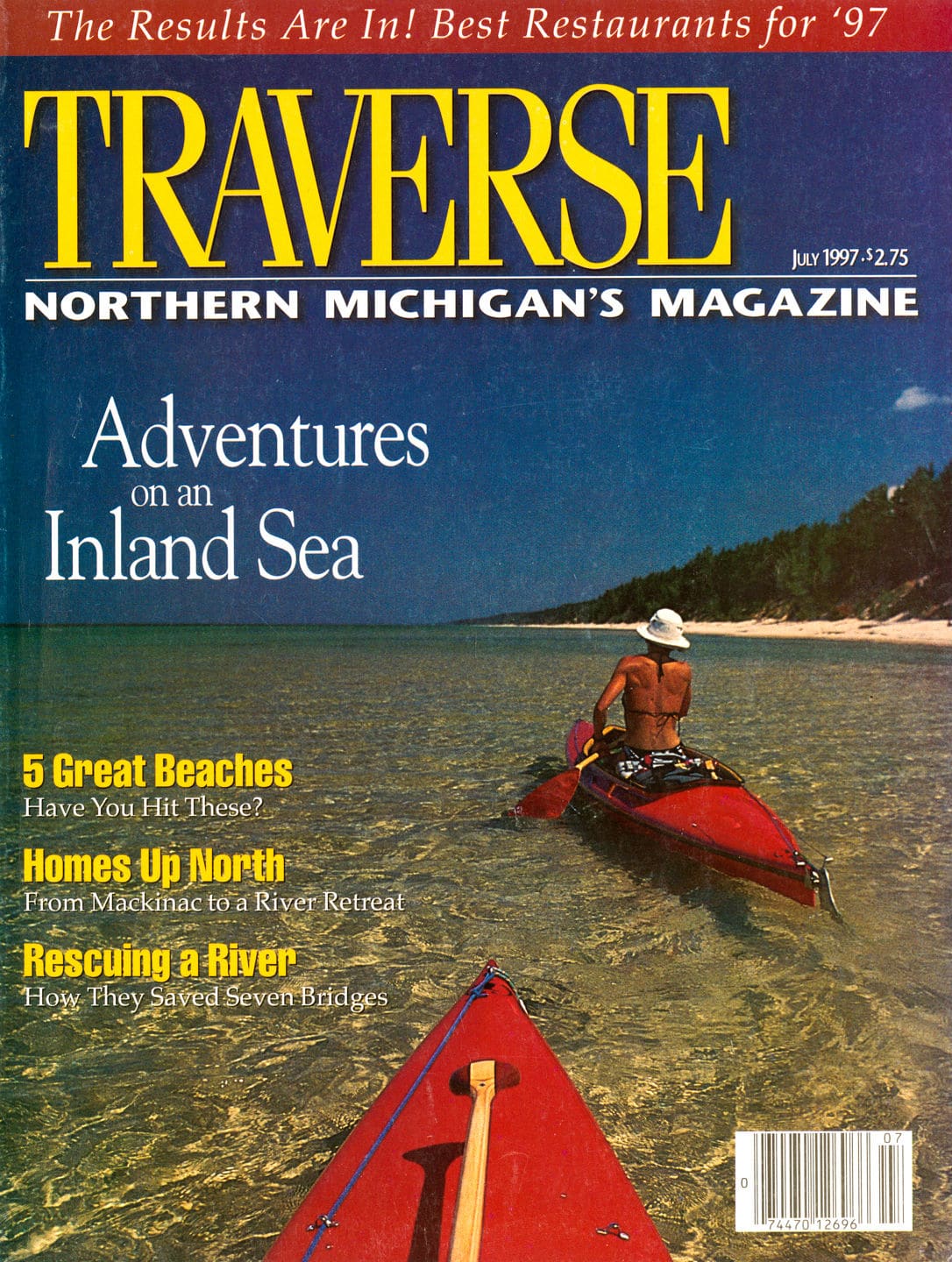

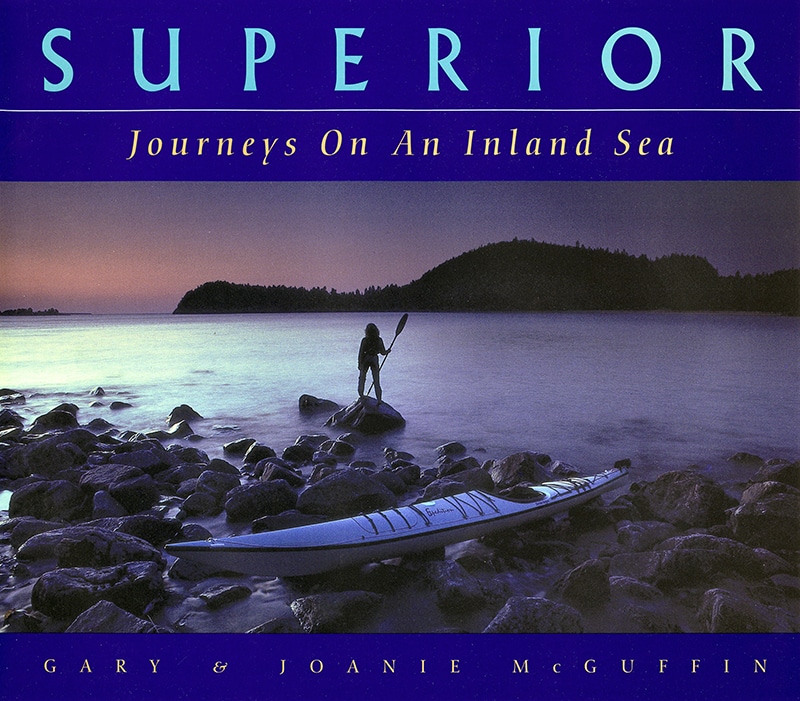

Superior Journeys on an Inland Sea

By Joanie and Gary McGuffin

Article in TRAVERSE, July 1997

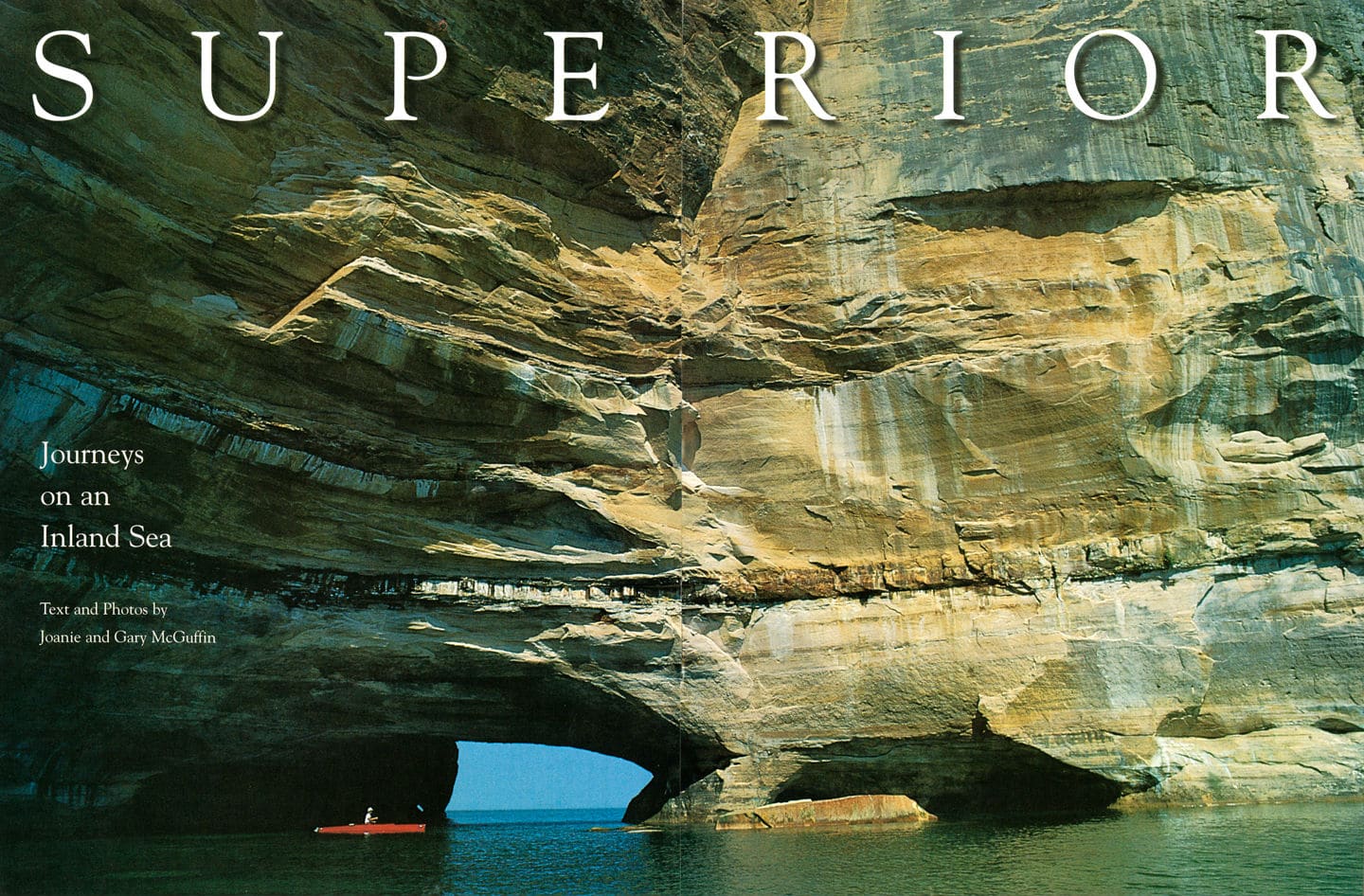

