but it did remind us that the instability of the road over which we passed; we were on water, not land.

From the first sighting of Inuvik, it was another hour before we pedalled up to the RCMP station where re received a tremendous welcome. The first leg of the journey was complete. Two days were spent in Inuvik renewing old acquaintances from the canoe expedition and then the Gulf Oil expeditor, “Busher” Garry drove us back along the Ice Road to Tuktoyaktuk. A full day was taken to go offshore on the Molikpaq oil rig. Despite the “yellow alert” condition with solid, multiyear pack ice bearing down on the rig, Captain Kearnes spent several hours explaining all facets of this research and exploratory oil rig – the only one of its kind in the world. We returned to Ontario after 10 days in the Arctic. On June 1, we travel back to Inuvik to resume the journey from the end of the Dempster highway. On our mountain bicycles modified for extensive long-distance touring (i.e. dropped handlebars, and high pressure road tires etc.), we are heading south on the Dempster through the Yukon, down into British Columbia via the Cassiar highway, then out across the country from the Queen Charlottes Islands on the Pacific to L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, on the Atlantic. Half a year of strenuous riding through most geographical regions of Canada and all four seasons, will complete our ultimate traverse of Canada by bicycle.

A Couple’s Cross-Canada 5 month Cycling Odyssey

By Joanie McGuffin

Article in The Toronto Star, December 1986

Twelve hours after cycling into L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, a snowstorm swept across the northern peninsula.

We had finished our journey in time, five months and 7,500 miles (12,500 km) after we started.

It had taken three days to follow the northern peninsula road to the terminus of our cross-Canada adventure. We tracked through light snow near Cornerbrook, “where it rained most of the time, and the cutting wind blasted off the ocean so strongly that it kept pushing us off the roadway.

During the final days we were forced to endure the most difficult weather of the entire trek.

A flat tire forced me to walk the final three kilometres in my stiff-soled cycling shoes to camp at Pinchgut Lake, after an already difficult day of pedalling. That night the rain beat continuously against the tent and collected on the clay ground beneath the floor. Slowly it filled with cold water as we huddled together, shivering in our soggy sleeping bags.

In the span of five months, Gary and I had touched three oceans. We survived severe weather, treacherous mountain trails, crowding log hauler trucks and unexpected wildlife visitations.

Our most memorable hinterland guest arrived after 2 a.m. one night. A rough scraping against the zipper of the tent disrupted our slumber. Gary unzipped the door and peered through the darkness with the aid of a flashlight beam. Suddenly a huge head turned and the glowing eyes of an enormous black bear met ours. The power and speed with which the bear retreated left us with the sobering realization that there wasn’t a bear anywhere that couldn’t outrun us on our bicycles.

Moments after our impromptu meeting, we scrambled from the tent saddlebags packed and ample incentive to find a new campsite. This wasn’t the first time we had made an unexpected move, in the middle of the night, or the last during our long crossing.

We began our adventure from the Inuit village of Tuktoyaktuk on the frozen Beaufort Sea. We cycled south to the Queen Charlotte Islands on the Pacific coast, then across Canada along a northerly route eventually ending at L’Anse aux Meadows on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. The route was mapped to include both territories and all 10 provinces, as well as major islands and most of Canada’s geographical regions.