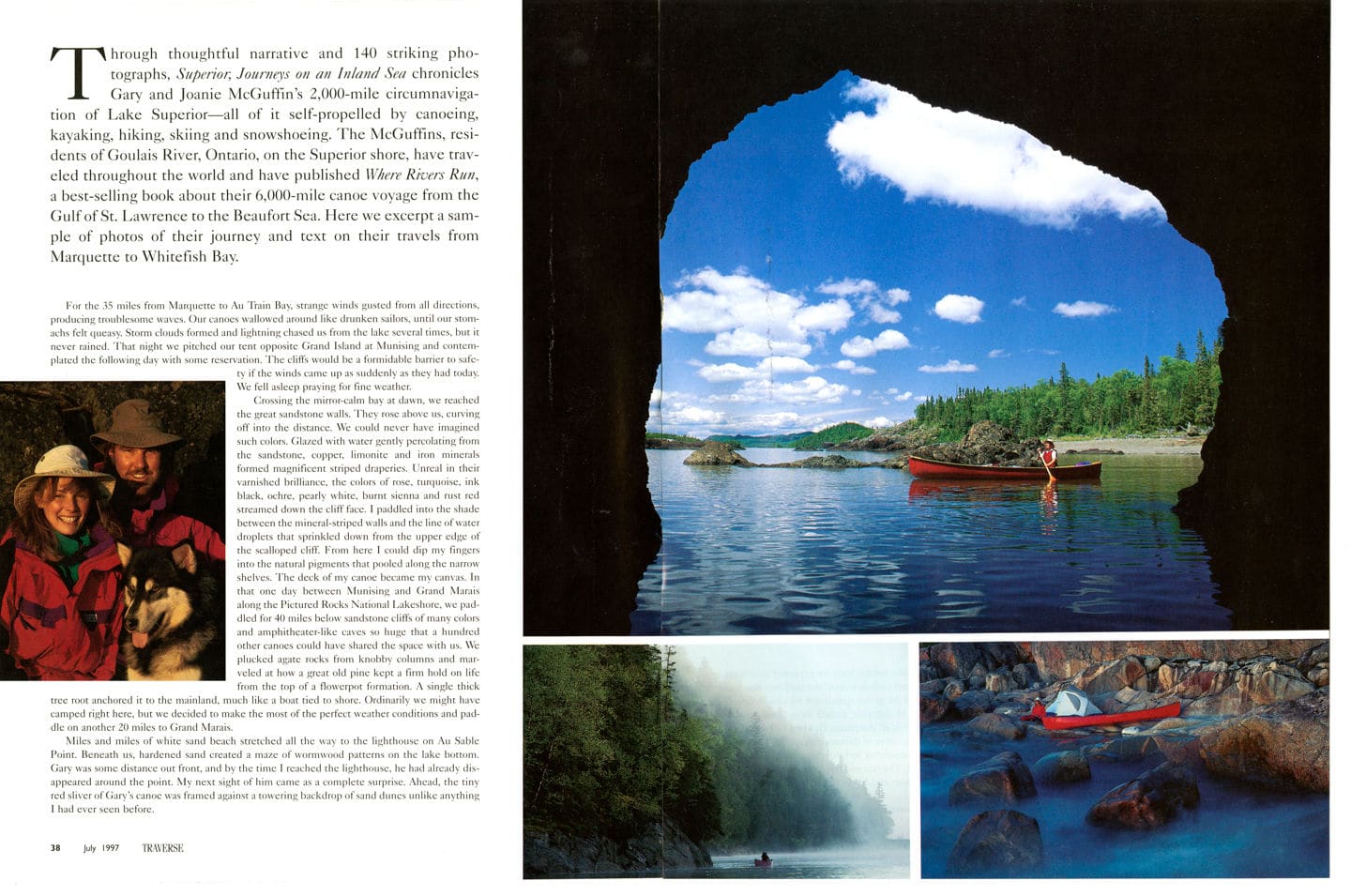

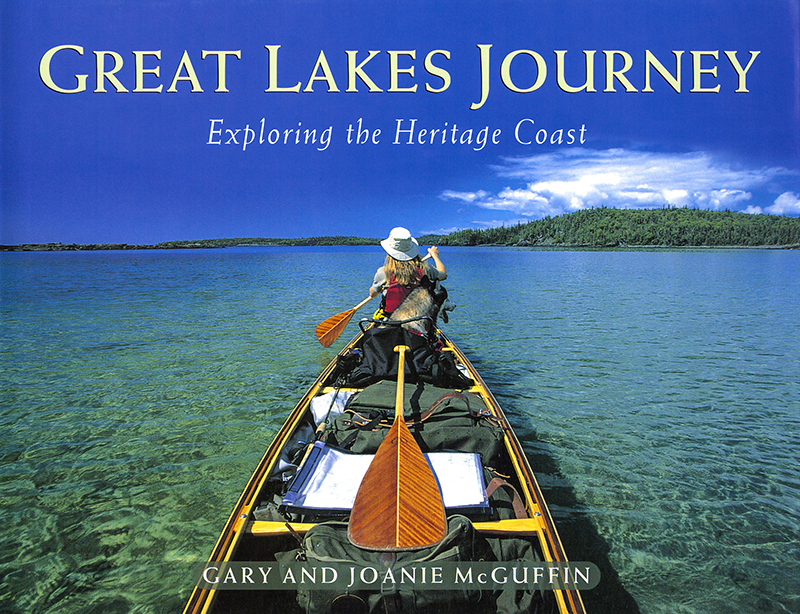

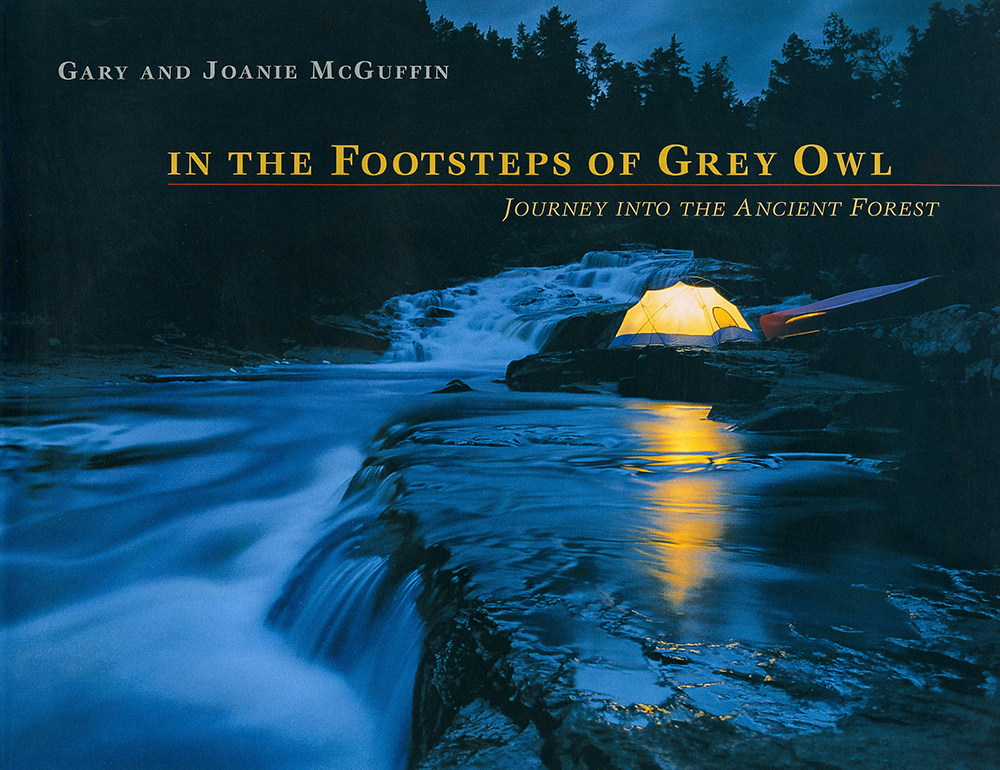

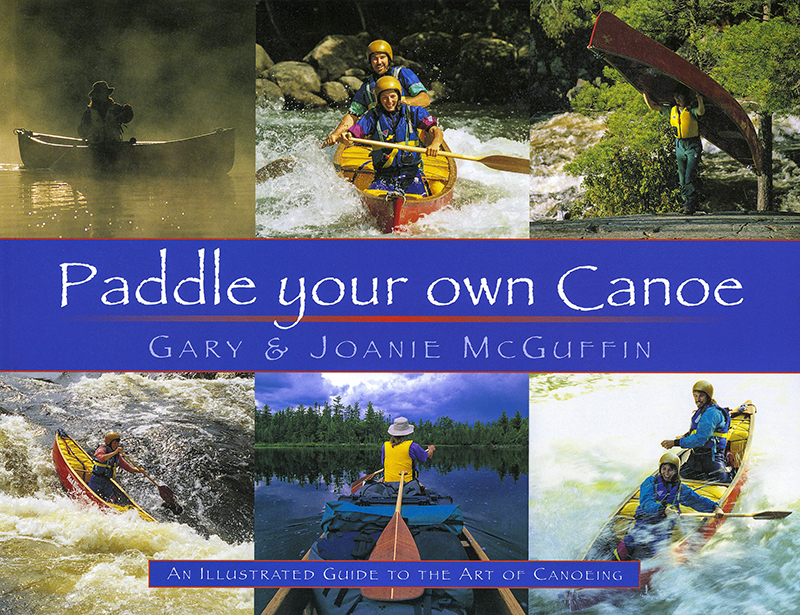

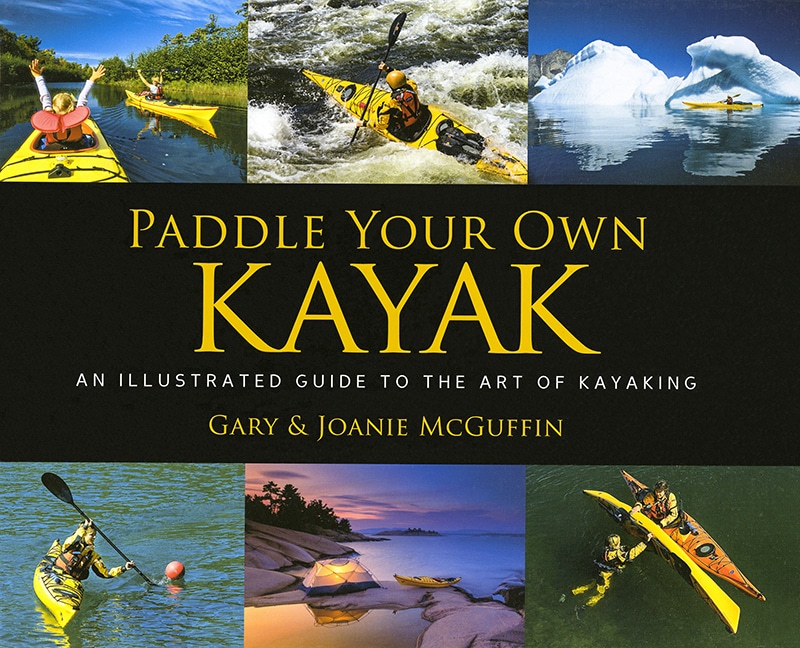

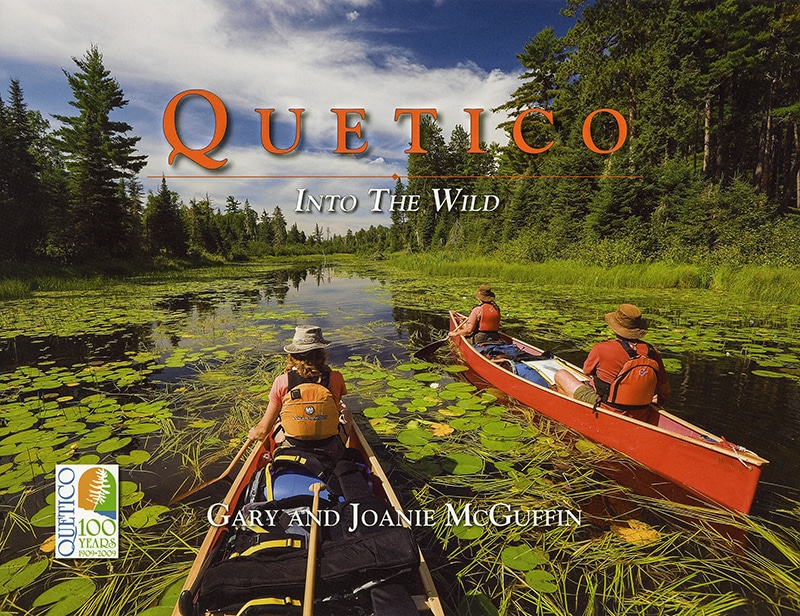

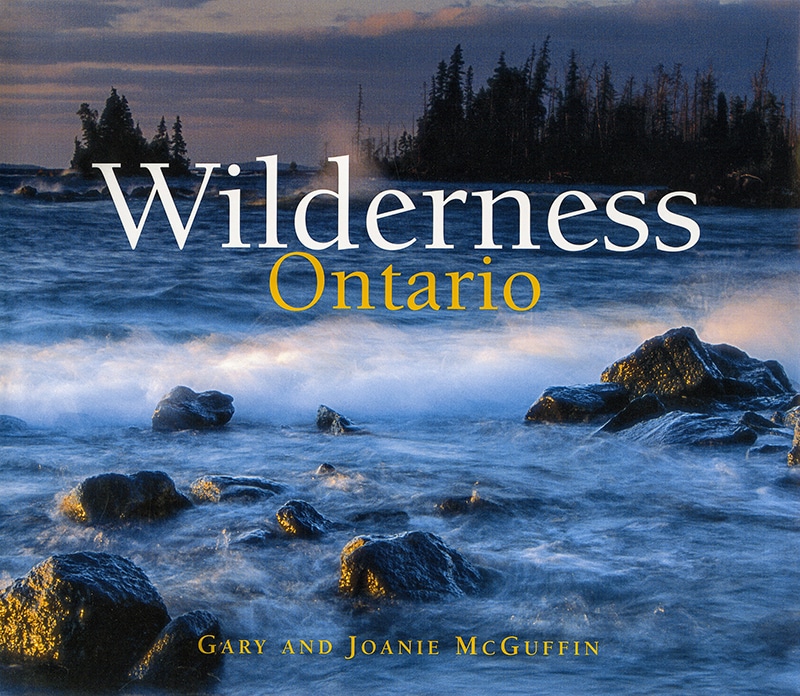

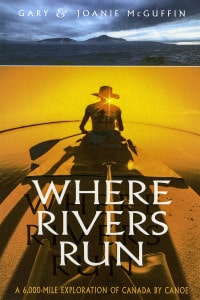

Through thoughtful narrative and 140 striking photographs, Superior, Journeys on an Inland Sea chronicles Gary and Joanie McGuffin’s 2,000-mile circumnavigation of Lake Superior – all of it self-propelled by canoeing, kayaking, hiking, skiing and snowshoeing. The McGuffins, residents of Goulais River, Ontario, on the Superior shore, have traveled throughout the world and have published Where Rivers Run, a best-selling book about their 6,000-mile canoe voyage from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Beaufort Sea. Here we excerpt a sample of photos of their journey and text on their travels from Marquette to Whitefish Bay.