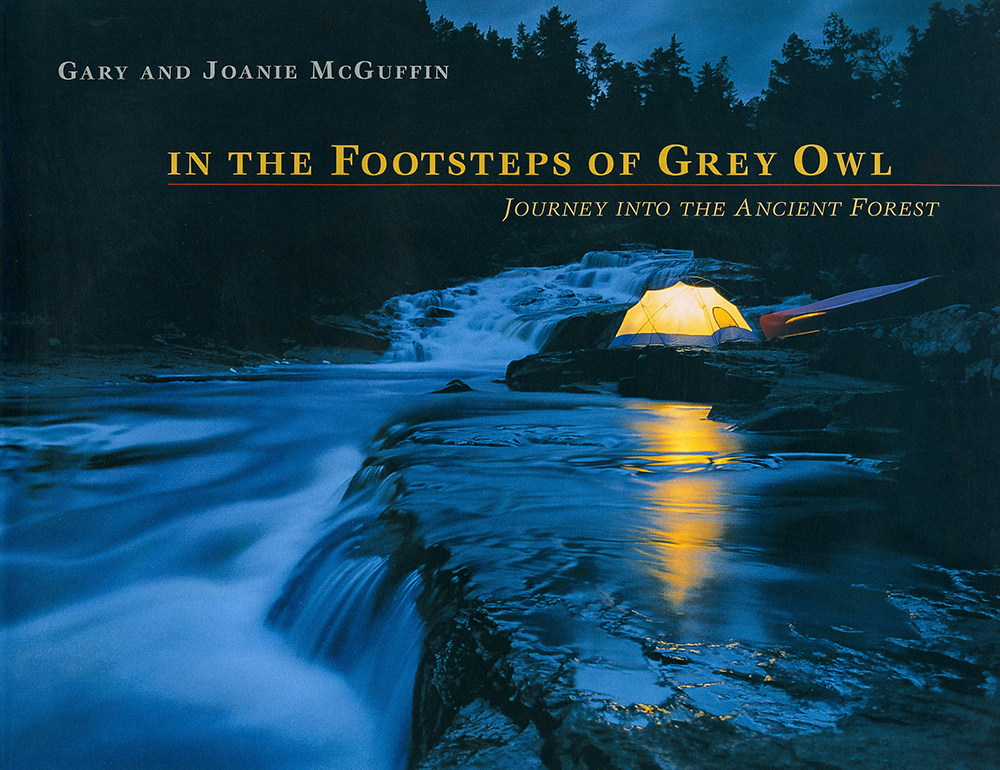

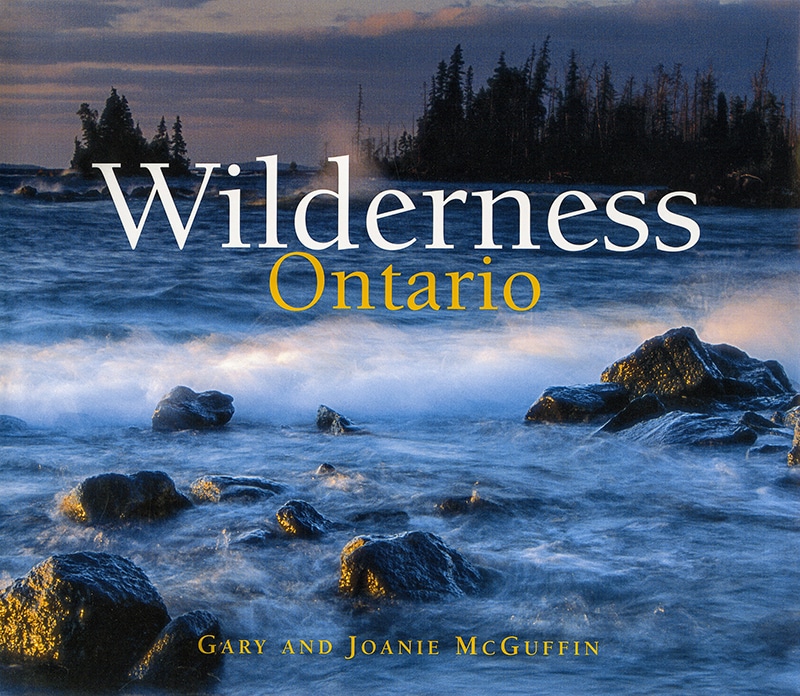

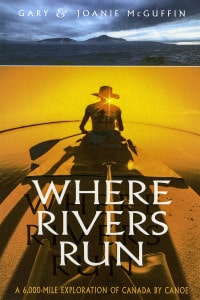

In 1983 Gary and I crossed the country by canoe. Both adventures presented certain obvious dangers and offered particular challenges, some that we were prepared to handle, others were unexpected. We survived. In our estimation, we were richly rewarded for our efforts, physically and emotionally. Most inspiring of all, we completed a dream.

Last April 3 dawned crystal clear. The thermometer registered minus 40C. Sweeping out across the stark white landscape was a thin black ribbon known as the Ice Road.

As far as we knew, or any of the local people recollected, no one had ever attempted to bicycle between Tuktoyaktuk and Inuvik. In September, 1984, this same 190 kilometres had marked the last stretch of our 6,000-mile (9,650-km) canoe expedition which began in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Since our route by water had, with season’s change, become a road of ice we deemed it an appropriate beginning to our cycling adventure across Canada.

For two bitterly cold days, we slithered our way along the slick ice surface feeling, at times, utterly alone.

Occasionally we encountered comforting signs of life such as fresh tracks of the Arctic fox and flocks of ptarmigan feeding on the buds of scrub willows. East of the delta a caribou lifted his head in curiosity and quietly watched us pass.

WAITING FOR THAW

Upon reaching Inuvik, we were forced to wait for the spring thaw. Since Inuvik marks the northern terminus of the Dempster Highway, it was no longer necessary to rely on the firm ice conditions for travel. With the arrival of June came a late spring blizzard and the rivers were kept locked with ice. The road is bisected by two major river systems within the first 320 kilometres; the Mackenzie and the Peel. During autumn freeze-up and spring thaw, this section of road is closed to through travellers.