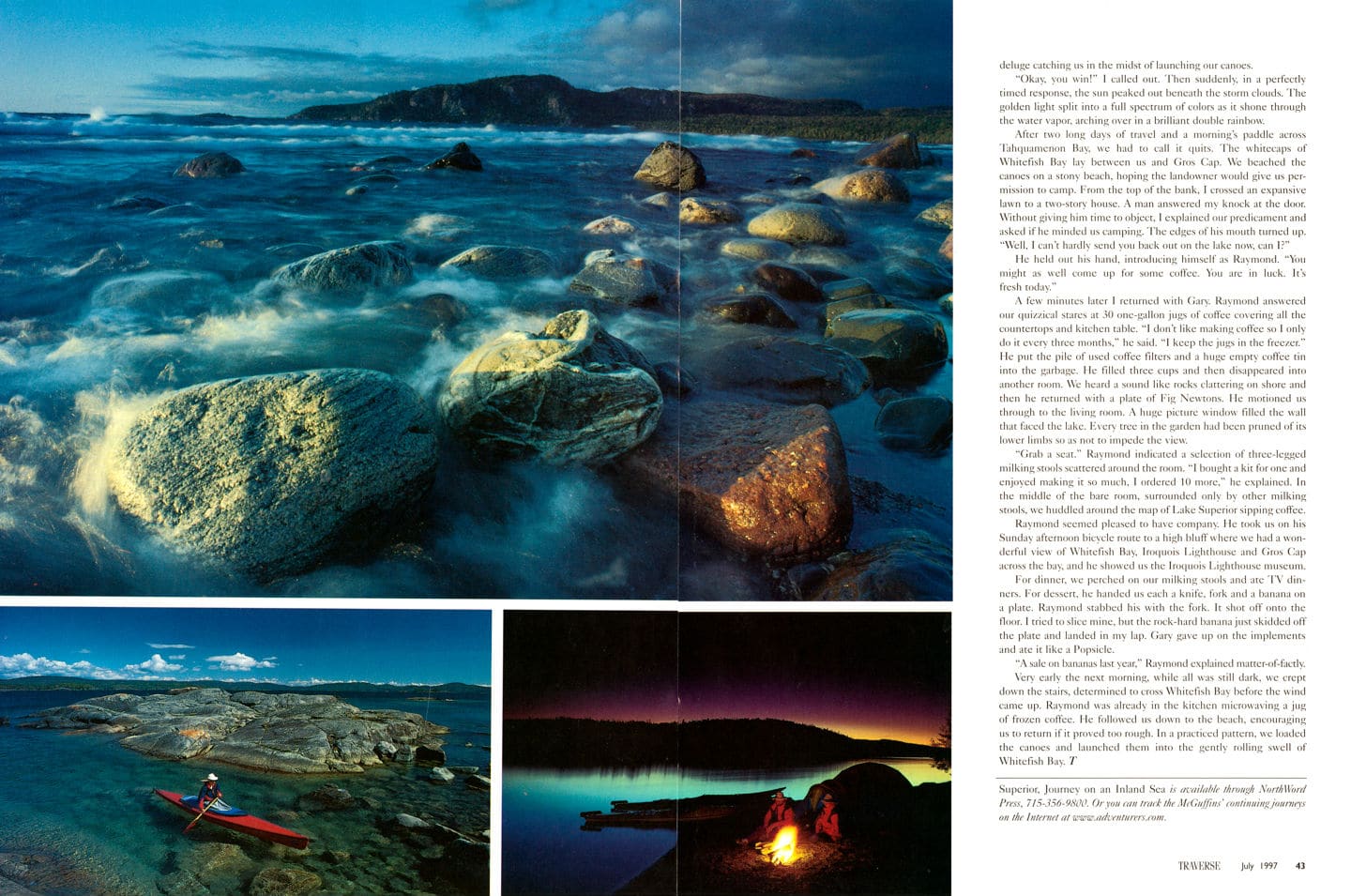

For the 35 miles from Marquette to Au Train Bay, strange winds gusted from all directions producing troublesome waves. Our canoes wallowed around like drunken sailors, until our stomachs felt queasy. Storm clouds formed and lightning chased us from the lake several times but it never rained. That night we pitched our tent opposite Grand Island at Munising and contemplated the following day with some reservation. The cliffs would be a formidable barrier to safety if the winds came up as suddenly as they had today. We fell asleep praying for fine weather.

Crossing the mirror-calm bay at dawn, we reached the great sandstone walls. They rose above us curving off into the distance. We could never have imagined such colors. Glazed with water gently percolating from the sandstone, copper, limonite and iron minerals formed magnificent striped draperies. Unreal in their varnished brilliance, the colors of rose, turquoise, ink black, ochre, pearly white, burnt sienna and rust red streamed down the cliff face. I paddled into the shade between the mineral-striped walls and the line of water droplets that sprinkled down from the upper edge of the scalloped cliff. From here I could dip my fingers into the natural pigments that pooled along the narrow shelves. The deck of my canoe became my canvas. In that one day between Munising and Grand Marais along the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, we paddled for 40 miles below sandstone cliffs of many colors and amphitheater-like caves so huge that a hundred other canoes could have shared the space with us. We plucked agate rocks from knobby columns and marveled at how a great old pine kept a firm hold on life from the top of a flowerpot formation. A single thick three root anchored it to the mainland, much like a boat tied to shore. Ordinarily we might have camped right here, but we decided to make the most of the perfect weather conditions and paddle on another 20 miles to Grand Marais.

Miles and miles of white sand beach stretched all the way to the lighthouse on Au Sable Point. Beneath us hardened sand created a maze of wormwood patterns on the lake bottom. Gary was some distance out front, and by the time I reached the lighthouse, he had already disappeared around the point. My next sight of him came as a complete surprise. Ahead, the tiny red sliver of Gary’s canoe was framed against a towering backdrop of sand dunes unlike anything I had ever seen before.

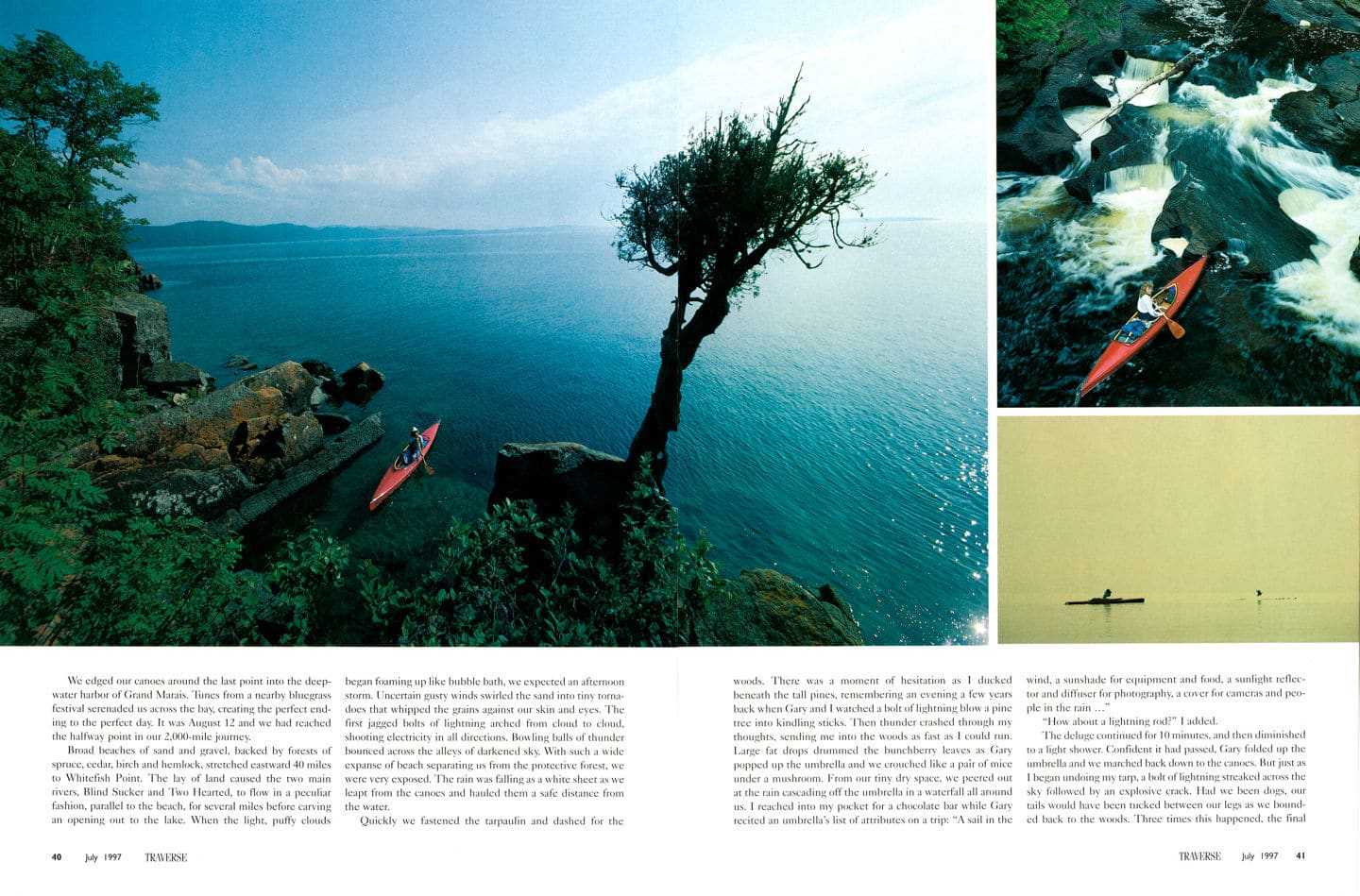

We edged our canoes around the last point into the deep-water harbor of Grand Marais. Tunes from a nearby bluegrass festival serenaded us across the bay, creating the perfect ending to the perfect day. It was August 12 and we had reached the halfway point in our 2,000-mile journey.