Our schedule was being seriously threatened. Would we be able to leave in time to reach Newfoundland before winter?

Finally, on June 18, the ferries began operation and we were able to pedal on our way. We were miles north of the Arctic Circle and experiencing never-ending daylight. We began to lose all sense of time and days.

For a cyclist, the Dempsters hazards include isolation, sudden and severe weather changes, high winds and varying road surfaces. Both our bicycles and our bodies were subjected to bone-jarring cracks and crevices, slipping and grinding through thick gravel, razor-sharp shale, boulders and sand.

For almost all of the journey’s first 2,400 kilometres to Meziadin Junction, in central British Columbia, we had followed unpaved roads.

ROAD A QUAGMIRE

Rainy days on the Stewart-Cassiar highway transformed the road surface into a quagmire. The billowing clouds of dust turned to a fog of moist clay and settled on our bodies until we looked like a couple of plaster dolls. At the end of such days we rode our loaded bicycles straight into the nearest river.

After leaving the green and peaceful Queen Charlottes, it didn’t seem to take much time actually pedalling through the Rockies. Before long the Yellowhead Pass and Jasper were behind us. The layer of mountains were peeling away to reveal the Alberta foothills.

From Edmonton we chose a northerly route through Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. It was a round-about journey travelling through such towns as Cold Lake, Meadow Lake, Prince Albert and The Pas. A few lakes, river and hills broke up the endless vista of prairie farmlands.

August was harvesting month and as far as the eye could see the fields rippled in a flag of gold, green and brown. Occasionally we cycled past fields of barley and oats flattened by a devastating burst of hail. The westerly winds prevailed in our favor. Our daily miles were averaging 120 (about 190 km) and our longest day over the entire expedition was a 150-mile (240-km) ride through central Manitoba.