Broad beaches of sand and gravel, backed by forests of spruce, cedar, birch and hemlock, stretched eastward 40 miles to Whitefish Point. The lay of land caused the two main river, Blink Sucker and Two Hearted, to flow in a peculiar fashion, parallel to the beach, for several miles before carving an opening out to the lake. When the light, puffy clouds began foaming up like bubble bath, we expected an afternoon storm. Uncertain gusty winds swirled the sand into tiny tornadoes that whipped the grains against our skin and eyes. The first jagged bolts of lightning arched from cloud to cloud, shooting electricity in all directions. Bowling balls of thunder bounced across the alleys of darkened sky. With such a wide expanse of beach separating us from the protective forest, we were very exposed. The rain was falling as a white sheet as we leapt from the canoes and hauled them a safe distance from the water.

Quickly we fastened the tarpaulin and dashed for the woods. There was a moment of hesitation as I ducked beneath the tall pines, remembering an evening a few years back when Gary and I watched a bolt of lightning blow a pine tree into kindling sticks. Then thunder crashed through my thoughts, sending me into the woods as fast as I could run. Large fat drops drummed the bunchberry leaves as Gary popped up the umbrella and we crouched like a pair of mice under a mushroom. From our tiny dry space, we peered out at the rain cascading off the umbrella in a waterfall all around us. I reached into my pocket for a chocolate bar while Gary recited an umbrella’s list of attributes on a trip: “A sail in the wind, a sunshade for equipment and food, a sunlight reflector and diffuser for photography, a cover for cameras and people in the rain…”

“How about a lightning rod?” I added.

The deluge continued for 10 minutes, and then diminished to a light shower. Confident it had passed, Gary folded up the umbrella and we marched back down to the canoes. But just as I began undoing my tarp, a bolt of lightning streaked across the sky followed by an explosive crack. Had we been dogs, our tails would have been tucked between our legs as we bounded back to the woods. Three times this happened, the final deluge catching us in the midst of launching our canoes.

“Okay, you win!” I called out. Then suddenly, in perfectly timed response, the sun peaked out beneath the storm clouds. The golden light split into a full spectrum of colors as it shone through the water vapor, arching over in a brilliant double rainbow.

After two long days of travel and a morning’s paddle across Tahquamenon Bay, we had to call it quits. The whitecaps of Whitefish Bay lay between us and Gros Cap. We beached the canoes on a stony beach, hoping the landowner would give us permission to camp. From the top of the bank, I crossed an expansive lawn to a two-story house. A man answered my knock at the door. Without giving him time to object, I explained our predicament and asked if he minded us camping. The edges of his mouth turned up. “Well, I can’t hardly send you back out on the lake now can I?”

He held out his hand introducing himself as Raymond. “You might as well come up for some coffee. You are in luck. It’ fresh today.”

A few minutes later I returned with Gary, Raymond answered our quizzical stares at 30 one-gallon jugs of coffee covering all the countertops and kitchen table. I don’t like making coffee so I only do it every three months,” he said. “I keep the jugs in the freezer.” He put the pile of used coffee filters and huge empty coffee tin into the garbage. He filled three cups and then disappeared into another room. We heard a sound like rocks clattering on shore and then he returned with a plate of Fig Newtons. He motioned us through to the living room. A huge picture window filled the wall that faced the lake. Every tree in the garden had been pruned of its lower limbs so as not to impede the view.

“Grab a sea.” Raymond indicated a selection of three-legged milking stools scattered around the room. “I bought a kit for one and enjoyed making it so much, I ordered 10 more,” he explained. In the middle of the bare room, surrounded only by other milking stools, we huddled around the map of Lake Superior sipping coffee.

Raymond seemed pleased to have company. He took us on his Sunday afternoon bicycle route to a high bluff where we had a wonderful view of Whitefish Bay, Iroquois Lighthouse and Gros Cap across the bay, and he showed us the Iroquois Lighthouse museum. For dinner, we perched on our milking stools and are TV dinners. For dessert, he handed us each a knife, fork and a banana on a plate, Raymond stabbed his with the fork. It shot off onto the floor. I tried to slice mine, but the rock-hard banana just skidded off the plate and landed in my lap. Gary gave up on the implements and ate it like a Popsicle.

“A sale on Bananas last year.” Raymond explained matter-of-factly. Very early the next morning, while all was still dark, we crept down the stair, determined to cross Whitefish Bay before the wind came up, Raymond was already in the kitchen microwaving a jug of frozen coffee. He followed us down to the beach, encouraging us to return if it proved too rough. In a practiced pattern, we loaded the canoes and launched them into the gently rolling swell of Whitefish Bay.