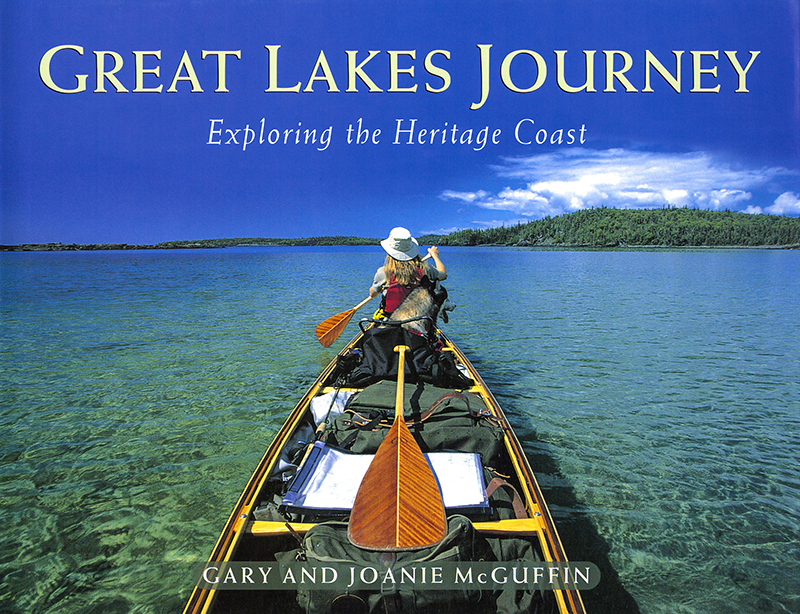

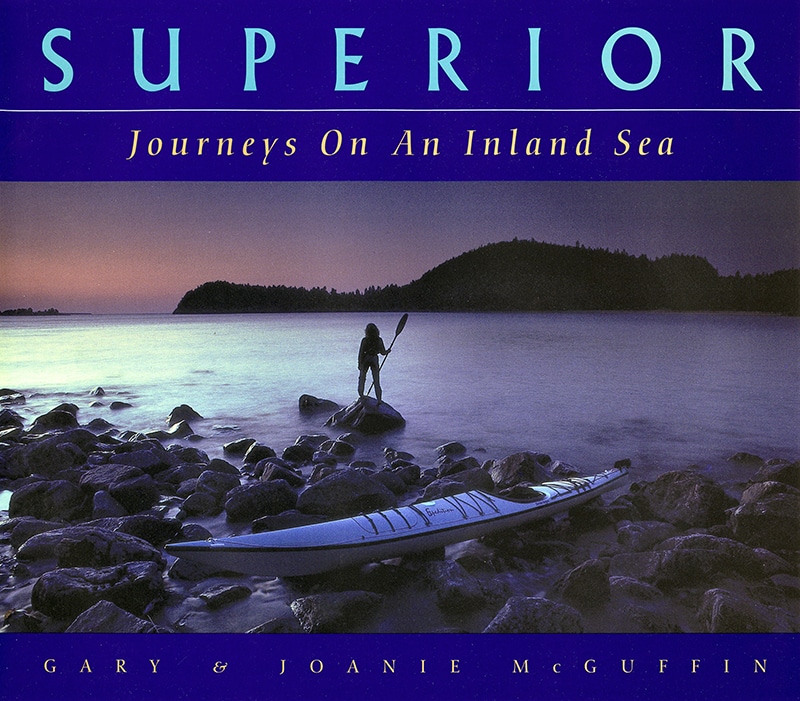

Just three weeks after leaving the foothills of the Rockies, we were back into the hills again. East of Thunder Bay along the northern coast of Lake Superior, there is a road that skirts the largest freshwater body in the world. It is an awesome and majestic coastline that has changed very little since the retreat of the last glacier 10,000 years ago.

On Sept. 5 we crossed the Quebec border. It had taken just one month to traverse the four inland provinces. Now the days were growing much shorter and the weather was turning colder and less predictable.

In an attempt to travel on the most northerly route possible, we were forced to pedal over 300 miles (480 km) northeast of the mining town of Chibougamau. It was a lonely stretch of highway, that seemed at times without end. A few logging trucks rumbled past. We were almost killed when two trucks passed us side-by-side. We were both forced off the road down into the soft shoulder. But as we plunged downward our fat-tired bicycles gripped the terrain and by some miracle allowed us to regain control and get back onto the pavement. For the moment we actually forgot our other miseries, and our shaking wasn’t due this time to the prevailing temperature.

Cycling around the Gaspe on the Gulf of St. Lawrence marked the beginning of the end of our journey. We had reached our third ocean.

ANOTHER OCEAN

The Maritimes followed, then the challenges of Cape Breton and Newfoundland. At North Sydney we caught the 11:30 p.m. ferry to Newfoundland. A cold drizzle prevailed over Port aux Basques as we pulled into the wharf early that morning. We set up camp on the only patch of grass we could find on this barren landscape of rock and waited for morning. We again were greeted by tremendous downpour of rain.

As we rode through the mountains of Gros Morne National Park, the wind at times was so strong that it was practically impossible to stay on the road. On Oct. 29 the overcast sky threatened again as we cycled the final miles into our destination, L’Anse aux Meadows. This 1,000-year-old Viking camp has made its mark in history as the first settlement of white man in North America.

The local people waved to us from their windows as we pedalled past. It appeared they had been expecting us.

As we approached that final hill, watching how magically the low green point of land curved into the ocean, we were graced by the sun breaking through the cloud cover.

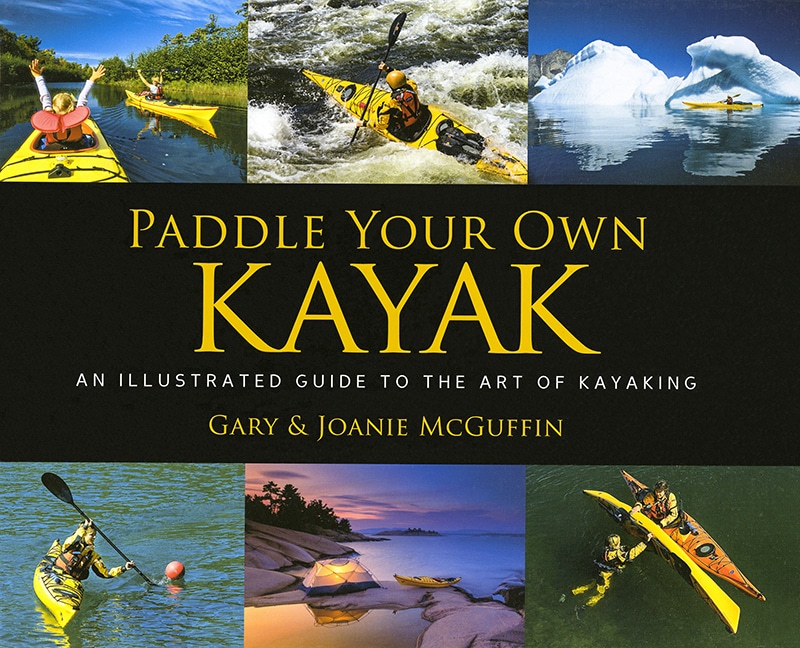

As we stood there we thought of the months of preparation and cycling it had taken to reach this place. Completing this adventure had only given us more momentum to find new and more exciting challenges. Even before we had worked all the cycling kinks out of our travel weary legs, we both agreed sea kayaks would be our next form of self-propelled travel.